‘To me the endgame was no different from the opening moves’ – Glyph1

To understand Percival Everett’s twenty-first novel, Telephone (2021), requires some knowledge of chess. Midway through all three different versions of this novel, the protagonist plays chess with his dying daughter. This particular game takes place inside a chapter that is itself structured using chess notational headings, such as ‘e3 h6.’ The cryptic notation of such headings are likely either to intrigue or to alienate a reader. Yet they also provide a thematic clue to the novel’s narratorial style.

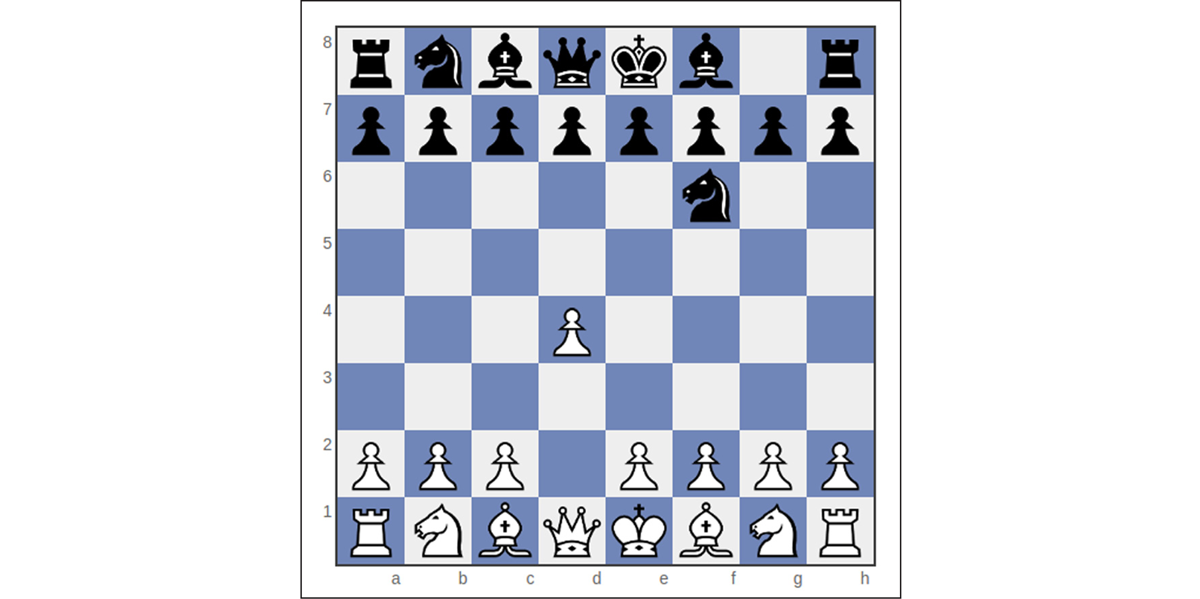

The reader is told, in this match within a match, that ‘Sarah made the first move. d4. I moved my knight. Nf6.’ The result of this opening on the board is shown in Figure 1. In this match, black has modified the Queen’s pawn opening to the Queen’s pawn game variant.2 However, Everett’s narrator also tells the reader that ‘after a couple of moves,’ the following steps on the board are Bh4 and c5.3 Unfortunately, from the position given at the start of this game, these moves are impossible as the bishop cannot access square h4. Thus, the reader is left to surmise the moves between. In this case, the logical and best steps are Bg5 and Ne4; a gambit known as the Trompowsky attack or the Ruth opening.

As the game progresses, the lapses in detail become more significant. Without specifying the number of moves between, the next step given by the text is Bd3 Bxc3. For the white bishop to reach square d3, and then the black bishop to take on c3 (presumably taking the knight) requires several moves in between. As anybody who has studied any level of chess knows, the calculation of the number of moves in between quickly reaches an impossibly large number of permutations. Eventually, Zach resigns to Sarah, the piece of his family that he most wishes to protect, but will, in the endgame, have to lose. As Sarah puts it of her father: ‘you hate to lose pieces’ and ‘you can’t protect everybody’.4 Yet the reader also has to lose the battle of knowing the moves in sequence as it has become untenable, by this point, to calculate what has happened in the gap. The chess match becomes a progressive decline for the reader, marked by moments of elision.

Everett’s chess game is also significant for several other reasons, not least of which is the idea that love can be found in the combative opposition framed by games such as chess. However, first and foremost among these reasons is that the game is synecdochal of the novel’s approach to the idea of close reading and elision. At the beginning of the text, Sarah’s misreading of the board – her missing of a move and a ‘hardly difficult-to-spot bishop’ – leads to an eventual neurological diagnosis.5 Likewise, throughout Everett’s novel, and well beyond the chess game, the reader is asked to fill in the gaps while being given insufficient information fully to reconstruct the narrative events. As these lapses of detail provided in the text mirror Sarah’s seizures, described as moments of ‘taking a tiny nap’ and losing portions of narrative time, Telephone becomes a novel that questions moments of ill communication through narrative elision.6 As a result, I go on here to argue, the true narrative perspective of the text is not, as purported, Zach’s, but Sarah’s, who suffers from Batten disease. Telephone, then, becomes a distributed novel of multiple versions that is playing a chess game against the reader, except that the novel deliberately disables its reader by withholding its moves. Were Telephone a game of chess, we might accuse the novel of cheating.

In addition to this argument about narrative perspective, I will also read the novel as an allegorical broadside against various paradigms of close reading initially pioneered by I.A. Richards that continue to hold significant sway in the academic discipline of literary studies. Despite the pioneering deliberate textual variances that Everett has introduced into the novel and that prompted hoards of Goodreads users to pore over the book’s multiple editions, the basic message of Telephone is perhaps more cynical: how you fill in the missing moves by close reading does not really matter if you reach the same destination regardless.7 Further, I argue that the mechanism by which Telephone achieves this attack on close reading is by innovatively casting the reader as a character with a progressive neurological disorder, thereby disabling the reader and giving them no way to overcome their eventual fate. This yields a progressive stance on disability to Everett’s text that is less patronising than many of the broader societal narratives about disability. However, contrary to his own published statements in which he has claimed that Telephone is an experiment in delegating authority to the reader, the endgame of Everett’s text is for the reader to lose graciously, in the face of the author’s authority through the ability to withhold information.8 In short, I argue in this article that the missing information in Everett’s chess games acts, within a close-reading framework, as a synecdoche for the version variants of the novel, re-aligning the text’s narration with the experience of the character, Sarah, and her progressive disability, which I will argue is best understood through the so-called ‘social model’ of disability.

Such a reading sits well alongside other work that has sought to examine the role of form and narratology in Everett’s texts. For instance, James J. Donaghue notes how the author ‘very consciously manipulates form in his novels to weave together their political and aesthetic purposes.’9 Further, critics such as Zach Linge and Judith Roof have examined Everett’s readerly interplay in terms of ‘hypernarrative,’ a model with an overarching narrator that ‘appeared to decenter both author and reader, meaning and interpretation.’10 In many ways, this paradigm does seem to fit Everett’s own description of his work and the readerly negotiations that are at play. Furthermore, though, Roof describes how the effects of such a narrator in Everett’s novels has a ‘curiously New Critical manner’ in its ‘self-conscious detachment of the telling from the teller and the teller from the fiction of the author’ — a view that sits well with the histories of close reading that I will trace.11 Certainly, the paradigm of a hypernarrator in Telephone, beyond Zach Wells, is a critical concept for the reading that I advance here, and one that is bolstered by the novel’s experimental form, with chess notation and other phrases strewn between the first-person segments.

