Introduction

Published in 2000, Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves has been categorized as simultaneously displaying “modernist maneuvers, postmodernist airs and post-postmodernist critical parodies.”1 Sebastian Huber argues that House of Leaves is a modernist novel, yet he addresses a clear tension between this modernism and the fact that the novel’s publication year “implies that [it]…is to be situated in postmodernity and is thus postmodernist, or, if we should believe the rumors, the novel is already a case of a post-postmodernist aesthetics.”2 Definitions of “post-postmodernism” have circulated since the turn of the century with some scholars calling it a “mutation” of postmodernism,3 an “oscillation between” modernism and postmodernism,4 or a movement toward post-irony set in motion by 9/11 and a return to realism.5 Huber argues that “House of Leaves embraces pre-postmodernist elements which intimate and legitimize a modernist reading” and this reading is rooted in “the dominant mode of rejuvenating past literary genres in recent fiction” which he sees as being “marked by the realist return.”6 A reading of House of Leaves as post-postmodernist in its inclusion of both postmodernist and modernist tenets is in keeping with many of these definitions, which share the common view that post-postmodernism includes a rehashing of both postmodernism and modernism. While such definitions of post-postmodernism champion a simultaneous re-use of postmodernism and modernism, the strongest of them do so by highlighting the remarkable influence of digital technologies on twenty-first century literature.7

House of Leaves is arguably postmodernist in its metafiction and modernist in its focus on interiority, but it is also crucially “marked by digitality,” as N. Katherine Hayles would say.8 Hayles locates a hybridity in the novel where “the recursive dynamic between strategies that imitate electronic text and those that intensify the specificities of print reaches an apotheosis, producing complexities so entangled with digital technologies that it is difficult to say which medium is more important in producing the novel’s effects.”9 Hayles lists multimodality, layered text, multiple data streams, and code as digital entities that shape the work, ultimately suggesting that House of Leaves responds “to the digital environments that…affec[t] cognitive modes.”10 Similarly, Brian Chanen suggests that House of Leaves demonstrates how “the hyperlinked, networked digital environment has influenced the structure of print fiction and the ways in which a reader is encouraged to approach print text.”11 Jessica Pressman assesses this hyperlinked environment through the blue-font instances of the word “house” which she calls “colored signifiers [that] are textual acts of ‘remediation,’”12 and Lindsay Thomas highlights the presence of this hyperlinked environment beyond House of Leaves, suggesting that it connects all his novels, “implicat[ing]” the reader “within this intertextual relationship” and “the living link that connects each novel to the other” (389). The post-postmodernist potential of House of Leaves, in my view, is fully realized through the novel’s encapsulation of a dialogical tension between postmodernist and modernist tenets, rehashed within the novel’s aforementioned, inherent digitality. That is, House of Leaves is not a novel about the internet, but rather, it functions as a digital, textual machine, operated through experimental, nonlinear, and labyrinthian typography that mimics digital networks and necessitates a physical relationship between reader and codex.

If House of Leaves is a post-postmodernist, textual machine, with typography and materiality that imitate digital networks, then Danielewski’s more recent series, The Familiar, is even more so, yet it mimics the internet’s seeming infinite output, rather than “the computer’s omnivorous appetite,”13 reflecting the twenty-first century media ecology wherein the reader’s use of a smartphone plays a direct part in the reading process. This article defines “.compostmodernism” as a successor to postmodernism through an explication of The Familiar, which I argue is an example of .compostmodern textual machinery, a system of two interconnected “machines” (one abstract, the other physical) that are co-dependent and mobilized by the novel’s typography and materiality. The Familiar exemplifies .compostmodern textual machinery in that its experimental typography becomes the visual manifestation of literary cyber-consciousness, which I have defined elsewhere as a post-postmodernist narrative strategy for communicating character consciousness by amalgamating postmodernist irony and modernist stream of consciousness within the particular context of twenty-first century digitality. In visually manifesting character cyber-consciousness, the typography actualizes the digitality of character interiority, ultimately drawing attention to the work’s status not only as literary artifice, but also as textual machinery. This typographical layer of .compostmodern textual machinery works to highlight the “visuality” of the twenty-first century “computational” novels that Hayles identifies in her work on intermediation,14 but interestingly, the demands of such experimental typography instantiate a physical relationship between reader and codex that emphasizes the novel’s materiality and requires the reader to engage with the text both physically and digitally. This digital engagement incorporates the internet not only as a crucial supplement for the reader to seek reference, translation apps, and supplementary (albeit obscure) Danielewski publications, but also as a medium for the reader to supplement the novel via social media output and online reading communities on MZD forums, Reddit, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.15

Defining .Compostmodernism

I define .compostmodernism as a successor to postmodernism that involves the literary composting of “dead” and bygone postmodernist and modernist literary tenets with twenty-first century digitality in content, narrative form, typography, materiality, and medium. The term “compostmodernism”—sans the “.” to “.com”—is not wholly my own invention, as it has been used in the recent past to refer to discussions of environmental composting as well as plagiarism, borrowing, and literary collage.16 Most notably, it has been attributed to Kjartan Fløgstad, who uses it to describe “a mixture of old and new literary styles…as well as…a combination of serious and popular genres.”17 In an ecological sense, “compost” refers to “a mixture of various ingredients for fertilizing or enriching land,”18 and in a literary sense, it refers to “a literary composition, compendium.”19 My use of the term, like Fløgstad’s, involves a combination of literary styles, but rather than simply mixing old and new styles, .compostmodernism proposes that a combination of “dead” styles fertilize the growth of a new literary style within the specific context of digitality. The word “compostmodernism” has also, in recent years, “appeared in discussions on digital art, in connection to…bastard pop, mixology, open source, mash-ups and cut-ups, under the label of ‘remix culture,’”20 although in this way, it is specifically pertinent to digital music.21 My literary definition of .compostmodernism involves a certain degree of remixing, but it specifically engages with the ways digitality inflects print literature through a breaking down and decomposition of bygone literary qualities.

Most notably, the term .compostmodernism retains both titles of its predecessors, “postmodernism” and “modernism,” signaling how it necessitates a composting of literary tenets from both literary aesthetics. One of the most important ways postmodernism figures into .compostmodernism’s compost metaphor is through its perceived death that many scholars attribute to September 11, 2001. .Compostmodernism engages with Robert McLaughlin’s idea that 9/11 “demand[ed] a reconsideration of postmodernism”22 in a particularly American context as, “[i]n the days after the towers fell, journalists never tired of announcing the end of irony.”23 While .compostmodernism certainly does not support that 9/11 killed irony, it embraces the notion that, at the turn of the century, “irony as a means of engaging the culture was exhausted,”24 and uses this as a means of reconsidering irony in twenty-first century literature. With this, .compostmodernism also incorporates the resulting attribution of “new sincerity” to post-9/11 literature that works against postmodernism’s preoccupation with irony25 and is often associated with David Foster Wallace’s insistence that “the next real literary ‘rebels’” might “dare to back away from ironic watching,” revert back to “single-entendre values,” and “risk the…accusations of sentimentality, melodrama” and “credulity.”26 But rather than a blatant rejection of irony in favor of sincerity, .compostmodernism involves what McLaughlin calls “the challenge of the post-postmodern author”: “to write within the context of self-aware language, irony, and cynicism, acknowledge them, even use them, but then to write through them, to break through the cycle of self-reference, to represent the world constructively, to connect with others.”27 Within .compostmodernism’s composting metaphor, postmodernism’s “death” here proves fertile for contemporary authors who might use such irony as a means of pinpointing and exposing its new position within twenty-first century literature which, in keeping with Vermeulen and van den Akker’s metamodernism, “can no longer be explained in terms of the postmodern” since “they express a…hopefulness and…sincerity that hint at another structure of feeling.”28

.Compostmodernism certainly shares this complex co-existence of postmodern irony and sincerity, but it more overtly involves a concomitance of postmodernist irony and self-reference, and a modernist valuation of interiority through stream of consciousness. Yet, rather than an “oscillation”29 between postmodernism and modernism à la metamodernism, .compostmodernism utilizes these characteristics in their “dead” forms in order to instantiate their fertile renewal through their dynamic and irresolvable tension. Above all, .compostmodernism’s composting of their mutual persistence necessarily takes place in and amidst the fast-paced, digital world such that characteristics of postmodernism and modernism are combined, repurposed, and reborn, but this is crucially within a digital environment where the very status of (print) literature is influenced, dictated, and questioned by the prevalence of the internet, social media, apps, code, game culture and so forth. The “.com” in .compostmodernism embraces Linda Hutcheon’s insistence that post-postmodernism stems from “electronic technology and globalization” which have transformed how we experience the language we use and the social world in which we live.30 It also draws on Kirby’s celebration of the “computerization of the text”31 but retaliates against his insistence that post-postmodernist (digimodernist) print literature does not exist,32 as .compostmodernism’s composting of postmodernist/modernist elements through digitality can manifest itself in print literature through content, form, typography, materiality, and medium.

.Compostmodernism: Cyber-consciousness and .Compostmodern Textual Machinery

Content is .compostmodernism’s most basic avenue, often exemplified through the “internet novel”—texts that engage with contemporary digital culture through a postmodernist/modernist tension thematically. But form accounts for the more nuanced ways in which a postmodernist/modernist tension is digitally rendered in narrative strategy, namely through what I call literary cyber-consciousness. Cyber-consciousness—a crucial aspect of .compostmodernism that accounts for its formal expression—refers to a .compostmodern narrative strategy that exposes how human consciousness functions like the digital technology that so heavily mediates it through a productive tension between modern and postmodern formal features, predominantly postmodernist irony and self-reference, sincerity, and modernist stream of consciousness. Rooted in Hayles’ intermediation, which involves the “in-mixing of human and machine cognition,”33 cyber-consciousness fuses character subjectivity, identity, interiority, memory and thought with byproducts of the digital computer such as the internet, visual media, hyperlink, memory, downloading, streaming, sharing, storage, and social media platforms.

