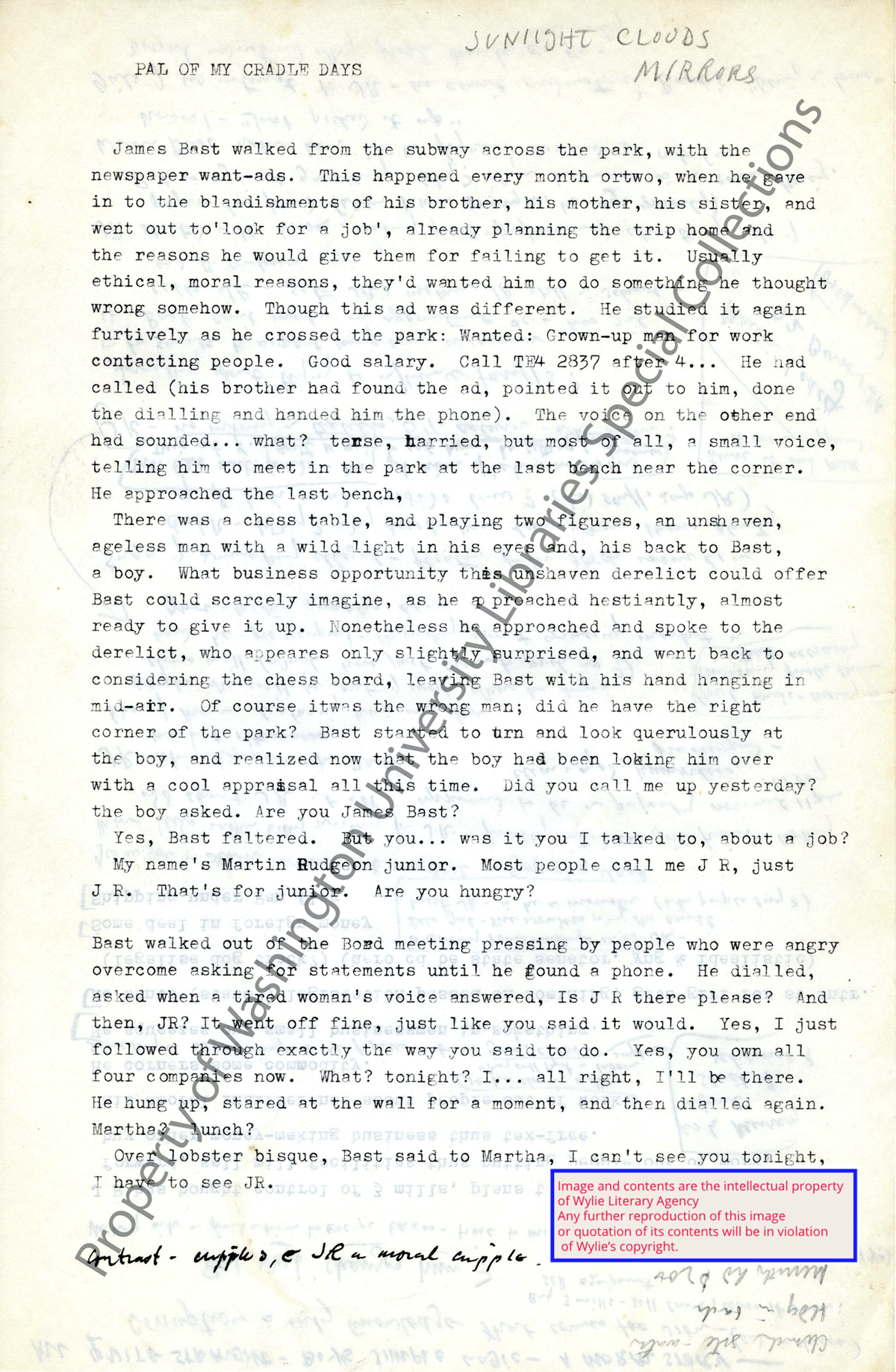

Composed primarily of unattributed, overlapping dialogue, moving from scene to scene through passages of unblinking visual narration, the defining formal quality of William Gaddis’ J R (1975) is a negative one: the complete absence of narrated thought. J R’s formal distinctions from its predecessor The Recognitions (1955) are so fundamental, and so widely understood as inseparable from its concern with life under corporate capitalism, that it may come as a surprise that they were not originary: Gaddis’ early drafts towards the novel were in conventional psycho-narration.1 See, for example, this draft (Figure 1) of the first encounter between protagonist Edward Bast (here called James, his father’s name in the final novel) and JR, the 11-year-old business prodigy who draws him into his dealings.2

Psychological activity here—that which Bast “realized now,” was “already planning,” or “could scarcely imagine”3—is linearly described in a prose that we could mistake for EM Forster on his Leonard Bast. What, then, might have prompted Gaddis’ invention of a thoughtless style? While the conventional-prose drafts are undated, they must come from the period between 1957, when Gaddis briefly started work on J R, and 1964, when, having resumed work in 1963, he first starts referring to his protagonist as “Edward” in correspondence.4 Between 1964 and the publication of the first thoughtless-style section of J R in 1970, Gaddis’ career as a corporate writer consumed most of his compositional energy.5 Working primarily at Eastman-Kodak and IBM, on issues from marketing to world economics to the corporations’ internal logistics, Gaddis was primarily an uncredited speechwriter but also created marketing and training material in a variety of media. This work, I’ll suggest, helped generate the novel’s innovations.

Elsewhere in this issue of Orbit, I’ve made the archival case for reading J R in closer relation to Gaddis’ corporate career than either he or his critics have previously encouraged.6 Joseph Tabbi speculated as long ago as 1989 that “it is even conceivable that, rather than simply depleting his literary energies, Gaddis’ corporate experience provided a technical training of sorts for JR.”7 I here pursue this line of inquiry, showing how the imperatives and procedures of Gaddis’ corporate work conditioned his fictive technique. While Tabbi suggests only that anonymous speechwriting must have given Gaddis fluency with ventriloquy and jargon, I’ll show that the corporate career offered both a mechanical training in various forms of non-psycho-narrative composition, and a rhetorical training in arguing about ideas central to J R’s world and form.

I’ll focus particularly on the concept of friction, which is not only a practical question for Gaddis’ corporate work, but also—as that work throws into new relief—a central theme and stylistic principle in J R. The novel’s dual concern with the vanishing of thought and with an economy in which commodities exist in a permanent state of exchange has led critics to characterize its stylistic construction in terms of the synergic relation between “flatness” and “flow.” These terms come from theories of economic transition, in particular the shift from an economics of psychology, regimentation, and efficiency to one of proliferation, liquidity, and commodification that theorists of postmodernity like David Harvey and Frederic Jameson have linked to the US economy’s tribulations of 1973. J R’s stylistic flatness and flow, on this account, engage its culture by reflecting money’s increasing departure from material embodiment, the increasingly fast and global processes of capital exchange, and the correspondingly supra-human forms of systemic and networked agency that impel such an economy. Whether from this political-economy angle that sees the novel either mimicking postmodernity or prophesying neoliberalism, or through a concern with posthuman forms of depthless subjectivity—be they poststructural or systems-theoretical—critics have usually treated J R’s registering of such shifts as the limits of its form and rhetoric.