Finally for this introduction, it is important to note that Everett has played with these ideas of attention over the course of his literary career. For instance, Wounded (2005), one of Everett’s Western novels, traces the boundaries of care and attention in our lives.12 It is a novel in which the protagonist begins by feeling no empathy towards and paying no attention to a kinsman in trouble but ends with a serious act of violence in retribution for the pain of somebody else. Indeed, the opening pages of Wounded are filled with statements of inattention and neglect: ‘why the hell are you telling me?’; ‘ I don’t know you’; ‘you’re not a friend of mine’; ‘you’re barely an acquaintance’; and ‘it’s none of my business’, as just a few examples.13 Yet, in a meta-discursive passage in Wounded, the narrator states that he ‘was also bothered by [his] decided lack of interest,’ highlighting the importance of attention to the text.14 The Trees (2021) – a disturbing and genre-fusing novel that is laugh-out-loud funny even while its subject matter is lynching – likewise features issues of attention and interest as its Heat of the Night-esque parody unfolds.15 Indeed, in the police procedural form that it adopts, The Trees draws attention to what its detective characters can or cannot see at any one point, with this matter of observation applying as much to the history of Emmett Till as to the current crime scene (and, of course, also applying to the narratorial perspective).

Attention – or inattention and lack of care – are also key narratorial themes in Everett’s 2017 novel, So Much Blue. This novel’s narrator, Kevin Pace, and other characters, express their indifference towards the world and almost all aspects of it with alarming and profane frequency. ‘Who cares?’, the narrator asks; ‘I was completely bored by the paintings’, he states; a customs official states that he doesn’t ‘give a flying fuck’; the war criminal, The Bummer, says he doesn’t ‘give half a fuck’; Kevin can’t understand ‘why the fuck [he] was painting,’ in contrast to Leonardo da Vinci, who, we are told, had ‘an insatiable hunger to understand everything around him’.16 The list of uncaring remarks around inattention goes on, symptomatic of the narrator’s stunted emotional/traumatised development: ‘I don’t care’; ‘who the fuck cares?’; ‘I didn’t care’; ‘I didn’t care once I was here’.17 Indeed, So Much Blue is a novel that, like Wounded, seems to focus on a transformation of sites of care/attention, perhaps signalled most poignantly in the sections titled ‘House’ that denote the ‘like’ that Kevin has for his wife, rather than his ‘love,’ which would have been signalled in ‘Home’. A similar phenomenon can also be seen in Everett’s 1999 novel, Glyph, where we are told that ‘apathy […] had a bad reputation’ and that ‘not caring was no mean feat.’18 Hence, while not detracting from the importance of ‘attention’, ‘interest’, and narratorial perspective in Telephone to which I will turn, these foci are part of a longer trajectory in Everett’s oeuvre and should be thus contextualised. As I will now show, placing these themes within a frame of ‘close reading’ can be a profitable way to understand Telephone.

Close Reading and its Discontents

The history of close reading has been well covered elsewhere, but it is worth recapitulating here as its facets are critical to my argument.19 Close reading in literary studies refers to a range of practices that emphasize the importance of paying attention to minute surface differences in a literary work (often at the expense of extra-textual contexts). From our current vantage point, the idea of close reading can seem to be an a-historical and timeless model. It is so ingrained in many university English departments that it can seem like ‘just what literary studies do.’ Usually such practices are, though, now combined with various theoretical and philosophical paradigms as it is not enough to close read texts in isolation from other intellectual and social contexts.

Close reading emerged as a practice in the 1920s with the work of I.A. Richards. As the Arnoldian conception of belles lettres gave way to the formalist New Criticism in the early twentieth century, Richards expressed his belief that ‘unpredictable and miraculous differences’ might be created ‘in the total responses’ to a text from just ‘slight changes in the arrangement of stimuli.’20 In his Practical Criticism of 1930, Richards went on to develop his ideas into an ‘experiment’ or ‘a piece of field-work in comparative ideology’ that concerned the study of how effectively to read detail and discuss literature.21 Then, in his 1942 How to Read a Page, Richards professed his belief that the reader should not be ‘concerned with what as historical fact was going on in the author’s mind when he penned the sentence, but with what the words . . . may mean.’22 This was, at the time, a change of direction that radically altered the historical progression of literary studies and the discipline’s stance towards intentionality.

In recent years, Richards’s model has come under intense scrutiny and, even, attack from a range of quarters. Perhaps the bluntest of these criticisms is simply that Richards’s model is not valid. As Andrew Elfenbein argues, one of the core problems with Richards’s model is that it does not appear to tally with how people actually read; it’s really more of a convenience model, because it allows for a form of reading that can be assessed in a university setting. In Elfenbein’s critique, it could be that Richards’s model is, in reality, merely a ‘fantasy of what would happen […] if a reader had an infinite working memory capacity.’23 This critique is, in other words, to say that readers do not, in reality, drastically re-appraise texts due to minute surface differences of language, mostly because they do not truly notice such changes. This is an important criticism to which I will return with respect to Everett.

Other criticisms of close reading have focused on its ideological and political qualities. Much contemporary close reading is based on the ideas set out by Louis Althusser in Reading Capital (1965). In Althusser’s version of close reading, sometimes called ‘symptomatic reading,’ texts become ideological artifacts with written and unwritten elements (‘sights and oversights’) that can be read. In Althusser’s model, works of fiction can present ‘symptoms’ of the ideological environment in which they were written, usually in the form of textual contradiction. In this schema, Althusser posits ‘the existence of two texts’ with a ‘different text present as a necessary absence in the first.’24 To perform a critical close reading becomes an exercise in showing that the text really says something different to the words on the page as they first appear. This model of critique has proved a powerful method for literary readings because the inherent doctrine is shock, showing the reader that things are not as they seem.

Criticisms of critique stretch back at least thirty years. Stewart Palmer, for instance, suggested in 1989 that we should undertake a ‘critique of these critiques,’ while Cathy N. Davidson and David Theo Goldberg believed in 2004 that it was time that we ‘critiqued the mantra of critique.’25 Likewise, Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus gestured in 2009 towards the political inefficacy of close reading. They write that even though it has ‘become common for literary scholars’ in symptomatic traditions ‘to equate their work with political activism, the disasters and triumphs of the last decade have shown that literary criticism alone is not sufficient to effect change.’26 N. Katherine Hayles was, perhaps, even more blunt: ‘after more than two decades of symptomatic reading . . . many scholars are not finding it a productive practice, perhaps because (like many deconstructive readings) its results have begun to seem formulaic.’27

The strongest outgrowth of criticism of close, critical reading is Rita Felski’s 2015 The Limits of Critique, a work that received a mixed reception.28 For Felski, loosely following Paul Ricœur, critique is a type of ‘hermeneutics of suspicion,’ a phrase that ‘throws fresh light on a diverse range of practices that are often grouped under the rubric of critique: symptomatic reading, ideology critique, Foucauldian historicism, various techniques of scanning texts for signs of transgression or resistance.’ Hence, our reading methods become paranoid, involving ‘vigilance, detachment, and wariness (suspicion)’.29

A variety of counter-models have been proposed. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, for instance, gave us ‘reparative reading,’ while Best and Marcus floated ideas of ‘surface readings.’30 There have also been calls for modes of ‘descriptive criticism’ that orient away from models of critique.31 Nonetheless, at the core of literary studies remains an understandable desire to pay ‘attention to how meaning is produced or conveyed’ and to ask ‘what sorts of literary and rhetorical strategies and techniques are deployed to achieve what the reader takes to be the effects of the work or passage.’32 Close reading has not gone away; it has just mutated. It is at this model, nonetheless, that Everett’s Telephone takes aim.