In .compostmodern machinery, it is cyber-consciousness—the exemplification of .compostmodern form—that can be visually manifested in experimental typography, producing a physical reading experience that highlights the materiality of the book through a kind of textual machine. .Compostmodern textual machinery is crucially rooted in the “textual machine,” a concept derivative of Alexander Starre’s “metamedia,” N. Katherine Hayles’ “technotext,” and Espen Aarseth’s “cybertext.” It borrows from Starre metamedia’s “artistic self-reference that systematically mirrors, addresses, or interrogates the material properties of its medium…draw[ing] attention to the status of texts as medial artifacts and examin[ing] the relationship between the text and its carrier medium, such as the printed book”34—which I view as undoubtedly postmodern and which accounts for .compostmodernism’s necessary inclusion of postmodernist self-reference.35 .Compostmodern textual machinery also draws on Starre’s insistence that “central aspects of digital print culture such as typographic experimentation…manifest the enduring relevance of literary modernism.”36 But, rather than locate an “enduring” modernism in literature based on a connection between literary modernism and “printing practices in the late nineteenth century,”37 .compostmodern textual machinery locates a lingering modernism within its cyber-consciousness, where stream of consciousness narrative is digitally realized through typography.38

In addition to Starre’s metamedia, .compostmodern textual machinery borrows from Hayles’s “technotext,” which she defines as that which “connects the technology that produces texts to the texts’ verbal constructions,” the notion that “the physical form of the literary artifact always affects what the words (and other semiotic components) mean.” Hayles’ technotext does not address the tension between postmodernism and an “enduring” modernism, but it introduces the “writing machine” which includes the actual inscription technologies that physically construct literary texts, as well as the action that technotexts carry out “when they bring into view the machinery that gives their verbal constructions physical reality.”39 .Compostmodern textual machinery incorporates Hayles’ insistence on a relationship between materiality and semiotic meaning in that the .compostmodern novel itself can be a textual machine, but more importantly, it draws on her “writing machine” as both the digital technology that “writes” the book as well as the “machinery” that bridges “verbal constructions” and “physical reality”—or, to put it more simply, the reading system that connects semiotic meaning, reader and physical codex.

Finally, .compostmodern textual machinery requires the interactive role of the reader, drawing from Espen Aarseth’s “cybertext” the notion that materiality has more to do with “the mechanical organization of the text” wherein “the intricacies of the medium” offer “an integral part of the literary exchange” (emphasis added).40 Establishing that “cybertext” is not limited to “the study of computer-driven (or ‘electronic’) textuality,”41 Aarseth defines it as “the wide range (or perspective) of possible textualities seen as a typology of machines, as various kinds of literary communication systems where the functional differences among the mechanical parts play a defining role in determining the aesthetic process.”42 Aarseth’s focus on literary exchange and communication highlights the crucial role played by the reader in the textual machine. While the book as “a material medium” works in tandem with the “collection of words” that makes meaning, Aarseth appoints the “operator” (the reader or user) as the third component to his textual machine. For Aarseth, “[t]he boundaries between [“the operator,” “verbal sign” and “medium”] are not clear but fluid and transgressive, and each part can be defined only in terms of the other two.”43 While Starre’s and Hayles’ textual machines remain more focused on the materiality of the codex, .compostmodern textual machinery incorporates Aarseth’s suggestion that the role of the reader as “operator” is necessary to the machine’s function.

.Compostmodern textual machinery has a dual structure. The first structure, the .compostmodern codex, is like Aarseth’s textual machine in that it involves a “fluid” relationship between “verbal signs” and “medium.” However, it differs from Aarseth’s textual machine in that the role of the “verbal signs” is more nuanced than simply either production or consumption. First, these “verbal signs” mobilize the self-reflexivity of the codex where the .compostmodern novel is not only aware of its status as material artifact but more importantly is aware of its status as textual machine. Second, the “verbal signs” in the .compostmodern codex, when typographically experimental, offer the visual manifestation of cyber-consciousness, actualizing the intermediation between consciousness and digital machine through textual imagery. While Aarseth uses “medium” to describe the relationship between verbal signs and the reader, the .compostmodern codex uses materiality because it is the typographical experimentation that physically demands the reader to engage with the codex, drawing attention to both the work’s materiality and digitality; herein lies the necessary connection between the .compostmodern codex and the second structure of machinery, .compostmodern operation.

.Compostmodern operation is not unlike in Aarseth’s “cybertext” where the role of the reader/“operator” is crucial, but here, the reader becomes involved in a complex, symbiotic relationship with the codex, and the internet. .Compostmodern operation refers to the reading process that necessarily includes the reader’s engagement with and reliance on internet technologies for supplementation to enhance and explicate the codex’s complexities, in terms of semiotic meaning and obscure reference, and as a medium for the reader to supplement the text itself. Uniquely, this relationship between reader and internet makes an author of the reader, awarding them an interactive capability to figuratively shape the .compostmodern codex. In .compostmodern operation, there is a cyclical nature to the reader’s oscillation between codex and screen wherein interpreting the verbal signs and semiotic meaning can be inaccessible without the internet search engine, translation apps, supplementary software, and social media platforms. .Compostmodern textual machinery is a reconfiguration of the textual machine, incorporating the computer (and namely, the internet) as a necessary “extension of ourselves”44 and, then, of the codex itself.

Yet, it is important to note that .compostmodern textual machinery is not simply a reading process wherein the reader googles things. The inclusion of internet and digital supplementation defines the reader’s role as operator, constituting the interactive aspect of .compostmodern literature where the reader is invited and sometimes required to contribute to the text. The idea of interactive reading is a common element in many post-postmodernist perspectives on literature. For Kirby, the digimodernist text invites the reader to “intervene textually” and to “physically make text”45 and in Aarseth’s cybertext and “ergodic literature,” “the cybertext reader is a player, a gambler” while “the cybertext is a game-world or world-game” and “it is possible to explore, get lost, and discover secret paths in these texts, not metaphorically, but through the topological structures of the textual machinery.”46 Focusing more on the physical relationship between operator and codex, Aarseth promotes an aggressive engagement wherein the narrative itself is impacted and shifted by the choices and actions of the reader. .Compostmodern operation similarly invites the reader to interact with the codex, but this interactivity is not restricted to the physical traversal of the codex, to the question of linearity in narrative, nor is it limited to a two-part communication between reader and computer. The interactive nature of a .compostmodern novel can be physical, but it is also semiotic, digital and social. Adam Hammond explores “how interactivity serves to reinvigorate traditional modes of literary analysis such as narratology,”47 and .compostmodern operation similarly transcends the reader’s physical engagement with the text. In .compostmodernism, this interactivity can include the multiplicity of readers and authors facilitated by the internet where reading communities allow readers to share theories, experiences and interpretations, interacting with others in a text-based, digital environment.48 In .compostmodern operation, the reader similarly writes into the text through online social media, but the text does not eclipse reader response, nor does reader response eclipse the text. In entering an online community, the reader opens up the opportunity for communal authorship of the text in question, figuratively expanding on and developing the codex.

Machine One: The .Compostmodern Codex

The Familiar emerges as a .compostmodern codex first in that, throughout the volumes, Xanther’s interiority exemplifies .compostmodern cyber-consciousness as it playfully evokes the expanse and seeming infinitude of the internet. This infinitude is a thematic that is inherently .compostmodern due to the ways in which the internet is often perceived as having no end. It draws on Kirby’s “onwardness” or “the birth of the endless narrative” where “the shape and detail” of “digimodernist endlessness…emerges from the social, cultural, and technological specificity of the electronic-digital world.”49 But unlike digimodernism, which Kirby suggests is non-existent in print literature specifically,50 .compostmodernism involves the formal, typographical and eventually material actualization of a similar infinitude through character cyber-consciousness in print literature.