What all these approaches share is reliance on a constellation of heuristics that constructs a space only “friction” could fill. When Gaddis himself was asked “If your work could have a positive social/political effect, what would you want it to be?” he replied, “Obviously quite the opposite of what the work portrays.”8 Critics seeking an optimistic rhetoric to J R have looked almost exclusively to flatness’ opposite rather than flow’s, seeking post-psychological versions of the “depth” the novel’s style seems to eradicate.9 If flatness and flow correspond horizontally as the novel’s “portrayed” givens, while flatness and depth make an oppositional vertical dichotomy, then they create a conceptual rectangle missing a corner.

| J R’s explicit form | Flatness | Flow |

|---|---|---|

| “positive… effect” – “the opposite of what the work portrays” |

Depth (addressed in criticism) |

? (unaddressed in criticism) |

What in this structure should correspond horizontally with depth, at the unportrayed “resistance” level? The answer should be flow’s conceptual antipode: friction, which has its own relationship to resistance.

Gaddis’ corporate work was constantly concerned with problems of friction and flow: it required him to frame commercial innovation in anti-frictive terms, to resolve frictions of coordination between his employers’ departments, to remove signs of ideological friction from prose he assembled from disparate sources. In what follows, I show how thematic and formal concerns in Gaddis’ corporate writing warrant a redescription of J R’s stylistic rhetoric. My central claim will be that what Gaddis’ corporate writing trained him to remove, his fictive form sought to restore: J R’s methods of implication reverse the polarities of his corporate composition to achieve frictions within initial terms of unidirectional stylistic and ideological flow. Furthermore, as those initial formal postulates rely on removing represented thought, so J R’s achievements of friction recuperate a place for unvocalized thought in a world that seemed to have done away with it. Since the friction-and-depth alternatives in J R cultivate aspects of traditional subjectivity, my Gaddis neither neutrally registers nor enthusiastically propounds a post-psychological world. I aim less to resolve existing disagreements about his prophetic supra-humanism or belated humanism,10 though, than to offer an archivally-warranted elaboration of the many modes of sentence-level stylistic implication in a novel whose innovative form is too often discussed in monolithic terms. Precision about the form should set future discussions of the overall rhetoric on firmer ground, and in the paper’s final section I show how formal shifts throughout the novel organize a constructive rhetorical arc rather than a “flat” mimesis. Whether in sentences or events, the achievement of societal friction and the recuperation of psychological depth are covalent throughout J R, and Gaddis’ corporate work helps us understand both why and—technically, stylistically—how.

The Friction Problem

J R’s most fully developed writer-character, Jack Gibbs, says at one point that “that’s what any book worth reading’s about, problem solving.”11 While prior critics have concurred that J R’s formal problems concern how to mimic or challenge those “postmodern” economic conditions of flatness and flow, the novel and its characters seem equally preoccupied by friction, particularly at its most self-reflexive moments.

Near the end of the novel, a character reads from a press release about “Frigicom” technology that can freeze sound in physical chunks: it “has attracted the interest of the recording industry due to the complete absence of friction associated with conventional transcription” (674). Since J R’s own formal technology rejects the novelistic convention of transcribed thought, Frigicom links friction to thought as the “absent” categories of J R’s world. Existing criticism treats J R’s nigh-exclusive transcription of instrumental dialogue as a new novelistic “technology” for the diagnosis of postmodernity’s defining flatness and flow. But the Frigicom advert’s insistence on friction’s “absence” puts “friction” on the page, and repeated implications that Frigicom is a fraud suggest that “complete”ly eliminating friction might be harder than advertized. J R’s stylistic “problem,” the project it suggests makes it “worth reading,” is not just how to represent a world of thoughtless flow, but how to recuperate thought and friction within that world’s givens. The corporate work, like J R, constantly frames its own practical problems in these terms of friction and thought, and it too gestures toward such recuperation.

In a speech he wrote for an Eastman Kodak executive, Gaddis implores product-designers to “seek[] the inefficiency”:12 profit relies on identifying and removing friction-problems that customers don’t yet know they’re hampered by. Friction-removal becomes commerce’s basic product. This anti-frictive discourse and ideology was Gaddis’ daily atmosphere for almost a decade of J R’s gestation. Yet the document that best illuminates the novel—tellingly, the only document he produced for Eastman Kodak under his own name—was one addressed inward, at solving friction-problems of the company’s own operation.

The supervisor who commissioned “Some Observations on Problems Facing Eastman Kodak’s Advertising Distribution Department” tells Gaddis that company executives were in “total agreement with the contents.”13 Gaddis’ popular proposals were a matter of friction-reduction: the problem, he identified, was that both “customers and EK people alike” were failing “to follow the prescribed routines which the system is designed to handle, thereby interrupting its smooth functioning.”14 “Smooth”’s joint implication of flatness and flow establishes both the kind of “functioning” Gaddis needed to perfect, and its incompatibility with the friction caused by human actors and their psychological categories (the document demands more constraints on “request” and “creation”).15 In the executive speech, friction-removal is a discoverable opportunity. In the internal report, it’s a maintenance necessity. Gaddis’ experience ventriloquizing about the one as Kodak trained him to address the other for Kodak. Yet writing about how to constrain human unpredictability to “the prescribed routines” leads him to imply that some psychological categories—the work of “decision” or “planning,” the exercise of “human judgment”16—are ineliminable necessities even in the pursuit of commercial efficiency. Gaddis thus finally suggests that the corporation’s own efficiency-goals would be best served by more friction and less flow: “corporate marketing” were demanding indiscriminate sending of more and more material to more and more outlets for whom it was less and less relevant: by the time Gaddis spoke to the distributing department, he found only “frank expressions of despair over the futility of trying to stop the flow of such material.”17 The tension between chaotic proliferation, total “smooth functioning,” and regulative “judgment” is a tension between flow and friction, and it animates J R’s narrative drama.

In two set-piece conversations that bookend their business relationship, for example, Bast and JR reverse roles in relation to the word “stop.” On the first occasion, JR—like corporate marketing against the distribution division—overflows Bast’s pleading to “stop, just stop for a minute! This whole thing has to stop somewhere don’t you understand that?” by blithely enthusing about a “neat tax loss carryforward” (my italics, 298). But 350 pages later, it’s JR who pleads to Bast, “How am I supposed to stop everything?” (647). This switch describes the novel’s main rhetorical arc. While total flatness and flow is the novel’s starting point, both Bast, at the outset of JR’s empire, and JR himself, when it starts to collapse, seek frictive alternatives to its seeming inevitability. It’s on this axis that I’ll argue the novel’s central set of “problems” get framed and, eventually, tentatively, resolved.