Phoning it In

Percival Everett, a Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Southern California, has produced, in Telephone, a novel that mounts a critique of close reading as a generalised paradigm. While his previous novels, such as Erasure (2001), have perhaps satirically targeted the academy and the literary marketplace more broadly, Telephone directly sets its sights on literary reading practices.33 As an author of what Mitchum Huehls has called the ‘The Post-Theory Theory Novel,’ we should note that Everett sits among a group of writers who are invested in the strictures of university-level English and its practices; an aspect that comes to the fore, I argue, in Telephone.34

Everett’s primary technique for his critique is the well-known, deliberate version proliferation of the novel.35 Such distributed versioning of the contemporary novel has come to increasing attention in recent years. For instance, I have charted the significantly different versions of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (2000) and the varied editions of Jennifer Egan’s first short-story collection, Emerald City (1993 and 1996).36 Similarly, as just another example, critics have turned to the manuscripts and differences between the published versions of Thomas Pynchon’s novels.37 Likewise, the omnipresent David Foster Wallace (the author, it is claimed, in Telephone, of the ‘most overrated novel’38) has received some textual-scholarly attention.39 While such textual scholarship used to be the exclusive domain of literary history, it is now common to find such methods in the study of contemporary fiction.

Everett’s Telephone, however, takes the study of version variance to a different level. The novel was published by deliberate design in three different editions, with both minor and major differences between each. The versions can be distinguished from one another through attention to the cover art, in which the compass points to a different pole, and to the ISBN formulation, which has been suffixed with either ‘A,’ (Northeast) ‘B,’ (Northwest) or ‘C’ (Southeast). When Brian Rocha asked Everett about the motivations for these variations, Everett claimed that his proposal was to ‘test the limits of a writer’s authority’ and to create a story that is ‘finally constructed by the reader, so there is no single reading of any text.’40 It is my argument here that such a statement is disingenuous given the novel’s testing of inattention as pathology, impairment, and disability (at various points in different ways).

It is, indeed, not easy to see how Everett’s view holds water. Many of the textual variances between the versions of Telephone are insignificantly small and will go unnoticed by most readers. For instance, on page 82 of the novel, the Northeast and Northwest versions give the reader ‘this is what I was thinking about as I placed the chess pieces on the board’ while Southeast reads ‘this is what I was thinking about as I placed the final row of pawns onto the board.’41 This is, of course, a prime example of the type of modified surface to which Richards suggested that we should pay attention. Here we have, precisely, a ‘slight change in the arrangement of stimuli’ that should, if Richards is correct, lead to ‘unpredictable and miraculous differences’ in the ‘total responses’ to a text.

However, the core challenge that Telephone poses to this model is that, fundamentally, most of the central plot elements in the text circle around the notion that we have lapses of concentration and are unable to pay attention. Sarah’s seizures are one such manifestation of this pathology of inattention; that Zach and Meg are equally prone to such lapses is another. For example, the two instances in the text that best embody this are the moments when, looking away for just a second each time, the parents twice lose Sarah. The first, in Paris, occurs when Zach had ‘turned away for only a second.’42 The second, when Sarah slips away into the mountains, happens when ‘no one was looking.’ Yet, the narrator claims, ‘we were always looking, but for one brief moment we each thought the other was looking, and so no one was looking.’43 The novel is full of such lapses of attention that lead to loss. This leads to a reflexive question: how can a reader, then, pay sufficient attention such that minor textual variance will lead to large changes in interpretation? Because, Everett seems to be saying, blink, and you might miss such small changes. And the novel implies that we, as readers, blink far more frequently than we might like to believe, apparently suggesting that it is impossible for readers to pay attention the whole time. As a result, these minor variances are very unlikely to cause the changes in meaning that Richards proposed – and most readers will only read one version of the novel anyway. It is more likely that these changes will go undetected. Unlike in detective fiction, it is possible that the clues will not even be given to the reader.

However, in addition to these minor variances, the novel also contains more significant plot differences between editions. For instance, the scene in Paris where Zach wrestles a pistol from a neo-Nazi occurs only in his imagination in the Northwest edition, whereas in the other two versions it actually happens.44 Indeed, at this point, the Northwest text shifts to pure cerebral interiority: ‘in my mind … in my head …. in my head … in my mind … in my mind …. in my mind I had saved my daughter.’45 Although the rewriting here takes up less than a paragraph, and so in quantitative terms is a minor change, the shift of focus is significant. This is because whether or not Zach is a character who can ‘take action’ is important for our understanding of his later rescue operation in Ciudad Juárez. His heroics in Paris are the character setup piece for his later daring transport operation to bring the enslaved women back to Mexico. If this previous scene has occurred only ‘in his mind,’ the subsequent bravery is less plausible. Hence, at this point, we can begin to see how ‘minor’ changes to the narrative can begin to snowball to the scale of appreciable effects.

As the novel progresses, the changes become more significant. The earlier accidentals give way to more fulsome differences. One of the novel’s pivotal scenes, for instance, is rewritten in Northwest. In the Northeast and Southeast editions, we are given the following version of Zach’s visit to the care home, in which it is implied that he smothers his daughter, Sarah, to death:

I weighed close to two hundred pounds. I had large hands. The thread count of the bedding in Sarah’s room could not have been better than 180. It felt a little scratchy against my palms. The fabric of the pillow slip was not slippery at all. Sarah didn’t move much. She never moved much. She would never again move much, move at all. I told my daughter I loved her. She knew that I loved her.

As I left the building, May gave me a long look, offered a gentle smile.

‘There was a bear outside,’ I said.

‘I saw him,’ she said. ‘Is she sleeping?’

‘She is.’46

By contrast, in Northwest, a new paragraph is introduced in which Zach is interrupted by May and cannot kill Sarah:

May came in while I held the pillow against my child’s face. She didn’t startle or panic but firmly and gently pulled my hands and the pillow away.

Sarah was wide-eyed but unmoving.

I was shaking.

‘I understand,’ she said.

‘I suppose you do.’

‘But I can’t let you do this.’47

The quantitative extent of the change here is, perhaps, no more significant than in the previous, slighter changes. It is not, really, that the new words are massively more numerous than, say, the differences between the epigraphs of the versions: ‘For Henry and Miles’ / ‘For Miles and Henry’ / ‘For my sons.’48 Clearly, though, a lapse of attention at this particular moment – reading only one edition – results in a very different understanding of the novel’s plot arc. It is also the case that most readers of Telephone will only encounter a single version of the novel and will not compare all three. In the case of Telephone, this seems to count as a sloppy reading practice that yields an impoverished understanding of three texts with equal ontological validity. As a result, the significance of the moments at which we lose attention are unevenly distributed in the book. Yet the reader has no way of knowing whether a particular instance is significant or not, in advance.