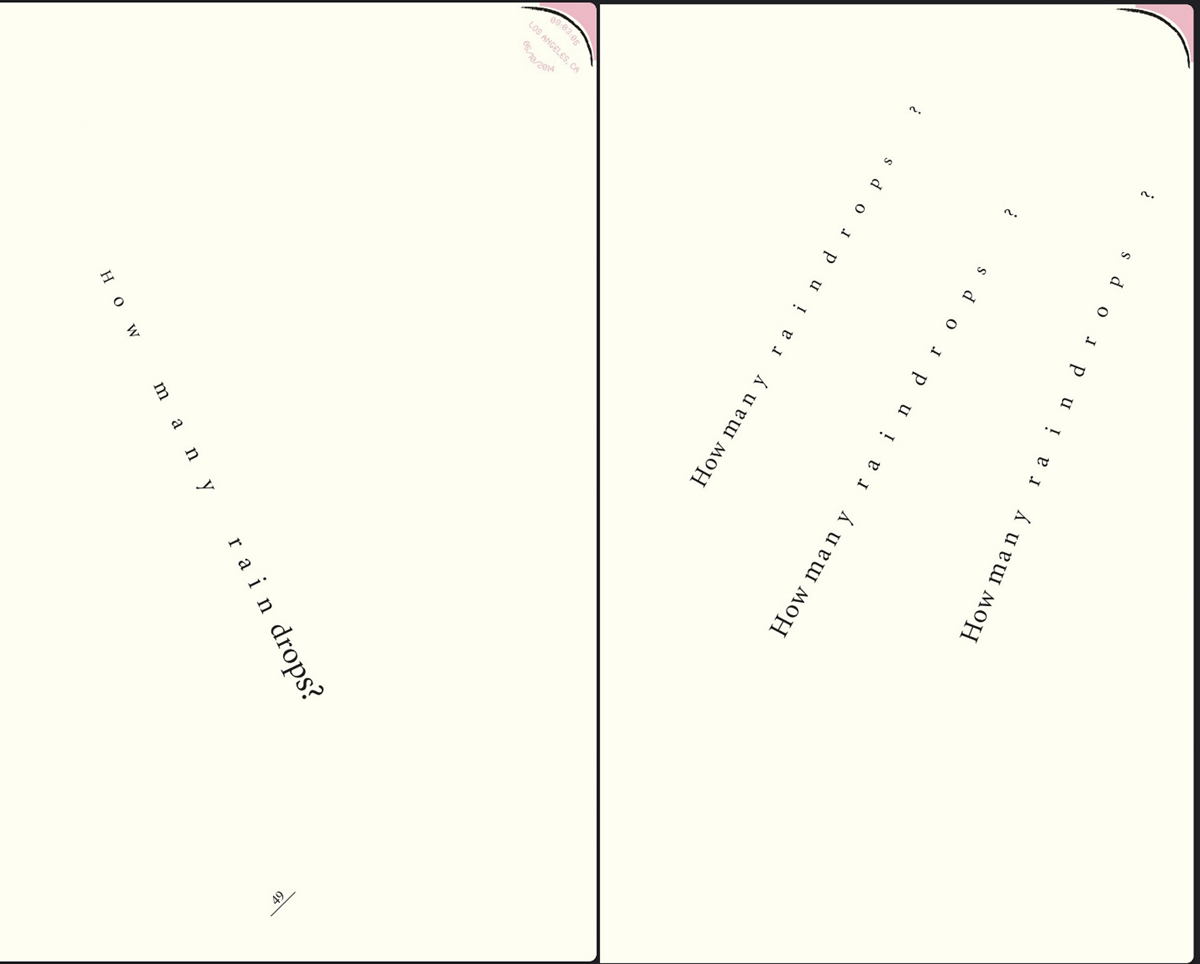

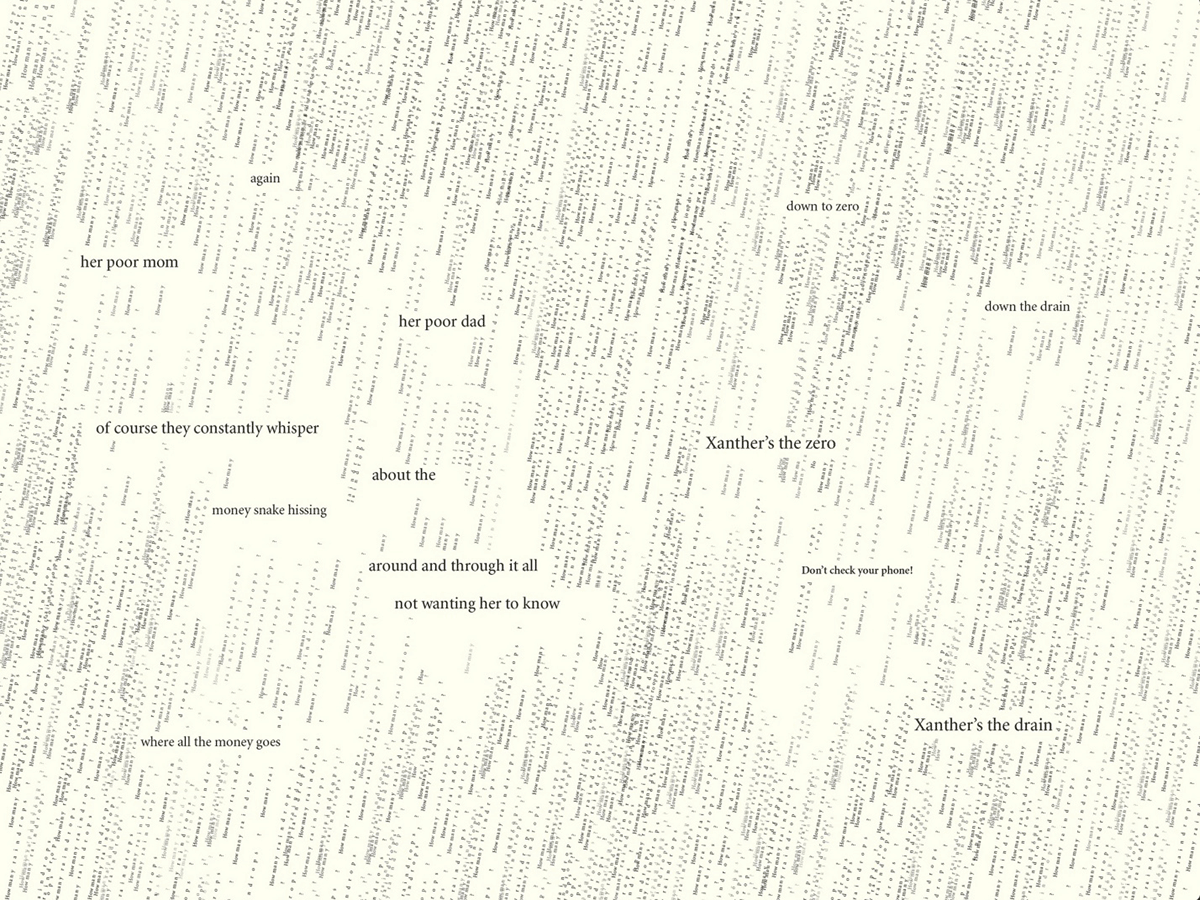

One Rainy Day in May opens with the Henry David Thoreau quote, “It is not worth the while to go round the world to count the cats in Zanzibar” (TFv1 48), which parallels Xanther’s question, “How many rain drops?” (TFv1 49) as, like the hypothetical quest to count the cats in Zanzibar, Xanther’s attempts to determine the exact number of rain drops is not so much a fruitless endeavour as an impossible task. “How many raindrops?” highlights infinitude more generally in Xanther’s consciousness first in that an answer is humanly impossible, and second in that Xanther’s preoccupation with locating the number of raindrops is an example of “what Anwar has dubbed her Question Song” (TFv1 115). That is, the question is layered in another shroud of seeming infinitude as the Question Song itself is also depicted as having no end since Xanther’s questions only ever lead to more (TFv1 61, 85). When Xanther’s interiority depicts her Question Song, she often commits a self-referential enactment of the Question Song itself. For example, when she rapidly flips through radio stations in the car with Anwar, her seemingly endless succession of questions mirrors the questions themselves, which are all about the impossibility of accessing infinity:

So many questions, so many possibilities, so many stations. Stations on stations, and hiding stations too, right?, because these are only the numbers for this area, what about those a state over?, two states over?, so many states, and if Xanther could hear them all at once, would that sound like forever?, maybe if Xanther arrowed fast enough through all the stations, it would sound like all at once, would that be a sound of endlessness?, a sound that’s really only one thing?, and could a dog be imagined that way too, all types experienced as one type? (TFv1 460)

Here, Xanther’s very act of asking the questions in her cognitive stream mirrors the infinitude about which she inquires at the same time as it embodies a kind of digital information overload within her cognition—an overload that is signaled, earlier on, when she asks amidst another torrent of questions, “What kind of counting equals this sort of overwhelmingness?” (61). This correlation between the Question Song and the infinitude on which she reflects is illustrated through the punctuation, as her questions, all independent clauses followed by question marks, are so often strung together with excessive commas as a means of emulating this ongoing list of questions. The text draws a further explicit parallel between the impossibility of counting the raindrops and the endlessness of Xanther’s Question Song when Astair equates Xanther’s “myriad questions about rain” to “the onslaught of water falling outside” (TFv1 115). The description of the rain as an “onslaught” paired with the description of Xanther’s question as existing in a “myriad”—both terms that connote quantities too large to count—emphasizes this parallel whereby the uncountable number of raindrops is a metaphor for Xanther’s consciousness, raining with infinite questions.

While Xanther’s obsession with the seemingly endless rainfall and her Question Song more generally establish her consciousness as accented by the theme of infinitude, her cyber-consciousness more overtly emerges through the association between her consciousness and an internet search engine. Anwar and Xanther’s shared affinity for internet searches allows Xanther’s Question Song to be digitally actualized: “[Xanther] and Anwar Wiki a lot, at night especially, they’re both night owls, going ‘deep’ or ‘thick’ on something, anything, trying to answer as many questions as possible” (TFv1 57). It is not clear whether or not Anwar and Xanther are writing content on Wikipedia or seeking it out, but regardless, the internet is described as a vehicle for Xanther to entertain her seemingly infinite “Question Song.” Assuming they seek content, the internet search is analogous to Xanther’s Question Song because the internet “hits” provide infinite answers to parallel her endless questions. This parallel illustrates the intermediation between Xanther’s consciousness and the internet that supplements her infinite questions, underscoring her cyber-consciousness.

Danielewski often uses free indirect discourse to ensure that Xanther’s interiority bleeds through the narrative in One Rainy Day in May (TFv1 50), and in instances like this, the narrative emulates her twelve year-old perspective, incorporating the emojis through which she thinks through emotions (TFv1 60–61) and (sometimes) sacrifices grammar in order to give her thoughts and questions a click-like momentum imitative of an internet rabbit hole. In keeping with cyber-consciousness’s digital reinvention of modernist stream of consciousness, Xanther’s chapters include stream of consciousness divergences that embody digital digression. The erratic leaps that Xanther’s consciousness often makes are suggestive of the ways in which hyperlinks function in the digital environments on which she so heavily relies to answer her infinite questions. The narrative highlights her cyber-consciousness in that it draws on modernist stream of consciousness, presenting the “continuous flow of” her “mental process, in which sense perceptions mingle with conscious and half-conscious thoughts, memories, expectations, feelings, and random associations.”51 However, this stream of consciousness is complicated by the self-consciousness of her reflections: i.e. cognitively streaming an infinite series of questions about the very impossibility of infinity. Because the novel’s content already makes overt steps to associate Xanther’s cognition with digital infinitude and the search engine, these jumps within the narrative can be understood through the hyperlinks that shape an internet search.

Perhaps even more revealing of Xanther’s cyber-consciousness are her epileptic seizures, which emerge as metaphorical “overloads” within her cyber-consciousness. Seizures are “paroxysmal event[s] due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity”52 that often occur when there is “a sudden surge of electrical activity in the brain.”53 Peter Wolf surveys the meaning behind epileptic seizures in literature,54 suggesting that the epileptic seizure has been a metaphor for emotional “breakdown[s]” or the result of “emotional crisis.”55 Xanther’s seizures are not emotional breakdowns per se, but given that they occur due to synchronous activity and electricity, and in the context of literary cyber-consciousness, Xanther’s seizures can be read as digital “breakdowns” or glitches in her brain when met with too much information. Astair describes Xanther’s seizure at Dov’s funeral as “Synaptic. ((short circuit?)…” (TFv1 240). Even Xanther similarly reflects on this after viewing a poster in Anwar’s office that reads, “If you can’t handle YOUR INFORMATION, you’re not overwhelmed…YOU ARE AN ASSHOLE” (TFv1 349). Xanther relates Mefisto’s “prank” of overloading her parents’ inboxes with infinite digital messages to her own epileptic condition:

It makes her think of Mefisto and the torrent of unwanted calls and e-mails he unleashed on her parents. Did that make him the A-hole? Or was Mefisto making A-holes out of Anwar and Astair because they couldn’t handle the information? Then a sad thought creeps up: sometimes people describe seizures as an overwhelming amount of information in the brain. Did that make Xanther an A-hole? (TFv1 350)

Xanther explicitly compares her brain to a computer by equating her inability to avoid seizures to a digital machine’s inability to function when overloaded with data, which is in keeping with Anwar’s reflection that the message overload caused by Mefisto prompted a “telephonic seizure” (TFv1 87). This is later reiterated when Xanther describes Mefisto’s prank as running its course “like a seizure” (TFv1 505). It is the seeming infinitude of information that, like a digital system, becomes overloaded within her cognition. So, when she bombards herself with countless questions such as the number of raindrops, she “grips her seat belt” and “clamps teeth tight” (TFv1 67), and we learn that her question overload almost sparks an epileptic seizure. Her cyber-consciousness is apparent in that her brain functions like a computer that short-circuits, often in these moments of synchronicity.