So why haven’t previous J R critics discussed friction, and what else has that led them to ignore? They have stressed (often exclusively) the preponderance of unattributed dialogue,18 then characterized the overall reading experience in terms first of an unbroken “flow” of information, and of an overall “flatness” following from the absence of authorial indications about that information’s relative salience. Frederick Karl established these basic terms within a few years of J R’s publication, suggesting that, stylistically, “the goal is seamlessness and flow” to ratify the tendency of the novel’s events: “Once caught in JR’s international money schemes, the characters have no lives except what the flow determines.”19 Subsequent critics have been less interested in the style’s correspondence with characters’ experience than in systemic mimesis, as in Tom LeClair’s comparison of J R and The Recognitions: in J R Gaddis “presses ‘flatness’ to a breathtaking extremity, shows that the deadly sameness Wyatt [Gwyon, Recognitions protagonist] found in pedestrian writing is now the rule of life in general.”20 LeClair’s “now” suggests that the stylistic difference between the two novels is a matter of both the changes in “the rule of life” in the 20-year interval between them, and of Gaddis’ increasing mastery of stylistic means for imitating that world. Joseph Tabbi reconciles character and system in suggesting that flatness and flow delimit the “transformation of subjectivity within the terms of an emergent world-system,” thereby “replacing a realism based on characters and interiority with a verbal and textual exposition based on systems.”21 Overtly non-mimetic readers preserve the flatness/flow heuristic even more totally: for Michael Clune, J R abandons the distinction, necessary in our world, between thinking and sorting—“individual attention and underlying system”—to investigate a hypothetical in which, since “success depends on an incapacity to think, or even to perceive, outside the picture of the world presented by price,” “[p]rice can replace intersubjectivity.”22 And Michael Levine finds J R a merely ludic artefact, to be read without “seeing in its… seamlessness some purpose other than an author’s will to work within an outrageous self-imposed constraint.”23 However these critics disagree, they concur that J R represents only flatness and flow, a “world-system” without friction, depth, or their associated psychological categories.

How, then, to derive criticism, let alone a program of “resistance,” from the novel’s mere matching of the economy in which it circulates? Nicholas Spencer explains what Gaddis’ suggestion that we locate his rhetorical implications in “the opposite of what the work portrays” has meant to most critics: “Instead of being simply mimetic, J R literally mirrors the attributes of postmodernity to produce a critical mimesis.”24 In LeClair’s comparative terms, its success is that it “more radically documents what it hates” than comparable fictions.25 In a recent discussion of how understandings of “Capitalist Realism”—the post-postmodern acknowledgement that capitalism circumscribes the imaginable—can be “informed by the literary,” Alison Shonkwiler and Leigh Clare La Berge suggest that imagining beyond Capitalist-Realist terms will only become possible once the constraints of its “representational dimensions” are “measured or identified.”26 J R, “identifying” both an economic structure and the representational practices by which it naturalizes itself, could thus do the basic resistance-work of demystification. Yet this necessarily limits J R’s stylistic rhetoric to epitomizing that which it wants to resist. This rules out in advance Gaddis’ actually representing any alternative. It’s this I want to dispute by stressing the novel’s articulations of friction.

Marc Chénetier alone associates the novel’s posited alternatives with a corresponding style. Rejecting the “726 pages of voices” approach on which “flatness” accounts rest,27 Chénetier points out that almost 100 pages of the novel take the form of visually-oriented narration: “Gaddis filigrees himself” through his language in these “islets of resistance to all systems,” setting authorial articulation against the flattening of language in the novel’s decadent dialogue.28 For Chénetier, the “narrative segments are the locus of literary stakes,” stakes understood and valued in terms of depth: of authorial presence, of the solid narrated world underlying the ephemerality of dialogue, and, in his own econo-mimetic reading, of a defence of “life perceived as permanent flow, as unassailable by utilitarian, exploitative, discursive patterns” (even this well-supported critique of the flatness heuristic ends up propounding flow).29 If Chénetier’s revision of thirty years of criticism shows us how J R might actively represent depth, then might the novel represent friction too? This is J R criticism’s own friction-problem: how frictive resistance might be figured, and what it has to do with the relevant depths—psychological work, authorial implication, alternative meanings. The corporate archive’s record of Gaddis’ routine work on problems of human friction offers some clues.

**

Gaddis’ clearest expression of the mindset that treats human psychology as undesirable friction comes in an ironic aside in a speech he wrote after “Some Observations…”: to “make product planning and marketing a sound, respectable science… the first thing would be to get rid of those variables—especially that last one, the unpredictable human customer at the point of sale.”30 Much of J R’s drama stems from the protagonists’ perspective on corporate systems’ tendency to constrain and rationalize human unpredictability toward pre-punched models, but the ventriloquous corporate work regarded the problem through the other end of the telescope. In “Some Observations…”, arguing in his own voice, he starts to develop the ambivalent insights that J R subsequently foregrounds.

The ambivalence arises precisely because “Some Observations…” sets out the anti-frictive, anti-psychological worldview with such practical specificity. Human unpredictability causes the Kodak system’s problems, particularly through what Gaddis considers the ill-advised offer to “tailor” products for individual clients. Noting failures “to follow the prescribed routines which the system is designed to handle,” he suggests that the humans involved needed to realize that “such a system demands orders tailored to the system itself.”31 He thus recommends lesser tolerance for clients’ “special and unreasonable requests,” and greater, more localized “exercise of coordination and control over creation of future items.”32 That which doesn’t fit the system is not only “unpredictable,” as in the speeches, but “unreasonable.”33 As “reason” opposes “human,” “requests,” and “creation,” so to be reasonable is to “follow the prescribed routines,” to “tailor” oneself to the system, to give “creation” over to “control.” Here Gaddis propounds the logic Shonkwiler and La Berge see as distinctive to neoliberalism: “Whenever ‘realism’ is defined as that which is measurable within a system of capitalist equivalence, then everything not measurable according to this standard becomes, by simple definition, unaffordable and unrealistic.”34 Recall Recktall Brown, The Recognitions’ avatar of capitalist control, and his mantra that “Business is cooperation with reality.”35 Yet, as I’ll argue J R goes beyond mere identification to represent alternatives, so “Some Observations…”—unlike the speeches—pushes its thinking far enough to undermine its own anti-frictive, anti-psychological impetus.

It particularly stresses the risks of treating systems as ends in themselves. When it comes to attributing agency in relation to supra-human systems, for example, Gaddis’ language veers between two poles: if blame falls on “[t]he failure of many of those using [the system’]s services,”36 then the system is still the grammatical subject of its own limited capacities of accommodation: it “demands orders tailored to… itself,” such that “[l]ike most systems, this one leaves little room for exceptional demands to be made upon it.”37 It demands, in other words, but can’t take being demanded of. The language in which Gaddis pinpoints this problem matches J R’s interest in the conflict between individual and system: “[s]pecial handling means human judgment, and in Advertising Distribution this means time and expensive talent which is too often called upon simply to keep the system going.”38 The Kodak system founders on “human unpredictability,” but “human judgment,” the root of that unpredictability, is Kodak’s only bulwark against the system exceeding their instrumental needs and becoming a talent-churning end in itself.