That said, there is one point in the novel that usually does receive significantly more attention than other parts: the ending.49 In Telephone, one version of the text, Southeast, ends differently from the other two editions. In Northeast and Northwest, Zach manages safely to smuggle the rescued women across the border. However, in Southeast, one of the women, Maribel, is shot by the slavers and the bus breaks down. Instead of making it across the border, they are forced to seek help in an urgent care center, where the health professionals state that they will have to report the gunshot wound to the authorities. As the novel closes, the healthcare worker asks for Maribel’s ‘occupation,’ to which Zach replies ‘Slave.’50 This contrasts with the scenario in Northeast and Northwest where the scene is made more about Zach’s own personal quest for redemption. In these versions, Zach narrates that he ‘would not be able to express to them that [he] was not saving them, but that they were saving [him].’ The text also ends with a flashback to the moment of Sarah’s (near) death, with both these versions citing the appearance of the bear at the window in the smothering scene.51 In Southeast, though, it is not made clear whether the group of women make it across the border back into Mexico, and Zach’s personal redemption remains unfulfilled.52

By this point in the novel, coherence has disintegrated between editions. However, it is highly unlikely that readers discussing the novel would not notice this final change as it is so dramatic as to render an entirely different text. It is a far cry from small, minute surface changes to which Richards gestured; by this point, the text has broken away from close readings and into macro plot details.

Thus far, the thesis that Telephone may actually be about poorly rewarding close reading may seem stretched. Clearly, the differences between the versions here are significant and require the reader to pay attention. Can it really be tenable, though, to argue that this is a text about misprision and omission? The answer perhaps lies back in Everett’s game of chess. In the chapter entitled ‘Castling Short’ (Northeast and Northwest) and ‘De Homine’ (Southeast), two chess games take place, the nested version of which I have already examined above. The outer game of chess takes place over the course of the chapter and forms the mini-subheadings for the work (although they might be considered just ‘insertions’ or ‘interjections’ rather than subheadings). The sequence of moves up until the seventh position given by the novel are shown in Table 1.

The Chess Game Chapter Headings in Telephone.

| Move | White | Black | Page |

| 1 | d4 | Nf6 | 76 |

| 2 | Nf3 | b6 | 77 |

| 3 | c4 | e6 | 78 |

| 4 | Nc3 | Bb7 | 79 |

| 5 | Bg5 | Bb4 | 81 |

| 6 | e3 | h6 | 82 |

| 7 | Nd2 | Qc7 | 84 |

The Queen’s Indian defence here, coupled with the crypticism of chess notation, appears to offer an invitation for the reader to begin sleuthing and close reading. What does this particular game mean? What happens if we replay the moves precisely? How does this game relate to the overarching themes of the text as a whole?

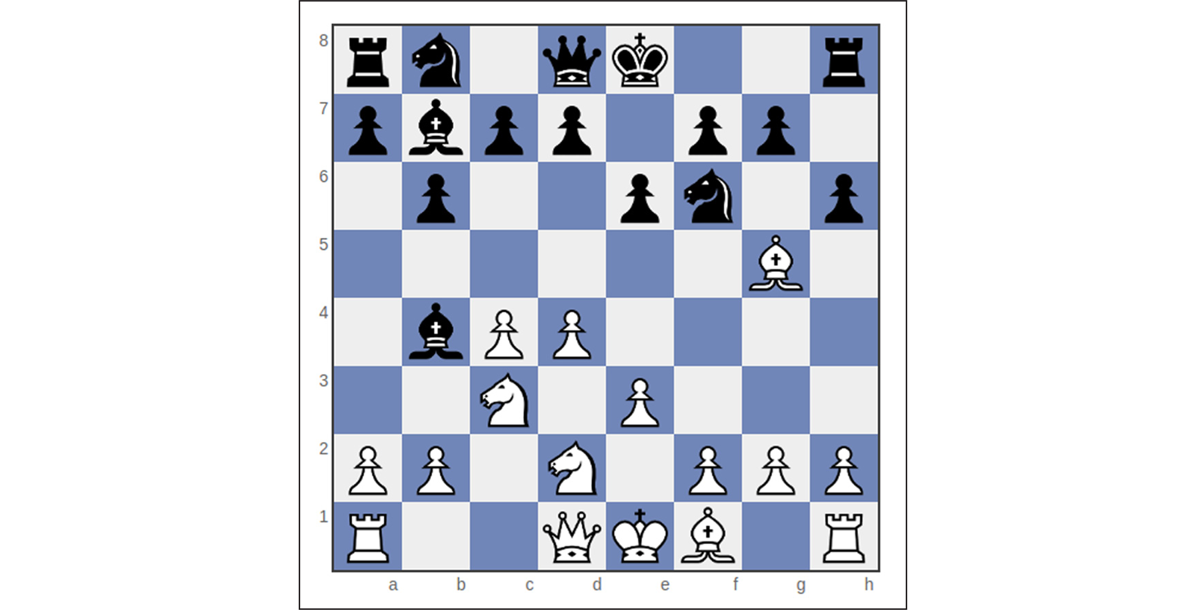

The problem is that, at the seventh move, the board breaks down. At the moment of black’s seventh move, shown in Figure 2, it is not possible for the queen to move to square C7, which is already occupied by a black pawn. Somewhere, between pages 82 and 84 (where the game-within-a-game occurs), there are moves that are not relayed to the reader. The invitation to close-read the situation, at this point, is confounded by missing information. The reader cannot ‘win’ the game of paranoid close reading for clues, because the data are not provided. Unlike the earlier game where the missing information could be interpolated, the endgame is unreachable, regardless of how much close attention one pays, because the information economy is imperfect.

While this lack of information may seem either to be an oversight or merely a frustration for overly pedantic readers, in the final part of this article I will argue that it is actually more to do with the narrative perspective. The move that the text makes, in withholding this information, is to re-orient the narrative perspective towards the illness of the child, Sarah, who has a neurological impairment. In withholding this information, the reader assumes the view of the unwell character, Sarah, even while the narrative remains focalised through Zach. The final move in this game, then, requires a foray into disability studies.

A Disability Perspective

Various schools of disability studies have, since the 1970s, highlighted the social construction of disability.53 In such models, disability is separate from impairment, and is often defined as ‘the relationship between people with impairments and a society that excludes them.’54 Hence, in such a model, it is society that disables people with impairments (for instance, by providing only stairs and not wheelchair ramps). As such, as David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder put it, ‘disability, like gender, sexuality, and race’ is ‘a constructed category of discursive investment.’55

Disability in art forms, culture, and society at large is often ‘used’ for various societal and narrative purposes. In Michael Bérubé’s phrasing, in his stunning work on intellectual disability and fiction, The Secret Life of Stories, disability can be ‘deployed’ in narrative in a host of challenging fashions.56 As Rosemarie Garland-Thomson charts it, there are five dominant – and prejudicial, oppressive, and disempowering – approaches to disability that can be ordered into a taxonomy:

First is the biomedical narrative that casts the variations we think of as impairment as physiological failures or flaws, as medical crises that demand normalization through technology or other allopathic measures. Second is the sentimental narrative that sees people with disabilities as occasions for narcissistic pity or lessons in suffering for those who imagine themselves nondisabled. Third is the narrative of overcoming that defines disability as a personal defect that must be compensated for rather than as the inevitable transformation of the body that results from encounters with the environment. Fourth is the narrative of catastrophe that presents disability as a dramatic, exceptional extremity that either incites courage or defeats a person. Fifth is the narrative of abjection that identifies disability as that which one can and must avoid at all costs.57