While Xanther’s cyber-consciousness is present throughout the narrative, it is the typographical experimentation that visually actualizes her cyber-consciousness, which plays a crucial role in the novel’s .compostmodern machinery. In addition to Xanther’s question, “How many raindrops?” invoking infinitude, these raindrops truly do appear on the page as Danielewski typographically arranges her questions in a way that marries form and content. In the opening pages of One Rainy Day in May, Danielewski typographically arranges “how many raindrops?” in the shape of a raindrop before plunging into Xanther’s frantic and chaotic consciousness, wherein each subsequent appearance of this question multiplies:56

The progressive multiplication of the raindrops over the course of the chapter mirrors the question overload in Xanther’s interiority. Like her questions, the raindrops she ponders are typographically presented as increasingly countless and seemingly infinite (TFv1 55, 62–65, 68–69):

This typography visualizes Xanther’s consciousness, but more importantly it highlights how Xanther’s consciousness embodies a kind of .compostmodern infinitude. Of course the number of typographical “raindrops” on the page is finite, but the visuals emulate the same infinitude that consistently bombards Xanther’s interiority. This rainfall is made more overtly digital later on in Anwar’s office when Glasgow relates the code on the screen to the opening of The Matrix, which Xanther thinks resembles rainfall: “Code kept scrolling down the screen like it was endless, maybe it was endless, and actually it did look a bit like rain” (TFv1 344). Amidst Xanther’s quest to understand Anwar’s game engine, Danielewski renders her Question Song (“How many raindrops?”) akin to “endless” digital code in a way that is in keeping with .compostmodernism’s thematic infinitude.

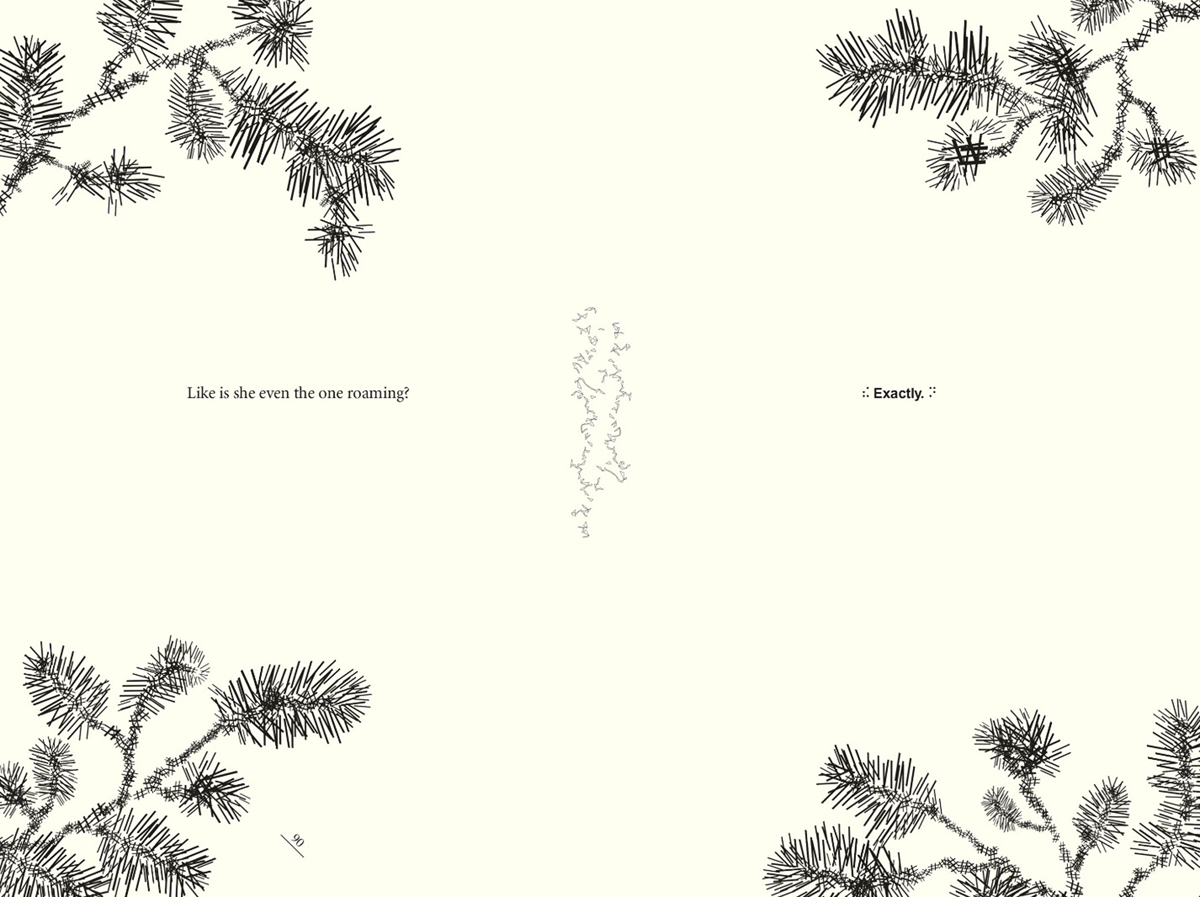

Xanther’s cyber-consciousness is more overtly manifested through typography in Into the Forest when her brain becomes overloaded by a “forest” of thoughts, illustrated by countless symbols associated with the digital. The title of the volume, Into the Forest, presupposes this development, and it is in a dream that she creates this branched and forested landscape in her mind comprised of hashtags and forward slashes:

Similarly, the stone eyes that Xanther keeps seeing on the eyes of those around her and on her own face after she takes Redwood in are typographically constructed with “@” symbols (e.g. TFv2 245, 371).57 Although the unfinished series of the novel leaves many doors and windows open,58 there is a digital connectivity suggested by these typographical constructions of Xanther’s cognitive function. Both hashtags and “@” symbols are used to connect files and/or webpages by creating hyperlinks. Hashtags allow individuals to connect particular words or phrases to digital entities such as Instagram posts, Snapchat Stories, Facebook posts, YouTube videos and so forth. Similarly, the “@” (at sign) is used to create a “handle” or name for online users—for example, @markzdanielewski is Danielewski’s Instagram handle. Like a hashtag, when used on a social media app, a handle creates a hyperlink to that user’s profile page, and such use will tag the user and notify them to read or view the digital content they have been hyperlinked to. The fact that Xanther’s forest and stone eyes are made up of these digital symbols in particular suggests how her interiority is influenced and impacted by this connective digital technology, further actualizing the digital machinery of her cyber-consciousness. Further, because hashtags and at signs play a crucial role in digital material going viral, in Xanther’s cyber-consciousness they suggest a lack of control and singularity in Xanther’s thoughts. Like a series of hashtags, Xanther’s cyber-consciousness makes seemingly infinite and continuous connections, jumping from one thing to the next like links through a digital jungle. And at the same time, like a viral video, Xanther’s interiority lacks control, location, memory and at times, ownership.

While Xanther’s cyber-consciousness is visually actualized through typographical experimentation, the typography throughout The Familiar also contributes to the novel’s metafictional nature, accounting for .compostmodernism’s use of postmodernist self-reflexivity. For example, the narrative overtly references Anwar’s computer code interiority while employing it through typographical experimentation: “Anwar’s thoughts torque even more, invert, and bind [in the absurd code that mocks any actual links of his trade {forget C++, Lua, Python, Java <even Clojure <<for example>>>}meted out in the very cages Astair has described {at times} as her own thoughts {<though rounder <<‘More parental?’>>>” (TFv1 89). His desire to be able to “standard output his own thoughts” one day in order to “find some <<calculable>> sense” (TFv1 89) suggests a self-awareness of his digital interiority that is already calculating output in pseudo-programming language. As a webpage written in Javascript appears vastly different from the Javascript language that built it, this narrative strategy in Anwar’s chapters suggests that we are privy to the system of language within Anwar’s consciousness that produces and operates his more clear and controlled output. That is, inwardly, Anwar’s consciousness is erratic, distracted, formulaic and systematic, making constant digressions and jumps, sometimes physically across and down the page (TFv1 89), yet his output is clearly calculated, as exemplified by the dialogue he shares with Xanther and others.

Where typography actualizes character cyber-consciousness self-referentially, the “Narcons” maximize the novel’s metafictional qualities by interjecting the narrative that they, as digital entities, have a hand in producing. After declaring that this is “[a] good enough place to pause,” TF-Narcon9 explains that the Narcons are digital entities, “computer programs that have…written the novel”59 in, what appears to be, computer code or software (TFv1 565). Like the way in which Anwar’s narrative demonstrates a computer code input paired with a controlled and eloquent output, TF-Narcon9 demonstrates that the novel itself has an underlying “code” that is required for it to function, and the Narcons are, in part, responsible for this “code.” When TF-Narcon9 explains that the Narcons are “nothing but numbers. Zeros and ones” that “never run out…” (TFv1 565), it suggests that the Narcons constitute the digital machinery that has written the novel’s underlying code (cf. TFv1 568). TF-Narcon9’s explanation of the way in which the subset “embodiments” work gives us a demonstration of how this coding process works. It says: “For example TF-Narcon9X(Action/0510201408…00018749%) looks something like this: One early Saturday morning in May, Xanther went with her stepfather to see about a dog in Venice. It was raining hard” (TFv1 568). TF-Narcon9’s code and the segment, “One early Saturday morning…in Venice” mean the same thing, but they are fundamentally different in language as if operating from different sides of a machine.