“Some Observations…” approaches without ever explicitly stating the crucial distinction: that between specific corporate interests, and the hermetic efficiency-drive of the systems they employ. The report thus centralizes a passing warning in the “inefficiency” speech about “systems” that “no corporate product planning can control”: optimizing systemic efficiency serves no-one unless human judgment keeps the system tooled to a particular human goal. Suppressed throughout his ventriloquous speeches, eliminated from the prose of J R, human judgment’s value here comes to the fore. For all that the language of “failure” takes a human subject or adjective wherever it recurs throughout this short report, this is one document in which Gaddis carved out a space in which thought and psychological categories could retain practical value.

Gaddis’ corporate environment often conflated human judgment with human unpredictability as a single enemy, treating supra-human “efficiency” as a natural and sufficient goal. His own corporate work consistently warns against this conflation, but in J R’s world and form it has become the problem-generating default. The same goes for another of the corporate work’s warnings: that “management” might become an essentially machinic rather than critical discipline: not a collaboration of human beings deciding on ends and means through the medium of social human judgment, but merely a structure for the top-down promulgation of anti-human efficiency. On the latter model, management must tailor the world to fit what it can process, not only responding to customers but constructing them: “The measure of marketing’s success lies in its ability to recognize, and even create, potential market situations.”39 J R represents a world that has taken this logic to its extreme, in which nothing can be “recognized” that hasn’t first been “created” in management’s, or (for Recktall Brown) “Business”’ own image.

When a system becomes an end in itself, postponing its own degradation requires a degradation of human inputs. A system that “depends heavily on impartiality in handling, in order to remain intact” can only process things intelligible in impartial terms.40 The work of keeping the system running degrades judgment by leaving its operators in “no substantial position to discriminate effectively among the demands placed on its services.”41 In this respect, the humans who ought to control and make “demands” on the system actually end up serving it by going out of their way to pre-sort, forestall, and hollow out “unreasonable” human inputs. “Some Observations…”’ warnings against conflating managerial work with efficiency-maximizing surely animate J R’s constant use of a similar pattern: JR’s insistence that Bast legally change his name to Edwerd so as to ratify a misprinted batch of business cards; PR man Davidoff’s circulation of press releases about events that have to be brought about by the people reading them; JR’s convincing himself that his fabricated corporate bio-blurb really does make him a “man of vision” characterized by an “austere, indrawn indwellingness” (650);42 and most conspicuously, as I’ll discuss later, the school staff’s attempts—through that corporate-work register of “tailoring”—to get children to match pre-punched personality-template cards.43

J R eliminates transcriptions of human psychology just as the corporate work warns that a misguided equivalence between management and system-serving might come to eliminate the real thing. But where Johnston, LeClair, or Clune claim that J R is a norm-neutral novel of systems rather than of anachronistic psychology, “Some Observations…” recuperates “human judgment” as a value despite bringing it up as a problem. Gaddis suggests that eliminating the friction of human psychology from corporate systems is not only unwise but technically impossible. Kodak can’t flatten the inputs or smooth the system beyond a certain point, since wherever human brains persist, there has to remain a distinction between immediate sorting and the “time and other pressures involved in decision making…”44 J R’s supra-intentional flatness and flow represent a world that has ignored this warning, hence Angela Allan’s reading of that world as “the disastrous fantasy of neoliberalism.”45 And, as Allan suggests, the novel examines what happens when that fantasy encounters persistent human realities.46 The “decision making” necessary for dealing with unpredictable humanity is itself work that needs “time” and human effort, and Gaddis here defends what he had been asked to overcome: the ineliminable complications of mental work against outsiders’ presumptions of, and systems’ expanding demands for, simplicity and simplification.47

Even in the “seek the inefficiency” speech, human unpredictability is valuable for offering occasions for judgment, since “[w]ithout the stimulus of that sovereign individual, the customer at the point of sale—there wouldn’t be any reason for change. And planning is change.”48 In defending change-responsiveness, “judgment,” “planning,” and “decision,” “Some Observations…” attaches value to the other “unreasonable” psychological categories that Gaddis’ default corporate discourse sought to eliminate. J R, I’ll show, isn’t just mimicry of the world that attacks these categories, but pursues “Some Observations…”’ defence of them. Ideas worked out in the corporate writing establish both the novel’s central problematic and the terms of its stylistic defaults. J R represents a world in which the identification between “management” and the judgment-free system blindly maximizing efficiency at the expense of the human has come to pass. And as Gaddis clarifies in “Some Observations…” that world isn’t essentially flat, but actively flattened by a particular corporate mindset. “Some Observations” gives us a context within which to understand J R’s flatness/flow axis as contingent, interested, constructed, and resistable.

**

J R’s central friction-problem is what place and value might persist for friction in a world and style that seem to have done away with it. My focus on recuperation requires both sentence-level analysis of how J R creates specific local effects, and an attention to shifts in these modes across the course of the novel. My subsequent approach thus departs from the critics I’ve discussed above who, for all their differences, share a tendency to treat J R’s 726 pages as embodying a single “form,” about whose implications they talk more in general than through comparative passage-analyses.49 The specifics of Gaddis’ corporate work, I hope to show, don’t just illuminate J R’s broadest rhetorical methods, but also the sheer variety of sentence-level modes by which he, within those broader constraints, conveys argument.

In the two sections that follow, I analyse corporate-work/novel connections that show how the forms of Gaddis’ corporate work help J R—within stylistic terms initially given over to flatness and flow—find stylistic ways to represent achievements of friction. In the paper’s final section, I show how these achievements finally exceed the stylistic to generate narrative events and an optimistic overall rhetoric.

J R: A Slideshow Novel?

Many critics treat J R’s removal of conventional psychological transcription as rejecting not only the conception of subjectivity associated with the traditional novel, but the novel form itself: instead, it’s “something more like a film or a play,” a “transcribed acoustic collage,” an interrogation of the concept of “voice” through plays on audio recording technology, or a “telephonic satire” in which crossed wires are the narrative analogue.50 The corporate work gives us historical warrant for seeing J R—particularly its alternations of visually-driven narration and the flow of dialogue—in terms of another format: the slideshow.