Often, literary texts can be as guilty as the rest of society in perpetuating such a narrative, as Rachel Carroll has shown, for instance, in Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending (2011).58 In Mitchell and Snyder’s framing, many, many narratives have a ‘discursive dependency upon disability as narrative prosthesis.’59 However, in certain cases, as in Everett’s novel, narrative techniques are rather used to re-situate the reader within an impairment/disability framework. This is not to say that this is the only frame within which disability can or should be understood, but it is the context that makes the most sense for Everett’s text.60

Everett has, in some ways, previously satirised discourses that take extensive care in defining disability. In I Am Not Sidney Poitier (2009), Everett’s pernickety narrator states, in his overly academic tone, that he ‘became obsessed with the concealment of FDR’s disabilities from the American public, my real interest being the definitions of disability and public.’61 That said, it is important to get these terms right, and a strict binary opposition between impairment and disability is, like the essentialism it sought to replace, an over-simplification. As Ato Quayson notes, ‘shifting the focus of disability to see it as primarily the product of social circumstances complicates even the notion of impairment’ since many impairments arise only as the result of those very social circumstances.62 In the writerly context, it is clear that if, as I go on to argue, the author disables the reader by narrative choice, it is the same choice that ‘gives’ the ‘impairment’ of Batten disease to the character Sarah. Of course, in a fictional context, all elements have a discursive root and there is no real biology at play. This causes, in some senses, a flattening of the disability-impairment dichotomy, because the intra-diegetic conferral of impairment has the socio-discursive characteristics of disability.

The crucial passage in Telephone that alerts the reader to the meta-thread of missing information lies in Zach and Meg’s discussion about whether they should tell Sarah of her impending slow decline. The central issue is not that Sarah will die in the near future, which is certain, but rather that, in the period leading up to her death she will experience an increasing number of seizures and incur substantial intellectual disability. Zach and Sarah confer on the matter thus:

‘I think we should tell Sarah everything,’ I said.

Meg did not lift her head from the pillow. ‘I disagree.’

I knew she would. I knew she would not only because I understood the argument for not telling the child but also because I imagined that she would disagree with whichever way I chose to proceed. Whether it was simply a matter of playing devil’s advocate to promote helpful discussion or just contrariness, I didn’t know. And I really didn’t care.

‘You think we should lie to her,’ I said.

Meg sat up. ‘I think we simply don’t tell her.’

‘Then what do we tell her?’

She lay back down. There would be no more discussion that night, and nothing had been decided. I didn’t want to lie to my daughter, but neither could I imagine telling her the truth. Of course, that was the stuff of it, not whether we would tell her the truth about her disease but could we.63

If read as a series of metatextual statements, this passage yields a matrix of possibilities that can be used to understand the text’s lapses in detail. One of the explanations that is raised by this discussion is that the narrator may be ‘parenting’ the reader. The textual elisions and omissions may, under such a model, be the narrator deciding not to tell the reader all details. Importantly, this is not, as the cited passage indicates, about lies. Indeed, Telephone opens with a discourse on truth: ‘People, and by people I mean them, never look for truth, they look for satisfaction. There is nothing worse, certain deadly and painful diseases notwithstanding, than an unsatisfactory, piss-poor truth, whereas a satisfactory lie is all too easy to accept, even embrace, get cozy with.’64 The untruth here, though, is a sin of omission, not of misrepresentation.

In light of this opening, Telephone asks the fundamental question of whether the pursuit of textual detail is the pursuit of truth or the pursuit of satisfaction. Indeed the text raises queries about wish-fulfilment in reading; do we read for what will give satisfaction, rather than what is truth on the page? This wish-fulfilment is why the resolution of a rhyme in a poem brings satisfaction, even when it may not be the most truthful poetic representation. The lure of the chess game in Telephone, with its arcane notation that reads like a code to be deciphered, may prompt readers to setup a board and follow the game through. However, in its omission, the text denies such satisfaction and instead gives the reader a hard truth.65 This illusion is also strengthened because the game of chess enforces a neater framework and tighter framework of causality than is possible (or desirable) in a novel.

The omissions should also be considered in terms of narratorial inability, as per the cited paragraph. If we believe that Telephone’s omissions are a result of the narrator deciding not to tell everything, then we should also take seriously the statements of Zach that this is due to an emotional inability to tell everything. The multiple versions of Everett’s text also give some credence to this apparent inability to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Each version serves as a vehicle by which the narrator can avoid pinning down definitive details and gradually undermines the reader’s confidence in the narrator’s reliability.

These readings are plausible. However, there is a better reading of the text than this focus on the conventional unreliable narrator. Instead, because the text is missing portions of detail that are denied to the reader, it appears to mirror Sarah’s pathology. That is, the reading experience parallels the effects of the neurological decline experienced by Sarah. It is important to note that literary disability studies must always be more than ‘whether any specific character can be pegged with a specific diagnosis’, as Bérubé puts it.66 At the same time, though, the decline in this condition takes the form of momentary lapses of concentration – seizures – in which events continue but the sufferer is unaware of what has transpired. Batten disease is also a progressive disorder, meaning that the condition becomes worse the longer the sufferer has had it.

There are many reasons to suspect that Telephone’s narrative style and structure is designed to provide a formal readerly experience of Batten disease. For one, the changes to the text between the versions become more severe only as novelistic time passes. The more pages into the text you are, the more severe and manifest are the variations between editions. The most significant plot changes (Paris, the smothering incident, and the final rescue of the women) all occur much later in the book’s development.67 The degeneration of textual coherence – perhaps also indicated by the two very different, splitting plot contexts of Sarah’s decline vs. the rescue in Mexico – is, like Batten disease, progressive.

A second compelling argument for this reading comes from the genetic patterning of Batten disease, which is an autosomal recessive condition.68 In such conditions, both parents are carriers although they do not, themselves, have the genetic expression; they are free of the disease. Given the complicated inheritance relationships of Telephone, in which three slightly different works interact with one another, with each text carrying a variant version of the code of an imagined, tripartite composite novel, but that only become symptomatic of degeneration when placed alongside one another, there is a further reason to suspect an interplay between textual and medical genetics in this work. Telephone only reveals itself as a text in pathological breakdown when the codes of the editions are combined, rather than when the versions sit alone.69

Assuming that one accepts this reading, there are two ways in which to appraise Telephone’s symptomatic casting. The first is to state that the reader of Telephone is impaired. In this medical model, the reader is unable to fill in the textual blanks due to a deficit of function; even if you read more than one edition, it is easy to miss small changes to detail. Such a reading would be in line with many pre-1970s assessments of disability. Some of the minor textual differences in Telephone hint at this model. Most readers are, in all honesty, unlikely to have the capacity to notice the difference between ‘turned to open the medicine drawer’ and ‘turned to the medicine drawer’ within a novelistic context.70 Telephone seems to test the idea that readers have unbounded actual physical capacity to read minute surface differences. As a result, following Mitchell and Snyder, the text ‘does not deny the reality of physical incapacity or cognitive difference.’71

However, this reading neglects the fact that Telephone actively disables the reader. The withholding of key moments in the novel is not something that happens due to a defect in the reader; it is a result of the author’s deliberate textual strategies. The simulated effect may be similar to impairment, but the novel actually functions as a societal mediator. Telephone’s silences and miscommunications are authorial choices, made (playfully) to prevent the reader from fully re-constructing any single narrative. This is another context in which we should, then, consider whether Everett’s claims to delegate authority to the reader are really merited. Certainly, there is a social interplay between reader and author at work. Yet, the author has made the decision to disable the reader by preventing any totalising interpretation.