The Narcons certainly present themselves as responsible for the novel’s code, but this digitality is composted with an involved, ironic postmodernist metafiction where the Narcons make reference to the novel’s constructed nature. The Narcons’ intervention is bookended by two large, black, slender rectangles that, together, create a “pause” symbol (TFv1 563, 578). This “pause” playfully suggests that the novel is taking on characteristics of other visual and digital media, but more importantly, the overt interjection by TF-Narcon9, speaking directly to the reader (TFv1 563–78), is a conspicuously postmodernist tactic—a metafictional (and even metanarrative) address where the text “self-consciously and systematically draws attention to its status as an artifact in order to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality,” and between narrative and reality.60 Many Narcon interjections throughout the novel are brief citations, dates, or corrections, while some quotations are quite opinionatedly directed at the reader. For instance, in Jingjing’s first chapter, “zhong,” after the first line of Mandarin appears, TF-Narcon9 interjects: “Really? Not your Google bitch” (TFv1 104), speaking directly to the (presumably non-Mandarin-speaking) reader and berating them for (very likely) glossing the Mandarin without translating. By pausing and intervening with the narrative, the Narcons draw attention to the novel’s artifice, and, as “Narrative Constructs,” they highlight the very constructed nature of the literary narrative.

Yet, what makes the Narcons’ meta behavior most striking is that they not only draw attention to the novel’s literary artifice, but also to their own status as metaphorical digital machinery, contributing to .compostmodernism’s re-use of postmodernist tenets within a digital context. The larger Narcon passage exposes the Narcons’ awareness of their status as literary components in keeping with postmodernist metafiction, but what indicates that Danielewski is reconfiguring this postmodernist tenet is the fact that TF-Narcon9 is also cognizant of its status as part of a digital system. Beyond blurring the line between “fiction and reality,”61 this digital self-awareness blurs the line between print and digitality, and the Narcons emerge as The Familiar’s cyber-consciousness, or cyber-self-consciousness. During the Narcon “pause” section, TF-Narcon9 outwardly indicates that “in terms of presentation, [it] is optimized to manage metanarrative gestures in modes presently recognizable as personal and colloquial, often inconsistent, sciolistic, and not necessarily reliant” before including a list of “subset voicings” that are different literary styles and movements such as postmodernist, modernist, postcolonialist, confessional, etc. TF-Narcon9’s optimization to manage “metanarrative gestures” (TFv1 566) is doubly self-conscious in that it is aware of its management of self-aware narratives at the same time as it is self-conscious of its status as narrative construct. The fact that this management is digitally optimized composts postmodernist metafiction and metanarrative with digitization, indicating that the Narcons are aware of their capabilities as digital machinery. Danielewski takes this digital self-awareness even further when TF-Narcon9 describes “Parameter 1” to the readers: “MetaNarcons Do Not Exist” (TFv1 573). TF-Narcon9 seems to be insisting that there is no such thing as a self-aware Narcon, but the statement proves ironic because while it condemns the existence of a Narcon that is aware of its identity as a Narcon, TF-Narcon9 has already introduced itself as a “Narrative Construct.”

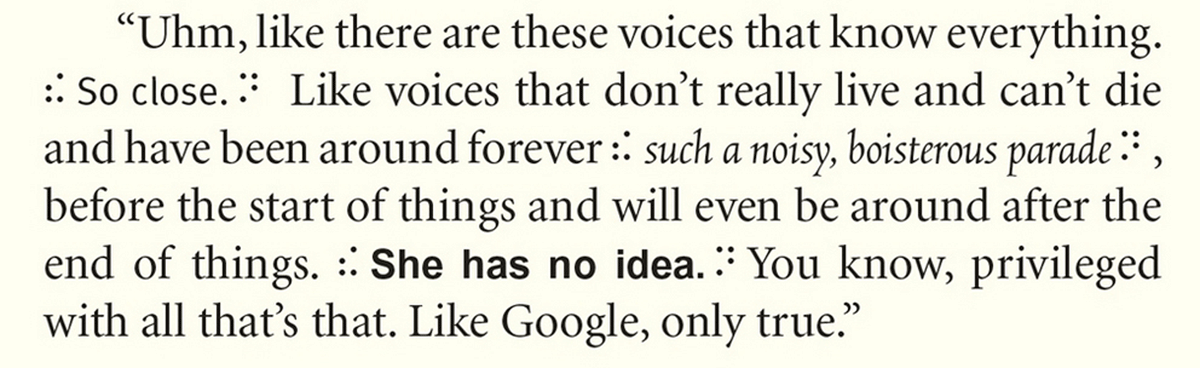

Because the Narcons are self-aware digital agents seemingly responsible for coding the narrative, and because the cyber-consciousness of each character in The Familiar occurs within this representation of a digitally rendered narrative, the Narcons emerge as the authors of character cyber-consciousness, and their interjections intensify this cyber-consciousness by overtly infiltrating it with their digital machinery. For instance, the Narcons increasingly shape Xanther’s cyber-consciousness in that she unknowingly becomes aware of them. During her appointment with her therapist, she asks, “Do you ever think, like, there’s a conversation going on, you know, like somewhere out there, somehow parallel to the one you’re having with yourself, like in your head, or even with someone else?” (TFv1 193). At first, it seems as though Xanther is asking the sort of questions a therapist would expect, but upon Dr. Potts’ prying, she elaborates:

The infinitude that accents her cyber-consciousness shows through with her remark that the voices in her head “know everything,” “have been around forever” and will continue to “be around after the end of things” (emphasis added) (TFv1 193). Her comparison between these voices and Google further highlights how her cyber-consciousness embodies an internet search engine. However, in this passage, the interjections of the Narcons are aggressively self-aware. This scene suggests that Xanther is at least subconsciously aware of the Narcons, and while she cannot necessarily interact with them, her remarking on them establishes that these programmed, digital entities are not only writing her cyber-consciousness on the level of the novel, but also communicating with her within the very cyber-consciousness that they have allegedly coded.

Machine Two: .Compostmodern Operation in The Familiar

Early in the novel, Anwar describes his game engine as “‘a metaphor” calling “the structure designed to contain, ignite, and harness that energy…requir[ing] many parts” (TFv1 85). He uses a car engine to explain this to Xanther, but when he insists that “[his] job is to esemplastically fashion a program which smoothly coordinates various parts in order to deliver a smoothly running vehicle” (TFv1 85), the narrative is self-consciously referring to the novel as this vehicle, fulfilling his original remark that the engine is metaphorical—a metaphor for The Familiar in which he is a character. This metaphorical “engine” is further explored when, after Xanther first hears the cat’s strange cries, she asks her father what “the gasoline” is in a game engine. Anwar’s inability to answer this paired with the close proximity between the question and the cat’s cries (represented by pink ellipses), suggest that the cat becomes the “gasoline” that makes this textual machine run (TFv1 463–64)—and as the series goes on, we find this to be true. But who operates The Familiar? On one hand, it might be logical to suggest the Narcons, as digital authors of character cyber-consciousness. On the other, Danielewski as author is the ultimate “operator,” potentially the Narcons’ Narcon. In another sense, we know that the Narcons “have been programmed by the mysterious VEM Corporation,” and because VEM is “an entity referenced in Danielewski’s previous novels,”62 it seems to hold some degree of narratological power over the work in hand. Yet, Lindsay Thomas also asserts that Danielewski’s “novels seem to push beyond the page” and “our responses to the novels are important to the meaning of the novels.”63 In .compostmodern machinery, the reader’s physical relationship to the text is a crucial part of an act of .compostmodern operation wherein typography and materiality are linked, and which expands on the reader’s relationship to the codex by including the reader’s engagement with digital media and the internet as part of this reading operation.

Both character cyber-consciousness and the Narcons’ metafictional infiltrations are visually actualized via experimental typography, but such typography demands that the reader enter into a physical relationship with the novel, instantiating the .compostmodern operation of the .compostmodern codex. Nathalie Aghoro argues for a similar process in House of Leaves, where “the cognitive reading experience becomes substantially palpable” and “reading becomes a material experience.”64 .Compostmodern operation notes a similarly material reading experience, where the materiality of the book is realized through typography, which necessitates the reader’s physical relationship to the codex. The Familiar’s materiality becomes focused through the demands set by its “marked”65 typographical illustrations of verbal signs because these signs are complexly arranged, requiring the reader to flip the novel, read backwards, refer back etc. The typography depicting Xanther’s raindrop cyber-consciousness challenges the reader to turn the book sideways, to magnify fine print and to read portions of the narrative nonlinearly, in a way that highlights The Familiar as akin to “literary works that strengthen, foreground, and thematize the connections between themselves as material artifacts and the imaginative realm of verbal/semiotic signifiers they instantiate.”66 The Narcon passage is central to the novel’s connection between typography and materiality because it functions as a reference section that inspires such material engagement in the reader. Most simply, within this section TF-Narcon9 upsets linearity by asking the reader to flip first to Parameter 3 (TFv1 565) and then to Parameter 2 (TFv1 193) out of numerical order before the Parameters are ever listed (TFv1 573–75), requiring the reader to physically engage with the novel non-uniformly. Beyond this, on a first read-through of The Familiar, the Narcon section will likely inspire the invested reader to return to the beginning of the novel to reconsider all previous Narcon interjections in the narrative for which they now have context. That is, just as House of Leaves exists as “an extensive hypertextual navigation system connecting multiple narratives and reading paths,”67 so too The Familiar constitutes a print manifestation of digital hyperlinks that requires the reader’s physical engagement with the codex. Like the internet “with its links, millions of pages and multiple reading paths,”68 The Familiar’s Narcon section offers a reference point for various nonlinear and fluid jumps and clicks in the reader. Even after the reader grasps the function of the Narcons, the complexity of the Narcons’ functions and capabilities draws the reader back to the Narcon section over and over again. Even beyond the Narcon section, the division of the novel into nine narratives focalizing nine separate character perspectives has inspired readings of The Familiar by character rather than by linear volume.69 While the Narcon section’s typographical experiment inspires ergodic reading wherein “the reader…explore[s] at will, get[s] lost, discover[s] secret paths, play[s] around” and “follow[s] the rules,”70 the way the Narcons as digital entities are what necessitate this physical exchange between reader and codex further exemplifies the .compostmodern codex as machine.