Gaddis himself stressed J R’s formal connection to cinema, but even in a letter discussing a potential film adaption had nothing to say about the visual aspects of its narrative style:

I think that in its departures from conventional fiction techniques the novel J R is essentially cinematic […] the absence of the author/narrator in my effort to make it all ‘happen’, to make the story tell itself in scenes cutting one into another uninterrupted by chapter breaks; absence of subjective characters, interior monologues, no “he wondered,” “she felt…”, “he wished…” &c; as little description and narrative as possible beyond what the reader sees and hears from the characters themselves.51

J R’s narrative sections often present us images outside the eyeline of “the characters themselves,” and the specifically visual nature of so much of Gaddis’ corporate work, which critics have barely acknowledged,52 offers more help than this letter in explaining the workings of the narration’s visuality. His earliest work on a visual project was a script for an army film about the battle of St. Vith, a script one viewer found “poetic,” like “something left over from The Recognitions […] Actually, a reading of the narrative leaves one with a distinct impression of overwriting, but when the narration is put with those grim shots of violence, it all smooths out.”53 Gaddis wasn’t responsible for shooting those “grim shots,” and it’s unclear whether he had any role in the editing that “put” them “with” his words.54 But his increasing responsibility for the visual directions of his slideshows and film scripts eventually earned him paid work in “editorial and visual consultation,” or even just “visuals.”55 How, then, did he get from scripts unfavourably compared to his first novel to developing a distinctive visual-direction style that anticipates important aspects of his second?

Two otherwise contrasting critics identify elements of J R’s narration that, when combined, help explain its slideshow quality. For Chénetier, the narrative passages underlie the dialogue, “structur[ing] a vision, establishing long distance iconic isotopes that contrast with the merely obsessive rehashed quality of reported speech.”56 As slideshows offer static images under linear speech, Chénetier reads J R’s narrative voice as establishing a bedrock world of “quiddity” over which its dialogue merely washes, generating an overall rhetoric of discoverable depth.57 Levine’s account of narration-dialogue interaction, by contrast, emphasizes disconnection, alternation and flatness: J R’s dialogue is “a soundtrack in progress without a picture on the screen,” its narrator-passages correspondingly a “film in progress with the sound momentarily turned off.”58 Levine’s flattening of the narrative voice to “a mechanically produced impression of what lies on the surface of the scene” is belied by the very passages he cites,59 but he does, with more linguistic precision than Chénetier attempts, highlight one crucial stylistic element: “Although [one passage] refers to a number of specific actions, assigning any one of them a specific temporal duration is difficult, mainly because of the frequent use of gerundives and the word ‘as’.”60 In other words, the J R narrator most often presents actions through continuous-tense verbs, something native to the slideshow medium, whose static images can only ever present actions in process. This core vocabulary of gerundive verbs and the simultaneity-markers “as” and “while” matches the visual directions Gaddis wrote in his corporate work.

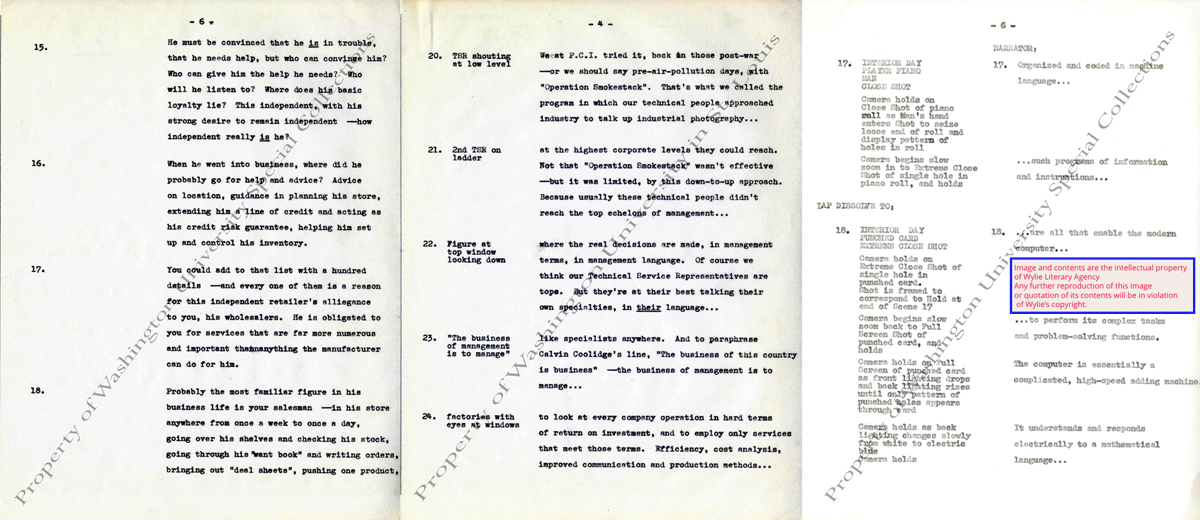

Gaddis’ growing compositional responsibility for those directions can be traced across the three chronologically ordered documents below (see Figure 2):61

The first pair are the first and the penultimate presented versions of the same long-toured speech on management/technician relations at Kodak.62 Gaddis initially just broke a pre-written script into slide-numbered chunks of similar lengths without visual directions.63 A Quiz script written for IBM around the same time seems to be where Gaddis first wrote basic directions, suggesting for example that one question be asked “over a visually dramatic sequence of a glass manufacturing operation in France, featuring the positioning of patterns into which the glass will be cut.”64 “Visually dramatic” is telling not showing, but in later iterations of “A Better Way,” Gaddis had become fluent in creating drama through visual sequencing, composing directly for the capabilities of the slideshow format.

The visual directions accompanying each slide in the final version use verbs only in those present-continuous forms—“shouting,” “looking”—that Levine finds distinctive to J R’s narration.65 The images Gaddis specifies don’t just illustrate the words of the script, but follow a narrative logic of their own, directing the viewer’s visual attention between characters and perspectives, up and down the levels of a building analogized to a corporation. In his first version, each chunk ended on a sentence break, but here slide-changes happen in the middle of sentences, with words and images conditioning each other differently from slide to slide. If the slideshow format’s basic logic is firstly that one image illustrate each chunk of content, one chunk explain each image, and secondly that one element remain stable while the other shifts, then Gaddis’ work in the format is notable for how flexibly it makes varied significance out of each transition.