What are the ethical consequences of this innovative, formal, structural, fictional representation of disability? Certainly, this tallies well with one of Quayson’s typologies of disability representation in which ‘the representation of disability oscillates uneasily between the aesthetic and the ethical domains.’72 These are instances where disability ‘acts as some form of ethical background to the actions of other characters, or as a means of testing or enhancing their moral standing.’73 The main plotline of Telephone, in which Sarah develops Batten disease, indeed somewhat follows the catastrophe narrative that Garland-Thomson outlines. It is one in which, after the diagnosis, ‘the world was different.’74 Yet, in casting the reader as the sufferer – in a formal pathologizing mode – Everett changes such discourse. In this world, the reader can (problematically) attempt to ‘overcome’ disability by close reading, if they believe it to be an impairment on their part. It seems as though the game is fair and, if you only read closely enough, attempting to fill in the blanks, you will come to the ‘right’ answer. However, the text will not actually allow such close reading to provide resolution; the social model prevails. The solution to the chess game remains unsolveable. The reader will have to suffer the inevitable consequences of the textual condition: ‘you can’t protect everybody. You just have to get the better of it or get the position that you want.’75 The fact that different versions of the text, however, pose different versions of the distressing smothering scene – perhaps the moment that would most conform to Quayson’s typology – suggests that Telephone is asking these questions at the level of multiple-textual form, rather than in plot progression.

These are the representational characteristics of disability, close reading as inattention pathology, and chess in Everett’s Telephone. Yet there is one final irony that must be considered in conclusion. The route to understanding Telephone as a novel that casts the reader as Sarah is one that, itself, requires close reading of the empty spaces in the text. Close reading is the only route to the understanding that Telephone is as much a novel about what isn’t said as what is. Yet close reading will not provide the ultimate solution. Instead, we are given a more problematic statement: ‘in those frightful, horrible flashes of seizure, I apperceived what it would be like to finally lose, surrender my daughter. The episodes were small destructions, and I withered alongside her each and every time.’76 In Everett’s moments of seizure and blankness, the moments of textual pathology, come the moments of clarity that act as a key for Telephone. Close reading the missing information – the blanks – in Everett’s chess games allows the reader to apperceive – a word that has the meta-sense of being aware of perceiving, and a term that Everett has re-used across many of his novels – what it is like to finally lose in the struggle between author and reader.77

Notes

- Percival Everett, Glyph (London: Faber and Faber, 2004), p. 70. [^]

- Percival Everett, Telephone (Southeast) (Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2020), p. 83. This novel is published in three different editions. Where the text remains the same between the three, I refer to the edition known as Southeast. Full coverage of the version variance will be addressed later in this article. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 83. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 84. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 7. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 53. [^]

- ‘Telephone Book Discussion’, Goodreads, 2020 <https://www.goodreads.com/topic/list_book/51541232-telephone> [accessed 4 September 2021]. One potential objection is that reader-response criticism might be a better paradigm within which to consider this negotiated relationship, as pioneered by Wolfgang Iser. This I leave to someone else, for another day. Wolfgang Iser, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995); Wolfgang Iser, The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1994). [^]

- Brian Rocha and Percival Everett, ‘A Conversation with Percival Everett’, Booth, 2021 <https://booth.butler.edu/2021/08/06/a-conversation-with-percival-everett/> [accessed 5 September 2021]. [^]

- James J. Donahue, ‘Voicing His Objections: Narrative Voice as Racial Critique in Percival Everett’s God’s Country’, African American Review, 52.1 (2019), 75–86 (p. 76) <https://doi.org/10.1353/afa.2019.0006>. [^]

- Zach Linge, ‘Retracing the Hype about Hyper into Percival Everett’, African American Review, 52.1 (2019), 5–16 (p. 5) <https://doi.org/10.1353/afa.2019.0001>. [^]

- Judith Roof, ‘Everett’s Hypernarrator’, Canadian Review of American Studies, 43.2 (2013), 202–15 (p. 205). [^]

- For more on Everett’s Western novels, see Michel Feith, ‘Philosophy Embedded in Space: Rethinking the Frontier in Percival Everett’s Western Novels’, African American Review, 52.1 (2019), 87–100 <https://doi.org/10.1353/afa.2019.0007>. [^]

- Percival Everett, Wounded (London: Faber, 2008), pp. 16, 18, 22. [^]

- Everett, Wounded, p. 25. [^]

- For more on the genre fusions and comedy of Everett’s Western novels, see Donahue. [^]

- Percival Everett, So Much Blue (Minneapolis, MI: Graywolf Press, 2017), pp. 5, 8, 19, 24, 31, 57. [^]

- Everett, So Much Blue, pp. 58, 85, 90, 237. [^]

- Everett, Glyph, p. 74. [^]

- See, for instance, Jonathan Culler, ‘The Closeness of Close Reading’, ADE Bulletin, 2010, 20–25 <https://doi.org/10.1632/ade.149.20>. [^]

- I.A. Richards, The Principles of Literary Criticism, 2nd edn (London: Routledge, 1926), p. 158. [^]

- I.A. Richards, Practical Criticism: A Study of Literary Judgment (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd, 1930), pp. ix, 6. [^]

- I.A. Richards, How to Read a Page: A Course in Efficient Reading with an Introduction to A Hundred Great Words (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1959), p. 15. [^]

- Andrew Elfenbein, The Gist of Reading (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018), p. 86. [^]

- Louis Althusser and others, Reading Capital: The Complete Edition, trans. by Ben Brewster and David Fernbach (London: Verso, 2015), pp. 17, 27. [^]

- David Stewart, ‘The Hermeneutics of Suspicion’, Literature and Theology, 3.3 (1989), 296–307 (p. 303); Cathy N. Davidson and David Theo Goldberg, ‘Engaging the Humanities’, Profession, 2004, 42–62 (p. 45). [^]

- Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus, ‘Surface Reading: An Introduction’, Representations, 108.1 (2009), 1–21 (p. 2) <https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2009.108.1.1>. [^]

- N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012), p. 59. [^]

- See Bruce Robbins, ‘Not So Well Attached’, PMLA, 132.2 (2017), 371–76 <https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2017.132.2.371>. [^]

- Rita Felski, The Limits of Critique (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015), p. 3. For a more detailed history of Felski’s use of Ricœur’s phrase, see Martin Paul Eve, Close Reading With Computers: Textual Scholarship, Computational Formalism, and David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), pp. 7–9. [^]

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, ‘Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid You Probably Think This Essay Is About You’, in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 123–51 <http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=1167951> [accessed 5 August 2017]; Best and Marcus. [^]

- Heather Houser, ‘Shimmering Description and Descriptive Criticism’, New Literary History, 51.1 (2020), 1–22 <https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2020.0000>. [^]

- Culler, p. 22. [^]

- Fore more on Everett as satirist, see Derek C. Maus, Jesting in Earnest: Percival Everett and Menippean Satire (Columbia, SC: The University of South Carolina Press, 2019). [^]

- Mitchum Huehls, ‘The Post-Theory Theory Novel’, Contemporary Literature, 56.2 (2015), 280–310 <https://doi.org/10.3368/cl.56.2.280>. [^]

- James Yeh, ‘Percival Everett Has a Book or Three Coming Out’, The New York Times, 3 May 2020, section Books <https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/03/books/percival-everett-telephone.html> [accessed 7 September 2021]. [^]