This physical relationship is always prompted by the typographical cyber-consciousness of the various characters, but the Narcons’ illustration via unique typographical “brackets” (TFv1 574) is a hypertextual arrangement that demands a material relationship between reader and .compostmodern codex. As I will demonstrate, along with the visual actualization of character cyber-consciousness through typography, Danielewski’s typographical arrangements of the Narcons as sporadic and dispersed imitate hyperlinks, establishing their digital machinery by requiring the reader to physically traverse intricate “paths” between chapters, character narratives and even volumes:71

This scene describing Xanther “cuddling” Redwood in TFv4 includes a link back to TFv1 when the breaths into his body are described as “finding the smallest way into the smallest place, where it should have stopped, at least found resistance” (TFv1 157). With this context, we are meant to understand their inextricability as one of life-force and biology. The cooling flame occurs every time she is reunited with Redwood, while she burns up with severe fevers the longer she is separated from him. The original scene in TFv1 occurs within the narrative, but the repetition of it in TFv4 suggests a sort of jumping back in Xanther’s interiority—her cyber-consciousness—as enacted by the link created by TF-Narcon27 as digital entity link in TFv4. But more importantly, the Narcons’ interjections in this scene animate the reader’s relationship with the codex, prompting him or her to physically go back to TFv1—a completely different volume—wherein we find TF-Narcon9 saying, “Only nothing was resisted” and TF-Narcon3 saying, “Nothing was refused” (TFv1 812–13). Because the Narcons are established in One Rainy Day in May as digital entities that have a certain degree of narratological power, these Narcon interjections that seemingly connect the distanced print volumes of The Familiar, emerge as figurative hyperlinks that illustrate The Familiar’s cyber-consciousness (or cyber-self-consciousness). Rather than a brief flip to another page within a volume or a footnote’s footnote, as we see in House of Leaves, TF-Narcon27’s “links” to other volumes and page ranges complicate the linear reading process far more aggressively, physically impacting the reader’s relationship to the codex—a set of five, separate, 800+-page volumes. Therein lies the irony at the heart of these Narcon interjections: while they imitate digital hyperlinks, they require the more arduous, physical engagement from the reader with the print codex, thus emphasizing the material importance of the book, or, to use Pressman’s phrase, catering to the “‘aesthetic of bookishness.’”72 As Pressman asserts, “bookishness” refers to “creative acts that engage the physicality of the book within a digital culture, in modes that may be sentimental, fetishistic, radical” and it “signifies a culture grappling with its own increasing digitization.”73 She calls House of Leaves a “bookishness novel that allegorizes fears of the digital and the power of paper-filled books to safeguard against changing times”74 suggesting that “the novel aestheticizes its bookish format in ways that prompt readers to recalibrate the role and value of the book within a digital, transmedial network.”75 The cross-volume links in The Familiar constitute a similar aestheticization of bookishness in the face of digitality that Pressman identifies in House of Leaves, but rather than allegorizing fears of digitality, this aestheticization of bookishness is crucial to .compostmodern operation.

Even more aggressive than TF-Narcon27’s links to previous volumes are those that direct the reader to volume five, Redwood, which was published last in the series. When one read Hades shortly after its publication, it was impossible to consult the unpublished fifth volume, which, in a sense, offered those readers of volume four a “dead” link to a target under construction:

One would think that this request by TF-Narcon27 to hyperlink to undisclosed pages of volume five means that when it finally is released, the reader must again re-read the preceding volumes in order to re-locate those now “active links” to the newest instalment of the series. However, even with the publication of Redwood, the redacted page numbers leave the Narcon hyperlinks dead and inaccessible, and TF-Narcon27 in Redwood does not refer back to these links. These links to other volumes never transcend season one, although they are only ever made by TF-Narcon27 whose “27”—much like TF-Narcon9 whose “9” implies, along with its listed “subsets” (TFv1 566–67) that it serves as narrative construct for the nine characters specifically—suggests that it serves as narrative construct for the twenty-seven volumes respectively. These hyperlinks provided by the TF-Narcon27 underline The Familiar’s digital machinery in that the “verbal signs” within dictate the reader’s physical relationship to the .compostmodern codex itself. Or, in the context of Hayles, the Narcons create a connection between the “verbal constructions” in narrative76 and the material existence of the novel as codex, and in so doing, signal to the .compostmodern thematic of infinitude in that the reader’s responsibility with the codex (as intricately hyperlinked to sometimes impossible “pages”) has no end in sight. This is even further exacerbated by the fact that The Familiar as we know it is currently “paused,” meaning the 22 unpublished volumes, whether they include references via Narcon links or not, remain inaccessible.

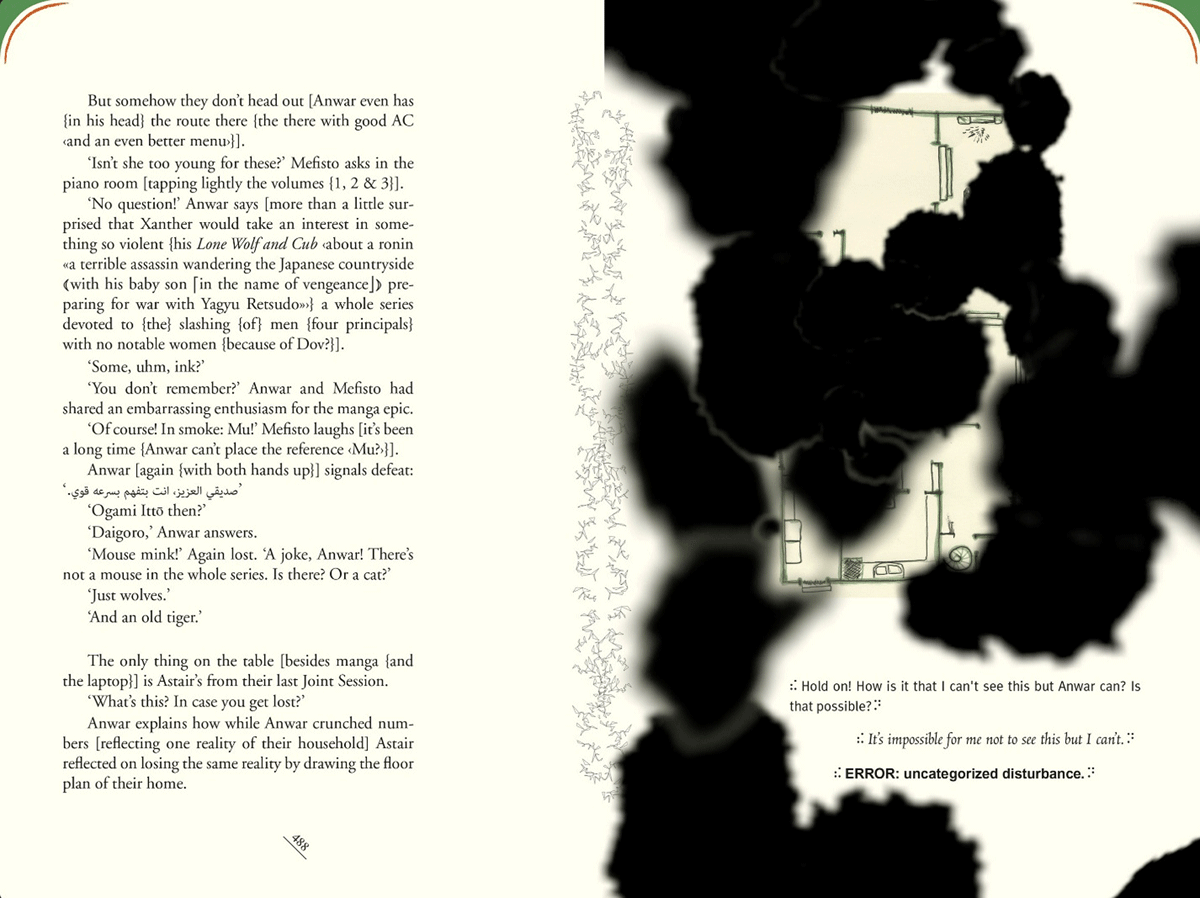

Just as the Narcons’ hypertextual “brackets” use typography to invite the reader to physically engage the codex by flipping to and from live and sometimes dead links between volumes, these links are used to indicate systematic errors, glitches, or “smudges” in the Narcon machinery. Recall how Xanther views her seizures as akin to to overload of information to the brain: TF-Narcon9 outwardly admits that it can sometimes “glitch” or “smudge” when it is overloaded with too much information or when it is “forced to address subjects not anticipated” (TFv1 566). The fact that the Narcons can “glitch” draws attention to their status as digital entities in that they can suffer a malfunction in the figurative “software” of this machinery. But the most central way that these glitches contribute to my suggestion that the Narcons instantiate a textual machinery in the narrative is that, when they do glitch, they disrupt and break down the narrative itself. In volume three, Honeysuckle and Pain, Anwar’s narrative is interrupted by the typographical manifestation of TF-Narcon9’s “smudging” whereby a map that he shows Mefisto is clouded by black smoke and TF-Narcon9 reacts by saying, “Hold on! How is it that I can’t see this but Anwar can? Is that possible?”, TF-Narcon3 adds, “It’s impossible for me not to see this but I can’t,” and TF-Narcon27 finalizes the glitch with: “ERROR: uncategorized disturbance” (TFv3 489).

The black clouds illustrate the digital “glitch” in the Narcons’ narrative, perhaps showing the reader what the Narcons see, or in this case, do not see. The page following this glitch lists nine expressions in non-English languages which all say “Warning: Open Door” (TFv3 490). A similar “smudge” or glitch occurs at the beginning of Hades where a grey collection of smoke bleeds into the text and TF-Narcon27 says: “Retrace COMPLETE,” “Remap COMPLETE,” and “Overwrite SUCCESSFUL” (TFv4 53), and then cites the three specific pages in the preceding volume wherein the retrace and remap were attempted, and the overwrite was inaugurated (TFv3 322, 453, 837). The essential breakdowns in Honeysuckle and Pain occur when Jingjing’s consciousness connects with TF-Narcon9’s (TFv3 453) and the three Narcons begin to interact in violation of their parameters (TFv3 837). Similar to Hayles’ technotext, which “interrogates the inscription technology that produces it,”7778 the .compostmodern novel is aware of its status as text—but that text identity is inherently digital. We can see, in these breakdowns, how the Narcons “mobiliz[e] reflexive loops between [the] imaginative world”79 of The Familiar and the material reality of the codex, thus warranting the reader’s physical and active engagement with the codex itself.