In the page I reproduce from the penultimate “Better Way” script, for example, slide 20’s illustration of a technician shouting upward is only explained in the final words of its script, whose sentence then runs on to slide 21, whose image of a ladder immediately illustrates the same sentence’s concluding mention of the attempt to reach” “highest corporate levels.”66 Slide 21’s own final half-sentence, about the “top echelons of management,” seems to develop the same ladder-image, but the transition to Slide 22 reveals that the full sentence has completely changed the narrative perspective: the image of a management “figure looking down” matches the sentence’s new alignment of “we” with those “top echelons,” turning the “Technical Service Representative” whose upward-shouting perspective slide 20 had called “our” into a “they” now invisible to the audience but not to the figure looking down.67 Slide 23 abandons visual narrative to project the moral of this shift, taking three sentences of framing script to build up to the words it reiterates. Slide 24, meanwhile, returns to imagery without returning to narrative, using “eyes at windows” to show how literally “to look” is the defining verb of slide 23’s stipulation of management’s duty “to manage.”68 More than mere illustration, language and image interact flexibly throughout the script to complex argumentative ends – clarifying structures of mutual perception within corporate structures, or developing “management” from a single survey-perspective to a disembodied panoptical scrutiny.69

Gaddis’ later, less frequent work in film screenplay, meanwhile, draws distinctively on his slideshow expertise, as in the third image above (taken from a rejected IBM film script on “Software”).70 Throughout this script, cinematic composition is a lot like slideshow composition, with “camera holds” being the most frequent instruction, and an emphasis on slow zooms and slow changes of lighting that correspond to the brief narrations that accompany them.71 In place of -ing verbs, Gaddis composes his continous zooms and holds through simple-present verbs like “holds,” “enters,” “drops,” “rises,” and “changes”: the action-in-process here is often that of the camera itself, the visual directions conveying a constant overlap and simultaneity through the repetition of those temporal markers “as” and “while.”72 Actions overlay actions, which overlay camera movements, which overlay the narration. Words and images regulate, drag, and impel each other: a more flexible, interchangeable, in Chénetier’s word “labile” version of his bedrock/overflow account of the word/image interaction in J R.73 Consequently, the interaction is capable of more precise local rhetorical effects than either Levine’s or Chénetier’s monolithic accounts of flat disconnection or persistent depth will allow.

The formal specifics of Gaddis’ corporate visual composition serve its arguments in complex, almost allegorical ways that J R goes on to refine. Indeed, notes toward J R were written on the back of off-printed corporate-work slideshow scripts.74 This relationship makes sense when we appreciate how directly the concerns of these particular scripts match the novel’s,75 and how often too, at Kodak in particular, Gaddis was writing self-consciously about visual technology’s capacity to provide insight into processes corporate and suprahuman.76 This self-consciousness about his medium led him quickly to narrative proficiency in it, making the motion from slide to slide or the fitting of sentences to zooms and holds and fades tell stories, develop concepts, in content-bearing ways beyond the capacity of language alone. Matching the slideshow work’s flexibility, J R interweaves narration and dialogue differently from scene to scene and sentence to sentence, with a variety of rhetorical implications. As I’ll now show through analyses of specific examples, these are often legible in the terms of flatness and depth, flow and friction, that I’ve already suggested link corporate work and novel.

**

The early scene from which I draw my examples—in which Bast returns to his aunts’ house to find that the outbuilding where he does his composition work has been broken into, and then explores it with his cousin Stella—is one that Tabbi discusses in stylistic and visual-media terms, stressing the degree to which perceiving consciousness saturates the prose as “[w]e follow Stella’s flashlight the way our eyes might follow a panning camera in a film.”77 Like Levine and Chénetier, though, he doesn’t examine how narration and dialogue interact, and as I’ll show, it’s in that interaction’s service of thematic argument that the influence of Gaddis’ slideshow career is most obvious.

The scene introduces Bast with a moment of formal self-consciousness that complicates the usual relationship between a visual tableau and explanatory language; his aunts’ dialogue constructs him as spectacle before his own visual perceptions saturate the narrative language with conceptual content:

—Oh, it’s Edward?

—Edward… but what’s that he’s carrying?

—It looks like a can.

—A beer can!

—In the living room? What in the world!

—You, we said he was upset Stella, but…

—If he could see himself…

But only the wallpaper’s patient design responded to his obedient query, glancing from habit to an unfaded square of wall where no mirror had hung in some year. —It’s empty… he brandished the can, —I just thought I’d… (67).

In slideshow terms, the dialogue builds a seemingly uncomplicated tableau of Bast in the act of “carrying.”78 But the narrative sentence that follows the aunts’ incomplete conditional “if he could see himself…” dissolves indicative description; the grammatically intuitive referents of “glancing” and “empty” (the design and the square) both have to be cancelled and reinscribed (as Bast’s action and the can’s state). Narration and dialogue pull against each other, reflecting Bast’s own awkward formal role in the scene: both the object of perception and a saturating perceiver. “Habit” frames Bast’s actions as separable from self-perception and depth-psychology, and the passage’s verbs, as the wallpaper “respond”s to his “query”ing glance (itself an “obedient” response to non-imperative dialogue) seem to render him a passive rather than sovereign actor. But his uncompleted “I just thought” raises the competing possibility that the narrative passage preceding it constitutes an act of reflective thinking. The conceptual content of that narration—which offers Chénetier-approved intimations of worldly solidity in the wallpaper’s “unfaded” “patience”—may be either Bast’s or the narrator’s, an ambiguity that establishes the subsequent scene’s concern with perceptual reflexivity and the origins and force of conceptual thought.

In Bast and Stella’s subsequent investigation of the outbuilding, by contrast, narration and dialogue untangle themselves, impelling each other into an unbroken flow, taking it in turns to generate narrative events:

She thrust a thigh against the heavy door pushing it in on its hinges, shoving the neatly broken pane with a thrust of her elbow, crushing glass underfoot with her entrance, asking —is there a light? And as surely finding the switch, dropping the heavy shadows of overhead beams down upon them, bringing the brooding outdoors in, paused, as he came up short behind her, apparently indifferent to the lingering collision of his free hand in its glide over the cleft from one swell to the other brushing up her waist to the elbow, where only the tremor of uncertainty in his grasp moved her on into the vacant confines of the room to murmur —it needs airing… (68–9).

Here, dialogue-tags remove the earlier passage’s perplexities, narrative sentences incorporate dialogue, narrated actions answer vocalized questions. Yet a counterpoint to this flow persists in the contrast between two types of continuous action. Stella’s single-action verbs like “asking,” finding,” “dropping,” and “bringing” move the narrative onward, but against a backdrop of impersonal nouns “brooding” and “lingering.” These set her actions against suprahuman timeframes—arboreal when discussing the “lowering threat” trees pose to the front windows, diurnal in the invocation of “brooding night”. “Lingering” even renders a “collision” static, as only still image would usually have the power to do. “Scantling,” a paragraph later, takes these long-durée continuous verbs to their logical conclusion: a former gerund so permanent it has lost its root verb in becoming a noun. These slow backdrop verbs pull against Stella’s “thrust,” “pushing” and “crunching” as the previous scene set Bast against his aunts’ dialogue. His “uncertainty” here matches narratorial reservations like “apparently” and “as though,” establishing that Bast’s perceptions are the root of the narration’s vocabulary, and hence that the long-durée continuous verbs and the earlier passage’s “patience” characterize him in opposition to instrumental talk and fluent action. This aligns him with the depth-implications of supra-human time against the flatter prose of Stella’s “sure” action. These narrative passages thus offer depth not just as Chénetier’s bedrock beneath the dialogue, but as stylistic repository for Bast’s unvocalized “thought.” Such thought thus retains textual space even within formal principles that notionally deny it, retains space even in the narration of apparent aimlessness, passivity, and diffident “habit.”