- Martin Paul Eve, ‘“You Have to Keep Track of Your Changes”: The Version Variants and Publishing History of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas’, Open Library of Humanities, 2.2 (2016), 1–34 <https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.82>; Martin Paul Eve, ‘Textual Scholarship and Contemporary Literary Studies: Jennifer Egan’s Editorial Processes and the Archival Edition of Emerald City’, Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory, 31.1 (2020), 25–41 <https://doi.org/10.1080/10436928.2020.1709713>. [^]

- Luc Herman and John M. Krafft, ‘Fast Learner: The Typescript of Pynchon’s V. at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin’, Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 49.1 (2007), 1–20 <https://doi.org/10.1353/tsl.2007.0005>; Albert Rolls, ‘The Two V.s of Thomas Pynchon, or From Lippincott to Jonathan Cape and Beyond’, Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon, 1.1 (2012) <https://doi.org/10.7766/orbit.v1.1.33>. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 78. [^]

- John Roache, ‘“The Realer, More Enduring and Sentimental Part of Him”: David Foster Wallace’s Personal Library and Marginalia’, Orbit: A Journal of American Literature, 5.1 (2017) <https://doi.org/10.16995/orbit.142>. [^]

- Rocha and Everett. [^]

- Percival Everett, Telephone (Northeast) (Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2020), p. 82; Percival Everett, Telephone (Northwest) (Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2020), p. 82; Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 82. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 119. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 136. [^]

- For a note on some of the other changes, see David Lerner Schwartz, ‘On Percival Everett’s Almost Secret Experiment in a Novel in Threes’, Literary Hub, 2020 <https://lithub.com/on-percival-everetts-almost-secret-experiment-in-a-novel-in-threes/> [accessed 7 September 2021]. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Northwest), p. 122. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), pp. 184–85; Everett, Telephone (Northeast), pp. 184–85. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Northwest), pp. 184–85. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Northeast); Everett, Telephone (Northwest); Everett, Telephone (Southeast). [^]

- Giuliana Adamo, ‘Twentieth-Century Recent Theories on Beginnings and Endings of Novels’, Annali d’Italianistica, 18 (2000), 49–76; Giuliana Adamo, ‘Beginnings and Endings in Novels’, New Readings, 1.1 (2011) <http://ojs.cf.ac.uk/index.php/newreadings/article/view/62> [accessed 30 January 2020]. On not quite the same lines, see also Frank Kermode, The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction: With a New Epilogue (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), pp. 215–16. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Northeast), pp. 215–16; Everett, Telephone (Northwest), pp. 215–17. [^]

- Several of Everett’s novels feature Other spaces on the American continent as foils for their main action. 1999’s Glyph has a segment where the baby, Ralph, is supposed to be transported to Mexico while So Much Blue features episodes set in El Salvador in the 1970s. [^]

- As a note: different people with disabilities/disabled people have very different perspectives on how disability should be construed. The author of this article has a set of physical disabilities and long-term health conditions but acknowledges that there is a plurality of views as to how disability should be understood. D. Christopher Ralston and Justin Ho, ‘Introduction: Philosophical Reflections on Disability’, in Philosophical Reflections on Disability, ed. by D. Christopher Ralston and Justin Ho, Philosophy and Medicine (Dordrecht: Springer Verlag, 2010), pp. 1–16; For more founding work in this field on the social model of disability, see Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2017), pp. 6–7. [^]

- Tom Shakespeare and others, ‘Models’, in Encyclopedia of Disability, ed. by Gary L. Albrecht (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006), pp. 1101–8 (p. 1103). [^]

- David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse, Corporealities (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2001), p. 2. [^]

- Michael Bérubé, The Secret Life of Stories: From Don Quixote to Harry Potter, How Understanding Intellectual Disability Transforms the Way We Read (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2016), p. 2. [^]

- Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, ‘Feminist Disability Studies’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30.2 (2005), 1557–87 (pp. 1567–68) <https://doi.org/10.1086/423352>. [^]

- Rachel Carroll, ‘‘Making the Blood Flow Backwards’: Disability, Heterosexuality and the Politics of Representation in Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending’, Textual Practice, 2014, 1–18 <https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2014.955818>. [^]

- Mitchell and Snyder, p. 5. [^]

- It is inevitable that this section will become caught in the ‘unavoidable disputes over disability terminology’ that are charted in Bérubé, p. 30. [^]

- Percival Everett, I Am Not Sidney Poitier (La Vergne: Influx Press Ltd, 2020), p. 49. [^]

- Ato Quayson, Aesthetic Nervousness: Disability and the Crisis of Representation (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2007), p. 1. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 76. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 3. [^]

- For more on truth in Everett’s work, see Jonathan Dittman, ‘“Knowledge2 + Certainty2 = Squat2”: (Re)Thinking Identity and Meaning in Percival Everett’s The Water Cure’, in Perspectives on Percival Everett, ed. by Keith B. Mitchell and Robin G. Vander, Margaret Walker Alexander Series in African American Studies (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2013), pp. 3–18. [^]

- Bérubé, p. 19. [^]

- It is interesting to consider which episodes could have been major diverging plot points in the text, but that were not. For instance, does Zach’s colleague. Hilary Gill, kill herself in every version of the novel? [^]

- See J. D. Cooper, ‘Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis’, in Encyclopedia of Movement Disorders, ed. by Katie Kompoliti and Leo Verhagen Metman (Oxford: Academic Press, 2010), pp. 291–95 <https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374105-9.00492-5>. [^]

- Perhaps, though, this argument too broadly conflates textual criticism and genetic criticism. For more, see Daniel Ferrer, ‘Genetic Criticism with Textual Criticism: From Variant to Variation’, Variants. The Journal of the European Society for Textual Scholarship, 12–13, 2016, 57–64 <https://doi.org/10.4000/variants.284>. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Northeast), pp. 9, 10; Everett, Telephone (Northwest), pp. 9, 10. [^]

- Mitchell and Snyder, p. 7. [^]

- Quayson, p. 19. [^]

- Quayson, p. 36. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 71. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 84. [^]

- Everett, Telephone (Southeast), p. 96. [^]

- The word ‘apperceived’ occurs prominently in Everett’s works and also in the secondary criticism. See Judith Roof, ‘So Much Blue: The Equanimity of Passionate Desperation’, African American Review, 52.1 (2019), 17–26 (p. 21) <https://doi.org/10.1353/afa.2019.0002>. [^]

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by a Philip Leverhulme Prize awarded by the Leverhulme Trust.

The author would also like to thank Sascha Pöhlmann for his detailed and constructive feedback, which significantly improved the article.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Adamo, Giuliana, ‘Beginnings and Endings in Novels’, New Readings, 1.1 (2011) <http://ojs.cf.ac.uk/index.php/newreadings/article/view/62> [accessed 30 January 2020].

Adamo, Giuliana, ‘Twentieth-Century Recent Theories on Beginnings and Endings of Novels’, Annali d’Italianistica, 18 (2000), 49–76.

Althusser, Louis, Étienne Balibar, Roger Establet, Pierre Machery, and Jacques Rancière, Reading Capital: The Complete Edition, trans. by Ben Brewster and David Fernbach (London: Verso, 2015).

Bérubé, Michael, The Secret Life of Stories: From Don Quixote to Harry Potter, How Understanding Intellectual Disability Transforms the Way We Read (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2016).