The reader’s physical relationship to the codex through typography highlights the novel’s .compostmodern textual machinery and marks the beginning of .compostmodern operation, but the complexities and nuances of The Familiar necessitate internet supplementation. In a basic sense, Danielewski peppers the novel with obscure and encyclopedic references to books, films, historical events, gang lingo and code that often warrant a Google search for context and reference. As mentioned, the Narcons establish that they are “[n]ot [the reader’s] Google bitch” (TFv1 104), a self-conscious reference to the reader’s impending reliance on the internet and other resources to make sense and meaning of The Familiar. It is a metafictional request (wherein the Narcon explicitly indicates the necessity of a Google search) that suggests the reader must do their own Googling and take on a digitally supplemented relationship with the text. What separates The Familiar as a .compostmodern novel from other encyclopedic novels of the twentieth century and prior, which also required searches for supplemental material albeit in analogue, is that the novel itself—via the Narcons—breaks the fourth wall in order to direct the reader, not only to supplement their reading, but also precisely how (digitally) to supplement their reading.

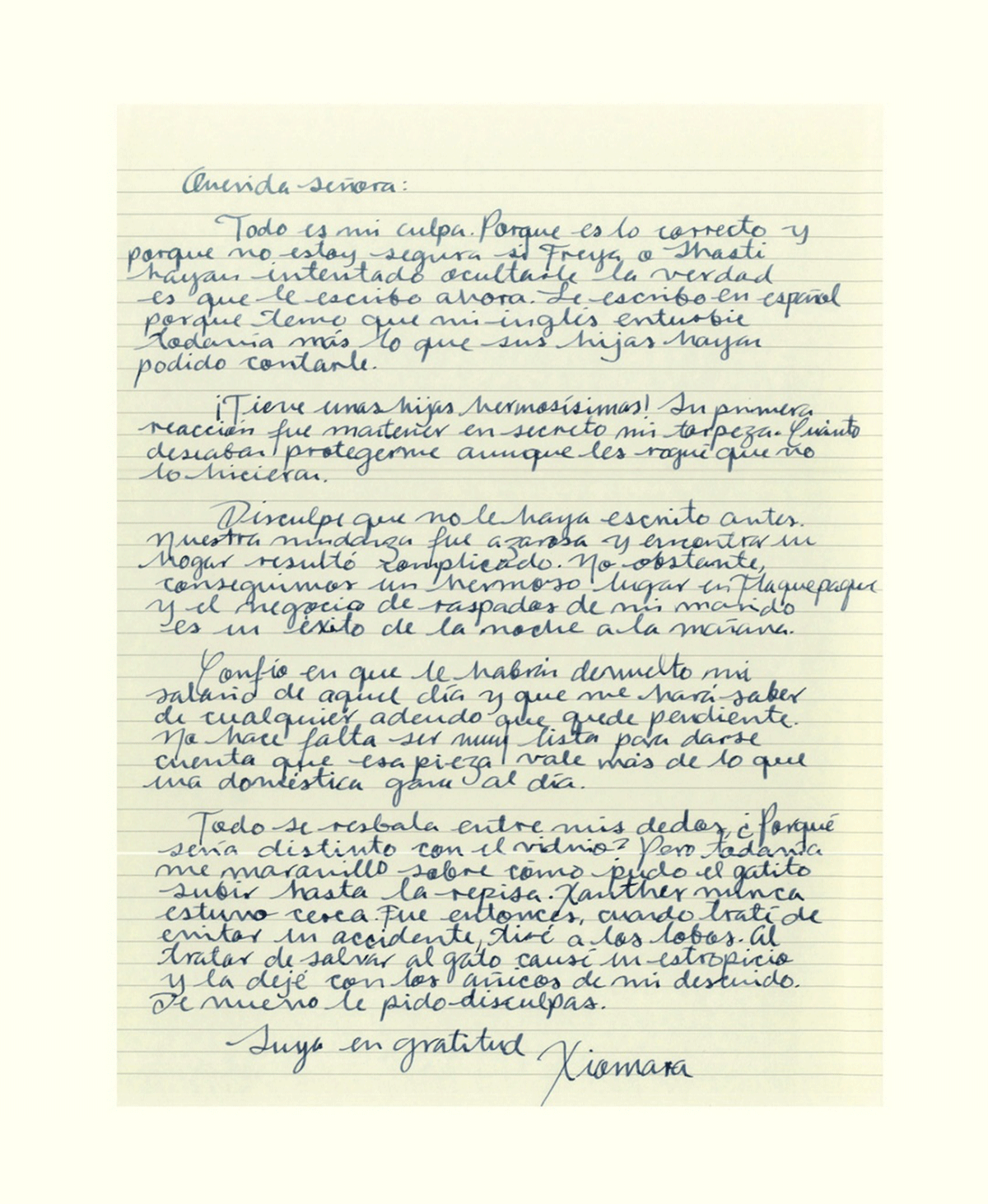

The difficulty of the novel does not end with Google searches, as long stretches of the novel appear in Armenian, German, Hebrew, Mandarin/Cantonese, Russian, and Turkish, left untranslated. Readers unable to speak these languages risk sacrificing information about an already complex novel if the passages are glossed, and again, the novel self-consciously pressures the reader to seek translations. For instance, when Xiomara resigns as the Ibrahim’s housekeeper, she leaves a hand-written note in Spanish:

Immediately following, the narrative indicates that “Astair doesn’t have time to even Google Translate it” (TFv3 598), although she wonders what the letter says. Again, the novel self-consciously and overtly signposts “Google Translate” as a means of hinting to the reader that they do have time to translate it, and should. Furthermore, the fact that the note is hand-written—which proves difficult to translate via the smartphone app—serves another layer of irony in that it not only insists on the materiality of Xiomara’s note, but it also insists that the reader type her letter out first in order to successfully Google Translate it.80 These necessary translations are consistent throughout the novel, and my own reading of The Familiar constitutes .compostmodern operation in that I often read with the Google Translate app on my phone, actively transforming words in other languages to English as I read, maintaining my physical relationship to the codex but supplementing this relationship with digital technology. An original passage reads as follows:

The following illustrates how the hand-held app uses the smartphone camera to automatically capture and translate the reading on the go, where the Mandarin in the top line is translated to English:

With the use of the hand-held Google Translate app, the .compostmodern operation is not only a physical engagement between reader and codex, but also between reader, codex and technological supplement. Yet, as mentioned above, translations via Google Translate are not always coherent, adding another layer of irony to this digital supplement process where the very technology the Narcons direct the readers to use fails in producing direct translation, potentially altering meaning.

In addition to the internet and software (as above) providing references and applications for obscure or unknown information, digital technology also supplements the reader’s parsing through of The Familiar’s own convoluted fictional universe by hosting online communities on platforms such as Wordpress, Reddit, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and MZD Forums, where readers share theories, deliberate over details, and offer close readings. The novel is shrouded in mystery, and the narrative is filled with minute details that subtly shape the larger plot, if the reader catches them. Consider the odd coincidence of Cas identifying as Hopi in Into the Forest (cf. TFv2 556) when, at the close of One Rainy Day in May, Luther murders his new recruit named Hopi. Similarly, the three “tattooed <Hispanic types <<Latino?>>>}” who are described as laughing outside of the pet shelter following Xanther’s freeing of the caged animals could be any members of Luther’s gang (TFv2 530). The novel releases this information mysteriously and because online communities for The Familiar create digital spaces for the obsessive reader to deliberate what are essentially “glitches” in The Familiar’s matrix, these details can invite the reader online to make sense of the elusive and secretive meanings within a social, online community. Aghoro writes that one of the crucial benefits of the “reading communities on the MZD Forum” is that they render “the individual effort to solve the riddles of House of Leaves” a “social activity.”81 Yes, these online communities turn away from the “sedate and solitary activity” that reading has long since been perceived to be,82 but it is not only the community-building nature of the online forums that stands out; rather, it is the “effort to solve the riddles.”83 The kinds of “riddles” rampant throughout House of Leaves are similarly woven into the fabric of The Familiar, and these online communities offer a space within which readers can guess, theorize, debate and imagine.

For instance, all of Danielewski’s publications are connected by VEM™ or, the VEM™ Corporation. Although readers continue to debate just what VEM™ is, VEM™ might account for what Thomas calls the intertextual “living link that connects” Danielewski’s oeuvre.84 Like House of Leaves, for instance, Danielewski’s 2012 short story “Clip 4” reads as an academic article written by Realic S. Tarnen.85 The interconnectedness of “Clip 4” and The Familiar plainly situates the two pieces within the same fictional universe: “Clip 4” describes the gruesome death of Realic that is referenced in The Familiar, and it provides further context for the Orb “Clips” that Cas scries (TFv1 629–33) which, in turn, provide context for “Clip 4” as Audra’s death appears as “Clip 1” in One Rainy Day in May (TFv1 633). But more importantly, it is the mysterious nature of the short story, accessible online via links disassociated with Danielewski’s official website, that remains pertinent. At one point, Danielewski offered a link to “Clip 4” from his site, but it proved to be a dead link, taking the user to a Goodreads review of the story—ironic, considering the opening of “Clip 4” includes Zeke Rilvergaile relating that “Links are broken.”86 Danielewski’s “Parable #8: Z is for Zoo” and “Parable #9: The Hopeless Animal and the End of Nature” remain similarly difficult to locate. Danielewski also uploads digital supplementary material online in a way that contributes to .compostmodern operation by making researchers out of the readers, blurring the line between fiction and reality. For instance, he has woven riddles into his Instagram account on which he has posted geographical coordinates87 that readers worked tirelessly to contextualize with the novel.88 He also facilitated and promoted a “day of entanglement”89 on Instagram that involved readers interacting with nine Instagram accounts (one for each character in The Familiar) in order to solve certain riddles associated with The Familiar universe via internet rabbit holes. With this, it seems that he purposively included supplementary material to The Familiar on the internet as a means of provoking the reader’s interactivity in the digital space. Such mysteries compel the reader to commit a degree of internet sleuthing in an attempt to satiate the intense desire for knowledge about The Familiar, the Clips, VEM™ and the Orb—with which Danielewski is extremely provisional. Little academic criticism exists on The Familiar and the aforementioned short stories, yet the cruel joke lies in the fact that these stories themselves are presented as if they are academic articles—“mockademic,” as I like to call them. Presenting them this way, Danielewski creates what Kirby would call an “apparently real”90 environment for The Familiar online, while simultaneously parodying academic scholarship.