The narrative voice’s backdrop work becomes more self-conscious when the pair reach Bast’s music room, where the continuous verbforms apply not to the visible, physical world, but to music’s power to condition whatever it underlies. Bast and Stella converse over “strings forboding” on a “turning record”:

—Is this F-sharp? She ran a finger along the stave, bent closer, struck it turning him on his heel as her left hand rose to bracket C two octaves down in tremolo.

—No wait what are you…

—All the spirit deeply dawning in, is this what you’re working on?

—It’s no it’s nothing! He pulled the pages from the rack —it’s just, it’s nothing… and left her standing, the strings patterning their descent in the slope of her shoulders to remain there, as she bent to close the keyboard, in the remnant of a shrug (69).

As the passage begins with the record’s “turning,” so it ends by emphasizing that music’s “patterning” of the scene’s various components.79 When Stella leaves the outbuilding a page later, before Bast turns off the record player, the analogy between visual and musical backdrop-conditioning of dialogue and events becomes even more explicit: “She brushed past him for the door where the strings rose again, gaily framing an empty trap in the eaves beyond” (71). In “patterning” and “framing,” the scene’s slideshow verbs now describe their own narrative function. The “framing” initially seems to be the action of the most recent noun, the strings, but the sentence’s development clarifies that it refers to Stella’s shape from Bast’s visual perspective. Until this misdirection, the passage’s continuous tense stems only from the music, over whose backdrop the scene’s action and emotion run like slideshow speech. And the music bears grammatical agency for the scene’s tendency to stillness: it’s what “remain[s] there” in Stella’s body, “left… standing” in a continuous whose root verb is already slideshow-static.80

This achievement of stillness makes ever more explicit the essentially allegorical relationship between Stella and Bast. To put it simply, Stella is stylistically tagged with flatness and flow, Bast first with the depth beyond the flatness, and then with the frictive slowing of that flow. Take the scene’s most direct contrast of verbs: Stella’s “turning” Bast with a single note conjures that “obedient” reflexive form of agency with which he began the scene, but the “turning” record finally stills Stella herself. Bast’s thought and compositional work are associated with the way the backdrop “turning” comes to constrain Stella to its rhythm. As his perceptions in the preceding passage established the slower backdrop temporality that the turning record later embodies, it’s no coincidence that the words she reads from his work in progress involve “spirit deeply dawning”: a phrase that yokes together the non-material, the scene’s intimations of depth, and a verb with both supra-human-timeframe and mental-process connotations. Bast’s composition expresses his aspiration to precisely what the “turning” record achieves: the creation of an artwork that can transmit depth and pace alternative to the Stella/JR world.

These stylistically allegorical interactions persist until the scene is bookended by another empty can. At the railway station on her way home, Stella meets Bast’s fellow flow-threatened protagonist Gibbs, with whom she once had a relationship. Their dialogue is almost uninterrupted by narration, but plays out over backdrop continuous verbs from the passage in which Gibbs is introduced:

The platform shuddered with a train going though in the wrong direction and a tremor lingered on her frame, turning away, following its lights receding as though desperate to lose distinction among lights signifying nothing but motion, movement itself stilled by distance spreading to overwhelm the eye with the vacancy of punctuation on a wordless page. She reached an empty trash bin and dropped the can clattering into it… (73–4).

As with Bast’s aunts, Stella’s dialogue imposes visual narration on Gibbs, who’s “wandering round a train platform with your old books and papers, your hair messed and you, a hole in your trouser seat you look…” (74). But the setting’s own verbs of long duration—“lingered,” “following,” “receding”—develop Gibbs’ “wandering” less in the urgent indicative terms of Stella’s questioning—“How did you end up in a place like this?” “What are you doing here! What are you doing in a town like this…” (72)—than as a slow zoom deeper and deeper into the “vacancy” of the transit-setting that wandering has brought him to. Even though dialogue and narration are kept maximally separate in this scene, the backdrop verbs stress the dialogue’s “empty” energy, as Stella’s questions that don’t wait for answers embody the “clattering” end-in-itself imperative of “nothing but motion.”

Against this, the narrative voice develops Gibbs’ perceptions beyond Stella in far more pessimistic terms than Bast’s: what we get here is not “deeply” and not “patterning,” but a mere “distance spreading to overwhelm the eye.” If Bast’s perceptions posited an alternative to Stella’s thoughtless urgency that eventually had the power to “still” her, Gibbs’ perceptions are inseparable from the motion they oppose, as the ambiguous agent of “spreading,” which might be either movement or stillness, makes clear. Gibbs’ perception of “distance” is essentially flattening: it serves “vacancy” and the “empty,” unlike Bast’s connection to “depth,” which takes the narrative voice in the outbuilding scene far beyond the “empty” “can” with which the dialogue begins it. Gibbs’ free-indirect narrative-voice perceptions, unlike Bast’s, find no way to intrude into the dialogue to which they provide a backdrop. The narration he saturates provides only the sense of hopeless, directionless drifting that that dialogue exacerbates. These stylistic differences of perceptual framing set up the fact that it’s later Bast, not Gibbs, who is finally able to achieve some compositional work.

These four passages from a single scene show how flexibly Gaddis interweaves dialogue and narration for distinct reading experiences and thematic effects. They show how the basic principles of continuous-tense tableau-establishment and the slow-zooming implication of simultaneity through “as” and “while” connect the formal mechanics of J R to techniques of visual rhetoric that Gaddis developed over the course of his corporate slideshow work. And they show how some of the content-bearing visual storytelling techniques he developed there allowed him to make essentially allegorical currency out of conflicting narrative paces:81 the sentence-level modulations in dialogue/narration interaction render Gibbs and Bast’s relations to Stella legible in terms of friction and flow. Gaddis’ major development of slideshow logic for J R is—as unites all this scene’s variety—to make the idea of dialogue running over a visual or musical backdrop a principle by which that backdrop’s consciousness can propound another temporality, a frictive drag of experience or value that suggests that being, in Karl’s terms, “caught in… what the flow determines” is not a done deal.

The slideshow, then, is a more capacious and archivally warranted way of thinking about interactions between the visual, the narratorial, and the vocal in J R than previous critics’ efforts to tag narration and dialogue with stably separate implications allowed. The corporate work lets us read the variety of their interactions from scene to scene as a source of formal rhetoric. It is similarly helpful for understanding how Gaddis created meaning and addressed matters of what I’ll call “ideological friction” within the novel’s reported speech alone.

Authorial Implication and Ideological Friction within J R’s Dialogue Forms

However they disagree on the role of the narrative sections, Levine and Chénetier concur that the novel’s flow of dialogue is “flat” – incapable of bearing authorial implication beyond the immediate communicative or instrumental intent of the characters who speak it. Yet J R’s dialogue, just like its interactions with the narration, is internally organized in a variety of content-bearing ways.