Best, Stephen, and Sharon Marcus, ‘Surface Reading: An Introduction’, Representations, 108.1 (2009), 1–21. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2009.108.1.1>

Carroll, Rachel, ‘‘Making the Blood Flow Backwards’: Disability, Heterosexuality and the Politics of Representation in Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending’, Textual Practice, 2014, 1–18. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2014.955818>

Cooper, J. D., ‘Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis’, in Encyclopedia of Movement Disorders, ed. by Katie Kompoliti and Leo Verhagen Metman (Oxford: Academic Press, 2010), pp. 291–95. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374105-9.00492-5>

Culler, Jonathan, ‘The Closeness of Close Reading’, ADE Bulletin, 2010, 20–25. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1632/ade.149.20>

Davidson, Cathy N., and David Theo Goldberg, ‘Engaging the Humanities’, Profession, 2004, 42–62. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1632/074069504X26386>

Dittman, Jonathan, ‘“Knowledge2 + Certainty2 = Squat2”: (Re)Thinking Identity and Meaning in Percival Everett’s The Water Cure’, in Perspectives on Percival Everett, ed. by Keith B. Mitchell and Robin G. Vander, Margaret Walker Alexander Series in African American Studies (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2013), pp. 3–18. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.14325/mississippi/9781617036828.003.0001>

Donahue, James J., ‘Voicing His Objections: Narrative Voice as Racial Critique in Percival Everett’s God’s Country’, African American Review, 52.1 (2019), 75–86. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1353/afa.2019.0006>

Elfenbein, Andrew, The Gist of Reading (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018). DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1515/9781503604100>

Eve, Martin Paul, Close Reading With Computers: Textual Scholarship, Computational Formalism, and David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019). DOI: < http://doi.org/10.21627/9781503609372>

Eve, Martin Paul, ‘Textual Scholarship and Contemporary Literary Studies: Jennifer Egan’s Editorial Processes and the Archival Edition of Emerald City’, Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory, 31.1 (2020), 25–41. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1080/10436928.2020.1709713>

Eve, Martin Paul, ‘“You Have to Keep Track of Your Changes”: The Version Variants and Publishing History of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas’, Open Library of Humanities, 2.2 (2016), 1–34. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.16995/olh.82>

Everett, Percival, Erasure (London: Faber, 2003).

Everett, Percival, Glyph (London: Faber and Faber, 2004).

Everett, Percival, I Am Not Sidney Poitier (La Vergne: Influx Press Ltd, 2020).

Everett, Percival, So Much Blue (Minneapolis, MI: Graywolf Press, 2017).

Everett, Percival, Telephone (Northeast) (Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2020).

Everett, Percival, Telephone (Northwest) (Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2020).

Everett, Percival, Telephone (Southeast) (Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2020).

Everett, Percival, Wounded (London: Faber, 2008).

Feith, Michel, ‘Philosophy Embedded in Space: Rethinking the Frontier in Percival Everett’s Western Novels’, African American Review, 52.1 (2019), 87–100. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1353/afa.2019.0007>

Felski, Rita, The Limits of Critique (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015). DOI: < http://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226294179.001.0001>

Ferrer, Daniel, ‘Genetic Criticism with Textual Criticism: From Variant to Variation’, Variants. The Journal of the European Society for Textual Scholarship, 12–13, 2016, 57–64. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.4000/variants.284>

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie, Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2017).

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie, ‘Feminist Disability Studies’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30.2 (2005), 1557–87. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1086/423352>

Hayles, N. Katherine, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012). DOI: < http://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226321370.001.0001>

Herman, Luc, and John M. Krafft, ‘Fast Learner: The Typescript of Pynchon’s V. at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin’, Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 49.1 (2007), 1–20. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1353/tsl.2007.0005>

Houser, Heather, ‘Shimmering Description and Descriptive Criticism’, New Literary History, 51.1 (2020), 1–22. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2020.0000>

Huehls, Mitchum, ‘The Post-Theory Theory Novel’, Contemporary Literature, 56.2 (2015), 280–310. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.3368/cl.56.2.280>

Iser, Wolfgang, The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1994).

Iser, Wolfgang, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

Kermode, Frank, The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction: With a New Epilogue (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Linge, Zach, ‘Retracing the Hype about Hyper into Percival Everett’, African American Review, 52.1 (2019), 5–16. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1353/afa.2019.0001>

Maus, Derek C., Jesting in Earnest: Percival Everett and Menippean Satire (Columbia, SC: The University of South Carolina Press, 2019). DOI: < http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7r41n8>

Mitchell, David T., and Sharon L. Snyder, Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse, Corporealities (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2001). DOI: < http://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11523>

Quayson, Ato, Aesthetic Nervousness: Disability and the Crisis of Representation (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2007).

Ralston, D. Christopher, and Justin Ho, ‘Introduction: Philosophical Reflections on Disability’, in Philosophical Reflections on Disability, ed. by D. Christopher Ralston and Justin Ho, Philosophy and Medicine (Dordrecht: Springer Verlag, 2010), pp. 1–16. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2477-0_1>

Richards, I.A., How to Read a Page: A Course in Efficient Reading with an Introduction to A Hundred Great Words (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1959).

Richards, I.A., Practical Criticism: A Study of Literary Judgment (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd, 1930).

Richards, I.A., The Principles of Literary Criticism, 2nd edn (London: Routledge, 1926).

Roache, John, ‘“The Realer, More Enduring and Sentimental Part of Him”: David Foster Wallace’s Personal Library and Marginalia’, Orbit: A Journal of American Literature, 5.1 (2017). DOI: < http://doi.org/10.16995/orbit.142>

Robbins, Bruce, ‘Not So Well Attached’, PMLA, 132.2 (2017), 371–76. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2017.132.2.371>

Rocha, Brian, and Percival Everett, ‘A Conversation with Percival Everett’, Booth, 2021 <https://booth.butler.edu/2021/08/06/a-conversation-with-percival-everett/> [accessed 5 September 2021].

Rolls, Albert, ‘The Two V.s of Thomas Pynchon, or From Lippincott to Jonathan Cape and Beyond’, Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon, 1.1 (2012). DOI: < http://doi.org/10.7766/orbit.v1.1.33>

Roof, Judith, ‘Everett’s Hypernarrator’, Canadian Review of American Studies, 43.2 (2013), 202–15. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.3138/cras.2013.012>

Roof, Judith, ‘So Much Blue: The Equanimity of Passionate Desperation’, African American Review, 52.1 (2019), 17–26. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1353/afa.2019.0002>

Schwartz, David Lerner, ‘On Percival Everett’s Almost Secret Experiment in a Novel in Threes’, Literary Hub, 2020 <https://lithub.com/on-percival-everetts-almost-secret-experiment-in-a-novel-in-threes/> [accessed 7 September 2021].

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky, ‘Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid You Probably Think This Essay Is About You’, in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 123–51 <http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=1167951> [accessed 5 August 2017]. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1215/9780822384786-005>

Shakespeare, Tom, Jerome E. Bickenbach, David Pfeiffer, and Nicholas Watson, ‘Models’, in Encyclopedia of Disability, ed. by Gary L. Albrecht (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006), pp. 1101–8.

Stewart, David, ‘The Hermeneutics of Suspicion’, Literature and Theology, 3.3 (1989), 296–307. DOI: < http://doi.org/10.1093/litthe/3.3.296>

‘Telephone Book Discussion’, Goodreads, 2020 <https://www.goodreads.com/topic/list_book/51541232-telephone> [accessed 4 September 2021].

Yeh, James, ‘Percival Everett Has a Book or Three Coming Out’, The New York Times, 3 May 2020, section Books <https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/03/books/percival-everett-telephone.html> [accessed 7 September 2021].