The most eerie example of the “apparently real” is the website parcelthoughts.com, a fictional social media site used by Xanther and others in The Familiar and referenced in “Clip 4,” but one I found to exist online. The site now links to Danielewski’s website, but for quite some time, it existed as its own site, featuring the same Parcel Thoughts logo and aesthetic seen in The Familiar (TFv1 334). The site appeared quite like Realic describes it in “Clip 4”: “a directNIC This-Domain-Is-Under-Construction page. There [are] no introductions or explanations.”91 Although the site was never explicitly under construction, its defunct nature—it was merely functionless despite readers’ attempts to read its code92—grounded the reader’s experience of Parcel Thoughts on the internet, connecting it to MZD’s The Familiar universe wherein Realic made the same internet voyage. The real existence of parcelthoughts.com, even if only for a time, could have prompted readers to search for Anwar’s Paradise Open or any of the Clips online—but none can be found. However, if Danielewski were to release any of these digital materials in some form, it would immediately alter The Familiar and call for new readings and interventions. Danielewski plays with the “reality” of The Familiar’s universe avidly—Danielewski himself appears in Hades enjoying a drink at “bluewhale” while observed by Özgür. The Narcons censor the name and identity of this mysterious man “wearing a fedora,” but I argue that it is undoubtedly Danielewski, given in photos and interviews—and even his author’s photograph on his website—he is frequently seen wearing his signature fedora.93 This interconnective intertextuality similarly has its roots in postmodern intertextuality and style, but because the intertexts are supplementary, “mockademic” works associated with The Familiar universe, and because so many readers now access them online, The Familiar undertakes the .compostmodern act of bringing together, breaking down and reconfiguring postmodernism and new (modernist) sincerity with the digital. Such a reading experience makes a digital researcher out of the reader, necessitating the reader’s use of the internet in a way that transcends the .compostmodern codex.

The online communities create a system wherein the internet supplements a reader’s engagement with The Familiar, sometimes going so far as to blur the boundary between fiction and reality. But each supplementation is always also another reader’s written supplement. In other words, the crucial byproduct of this .compostmodern operation is that it opens up the reader’s role as contributory “author” or theorist of the text. The online reading communities for The Familiar intensify the reader’s interactive role and actually “permit the reader…to intervene textually, physically to make text” and “shape narrative development,” as Kirby writes of the digimodernist text,94 in that the readers share their theorizations of the novels, in textual format online. Yet, unlike a digimodernist text, The Familiar does not overtly invite readers to author the narrative or “edit” physical text as it unfolds in real time; instead, the reader’s “authorship” is one of parsing meaning in online digital environments. Much of the productive discourse on The Familiar is published on these online forums, some of which have been cited95 in critical work on Danielewski.96 Similarly, Sascha Pöhlmann includes the fan forums as viable avenues for critical response that, alongside academic publications, are yet to exhaust the “critical possibilities” of Danielewski’s novels:

Given his importance as a writer and the fascination of so many readers with his work, it may seem surprising that academic literary studies have taken a while to engage it critically on a larger scale. While there is an ever-active forum on the Internet in which fans debate his work with a fervor and love of detail only known from Pynchonites and Joyceans, academic criticism has mostly been limited to individual papers and essays published by enthusiasts in different journals.”97

Because academic criticism of The Familiar has been so scant, the online forums discussing his work emerge as enriching resources for academics and fans alike. Danielewski first uploaded House of Leaves online in 1997 as a PDF in order to share his work in progress with friends, and just before its print release in 2000, he shared the novel online serially.98 By hosting his first major publication on the internet in this way, allowing for a community to read it, Danielewski quite crucially and deliberately created a digital framework for the engagement with and reception of his literary works. Danielewski quite actively uses digital media to communicate with readers in a way that differs from the typical author’s promotion of their work via social media. Whether it is to commend their posts on social media99 or to request photographs of readers’ cats to be included in impending volumes,100 Danielewski has proven involved in the digital community surrounding his oeuvre. Appropriately, Danielewski promotes and maintains the digital environment of The Familiar through an active and engaged social media presence on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, even going so far as to host “The Familiar (Volumes 1–5) Reading Club” on Facebook, for which, leading up to the October 31, 2017 release of Redwood, fans and scholars of Danielewski came together for an online discussion of The Familiar series unfolding in real time. Danielewski is also known to make “visits” to these social media reading groups, which further highlights the unique way in which digital spaces have facilitated his reading communities since the earliest inception of House of Leaves.

Conclusion

In Big Books in Times of Big Data (2019), on the subject of the death of the novel, Inge van de Ven suggests that looking at “the novel’s continuous death and rebirth” will aid us in “understand[ing] the present insistence, by many prominent novelists and book artists, on scale” as “time and again, the novel survives its own ‘death’ by adapting to [technological] changes.”101 While van de Ven identifies “trends of size and scale in the novel” as playing an active role in this “death and rebirth,” particularly in the ways “monumental” works such as Danielewski’s The Familiar respond to “the newer materialities of the digital,”102 I have outlined .compostmodern textual machinery as that which accounts for The Familiar’s demonstrative rebirth of the novel in an increasingly digital age. Van de Ven argues that “this twenty-first-century trend towards magnitude” is both “a gesture of resistance on the part of the print novel in the face of the book’s expected demise due to datafiction” as well as “the expected outcome of this development.”103 Yet, there is something to be said of van de Ven’s assessment of The Familiar’s readership as akin to that of “‘Quality TV’” which she defines as “a genre that caters to a desired audience that is considered ‘valuable,’ educated, and affluent, with sufficient disposable income to attract advertisers.”104 The Familiar, which Danielewski has divided into “Seasons” and “Episodes” much like a TV series, was put on “pause” on February 2nd, 2018 because, “[u]nfortunately, [Danielewski] must agree with Pantheon that for now the number of readers is not sufficient to justify the cost of continuing.”105 Remarking on The Familiar’s magnitude and complexity, van de Ven writes: “This high demand on readers’ skills makes The Familiar an informative, albeit failed, experiment about to what extent an audience can be seduced to devote time to challenging and experimental serialized literature within an attention economy.”106 It is true that “after having read (part of) One Rainy Day in May, some of Danielewski’s readers and reviewers express a…sense of frustration,” stating “that they gave up on The Familiar after this first volume, complaining of its lack of coherence.”107 However, the novel’s hiatus has been equally frustrating for those who have followed its volumes diligently, and many hold out hope for the day Danielewski (or Pantheon) presses “play” again. As van de Ven suggests, The Familiar “offer[s its] fans opportunities to become involved in such a transmedial story world through fan participation, e.g. on social media,” “necessitat[ing]” what Henry Jenkins calls “collective intelligence” wherein “‘consumption has become a collective process’” that often takes place amongst fans online.108 While van de Ven insists that Danielewski’s aim with The Familiar “has not exactly played out as hoped,”109 I view this “collective intelligence,” or rather, the novel’s “.compostmodern machinery” as that which continues to hum despite the inactivity at the publishing house. As the first volumes stand, the experimental typography within The Familiar continues to actualize character cyber-consciousness, necessitating a physical relationship between reader and .compostmodern codex. But as a means of transcending that codex, The Familiar, along with selections from Danielewski’s larger oeuvre, continue to inspire in online reading groups on Facebook, despite the novel’s “pause,” and avid readers have taken it upon themselves to animate Danielewski’s characters via fictional Instagram accounts that others can interact with and connect with online, all of which contributes to the novel’s abstract machinery. It is less that The Familiar’s “readerly collectivity” is “built on the value and cultural capital ascribed to these ‘elite’ audiences and their commodification in an attention economy”110 and more that this audience’s incessant effort to deduce meaning in online spaces mobilizes the .compostmodern machine beyond the tome.

In Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, Oedipa Maas becomes an accessory of the postmodernist author, doomed to flounder in a sea of potentially useful clues and led down the rabbit hole, decoding the function and aims of Tristero. In the final pages of the novel, Mike Fallopian puts the question to her: “Has it ever occurred to you, Oedipa, that somebody’s putting you on? That this is all a hoax, maybe something Inverarity set up before he died?”111 She is aware of this, even going so far as to reflect that either she has “stumbled…onto a secret richness and concealed density of dream,” or “[she is] fantasying some such plot, in which case [she is] a nut.”112 The unresolved nature of The Crying of Lot 49’s ending is frustrating to the reader: the unknowing is torturous. Yet, as we come to find, this is the very nature of postmodern paranoia and conspiracy: “truth” is arbitrary and meaningless, perhaps even impossible. To use Pynchon’s novel metaphorically, in The Familiar, Danielewski is Inverarity, and the reader is Oedipa Maas. Like Oedipa, the reader is catapulted through a labyrinth of wonder, questions, and uncertainty that has no foreseeable end: “a plot has been mounted against you.”113 However, herein lies the subtle quirk of .compostmodern operation that differentiates it from postmodern paranoia and conspiracy. While the character remained the author’s accessory in the postmodernist novel, traversing the labyrinthian “plots” set before her, the reader remains the accessory of the author in the .compostmodern novel, not traversing, but operating the .compostmodern codex sometimes with dis-ease, on paper, in theory and into the infinite possibilities of cyberspace.

Notes

- Robert Kelly, “Home Sweet Hole,” The New York Times, March 26, 2000. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/00/03/26/reviews/000326.26kellyt.html?_r=2&oref=login&oref=slogin (Accessed April 12, 2021). [^]

- Sebastian Huber, “‘A House of One’s Own’: House of Leaves as a Modernist Text,” in Revolutionary Leaves: The Fiction of Mark Z. Danielewski, ed. Sascha Pöhlmann (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012), 123. [^]

- Jeffrey Nealon, “Preface: Why Post-Postmodernism?” in Post-postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Just-In-Time Capitalism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), ix. [^]

- Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker, “Notes on Metamodernism” in Supplanting the Postmodern: An Anthology of Writings on the Arts and Culture of the Early 21st Century, ed. David Rudrum and Nicholas Starvis (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 310. [^]

- Robert McLaughlin, “After the Revolution: US Postmodernism in the Twenty-First Century,” Narrative 21, no. 3 (2013): 285. [^]

- Sebastian Huber, “‘A House of One’s Own’: House of Leaves as a Modernist Text,” in Revolutionary Leaves: The Fiction of Mark Z. Danielewski, ed. Sascha Pöhlmann (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012), 124. [^]