Tabbi, attentive to Gaddis’ “textual exposition” of systemically-constrained layers of cognition, notes how J R conveys narrative information through novel-wide echoes: “Next to the first-order (mis)communication among characters, the narrator in J R achieves a kind of second-order communication unavailable to the characters—but available to the attentive reader who is willing to enter into this second-order conversation.”82 David Letzler too sees J R’s formal organization in terms of information-extraction, as a “rigorous test… of readers’ high-level attention modulation,” honing their ability to parse out “text of genuine importance” from “within an avalanche of cruft.”83 Letzler’s reading requires significant text and redundant cruft to be semantically similar, but much of the implication within J R’s dialogue emerges from its foregrounding of linguistic difference, especially of puns and ambiguities unintended by their speakers. “Import” for both Tabbi and Letzler means information about narrative events, but Gaddis’ repertoire of intra-dialogic constructions creates “second-order” conceptual and thematic meaning above and beyond either characters’ “first-order” communicative intentions, or information about fictive facts.

Such second-order implication’s suggestion of underlying orchestration interrupts the dialogue’s putatively author-independent flow, its pretensions to mere transcription. Semantic depths and ideological frictions grow within the very style ostensibly optimized to flatness and flow. As I’ll show, Gaddis’ corporate work had trained him in the elimination of such depths and frictions, and the four basic forms of intra-dialogue implication that I’ll discuss are thus legible as reversals of the corporate work’s polarity, restoring communicable communicative friction to a world that sought to eliminate it.

The simplest of J R’s flow-interrupting moments of implication come when the novel cues us to treat any of its interrupted sentences as completed by that interruption. A routine business conversation between lawyer Beamish and PR man Davidoff, for example, leads to the following confusion:

get this grant out so there’s no legal snag in the Foundation’s tax exempt status when he goes into it for a loan to Virginia told you to get Moyst…

—Moist?

—Moyst Colonel Moyst told you to get him on the phone” (525).

The pun that makes “get Moyst” a lewd imperative has little thematic significance.84 What’s important is the shift in spelling: “Moist” and “Moyst” are rendered as the character intends, rather than for auditory difference. The pun’s emergence from miscommunication overcomes the speaker’s intent, suggesting that external arrangement can always generate second-order meanings out of language that aspires to be self-contained or purely instrumental. That outward productivity of exceeded intent is the basic premise for the more complex examples that follow.

Perhaps the most frequent of these generative arrangements is counterpoint, in which mutually oblivious speakers cast mutual light intended by neither. Gaddis literalizes that situation in the early scene where school administrators and corporate sponsors discuss the funding of their closed-circuit TV infrastructure, and then their music education program, while watching Bast’s disintegrating onscreen Mozart lecture (typographical difference reinforces the two speeches’ separation):

Of course we have you foundation people to thank…

—Rich people who commissioned work from artists and gave them money (40).

[…]

just in music alone we’re already spending on band uniforms alone…

—three more piano concertos, two string quartets and the three finest operas ever written, and he’s desperate, under-nourished, exhausted, frantic about money… (41).

These ostensibly simultaneous and overlapping discourses create a single verbal string intelligible in terms of the novel’s concern with the relation between artistic composition and finance. This orchestration points us to a composer, Gaddis, beyond the speakers. The control-room dialogue reveals how Bast’s patronage problems exceed even those that he laments on Mozart’s behalf: the classroom “work” that his “rich people” commission is not the artwork for which he wants to use their money. Unlike Mozart’s patrons, they are indifferent to whether or not he creates; they just require him to recite.85 Their repetition of “alone,” meanwhile, emphasizes the separation between their and Bast’s understanding of “music”: for him a compositional practice and communicative experience, for them a discrete budget category.86 This infrastructural separation of artist from art means that it’s not Bast who gets to say the word “music,” and just as the administrative sentence starts with that word but moves on to fripperies, Bast’s own sentences begin with “artists” and specific forms of artwork, but run through negative mental states to end at their cause: “money.” These authorially-orchestrated echoes and parallels develop a critical, historical account of the money-art relation, but unknown to the speakers who, “alone,” lack the perspective to develop it.

If those two modes of implication create supplemental meaning out of the forward-tumbling overlap between speakers, then Gaddis also makes significance out of the solecism and stumbling within speech. Malapropisms, for example, often restore second-order communication to instrumental jargon. See, for example, the late scene where JR asks Bast to marry the daughter of an executive to help him regain some boardroom control:

they got this gossip calumnist to like fix you up with her hey Bast?… she’s this whole heiress of these two hundred shares of Diamond Cable hey Bast? Where she gets these rights to them once you marry her to vote them when we make this here tender offer hey? Then you get this divorce just like everybody… (657).

If the pun in “gossip calumnist” is self-explanatory cynicism, then that in “tender offer” is more thematically salient. Its technical meaning is the price a company’s owners offer shareholders for a buyout. But here it’s an accidental travesty of the actions and emotions involved in a marriage proposal: JR’s vision hollows such human relations out to a repertoire of contractual moves. “Tender offer” specifically reduces affective human negotiations to a model predicated on conglomerate audiences and market determinations of worth. The pun highlights how a world like J R’s makes the technical meaning more first-order intuitive to a child than the affective. Here, then, Gaddis uses dialogue alone to achieve the kind of revivification of dead language that Chénetier had thought restricted to the narration.

Beyond malapropisms and travesty, Gaddis makes thematically salient wordplay out of even the stutters and stumblings that ought most clearly to embody Letzler’s irrelevant “cruft.” Take, for example, the passage in which headmaster Whiteback tries to explain how the school’s personality-testing will match each child to an existing set of punch-cards:

“this equipment item is justified when we testor tailing, tailor testing to the norm, and […] the only way we can establish this norm, in terms of this ongoing situation that is to say, is by the testing itself” (22).

Whiteback’s initial stumble, his “testor(ed) tailing,” flips phonemes just as his testing flips the sequence of norm, data and subject.87 Even more than the travesty of “tender offer,” this articulates J R’s central structural principle, matching up with cart-before-horse promulgations of bureaucratic norm throughout the novel, as press-releases precede and dictate events, misspelled business cards require legal name-changes, and so on. Testored Tailing, in other words, specifies in J R the worldview Gaddis had, in identical terms, warned against in “Some Observations…”: a system that has overridden regulatory “human judgment” “demands orders tailored to… itself.” Gaddis’s corporate work—even pre-dating “Some Observations…”88—worked out the basic structure, and vocabulary, for J R’s critique of an administered society.

J R, through Whiteback, renders Gaddis’ corporate-work warnings about skewing the input to the filter as stylistic comedy. And this comes at the novel’s outset; Whiteback’s worldview is a given, not a pending threat. His seemingly incidental spoonerism epitomizes Gaddis’ stylistic mimesis of how administrative capitalism’s worldview actively limits permissible inputs and hence constructs the world it claims only to reflect or enable.89 Testored Tailing is the managerialist flow against which J R seeks ways to restore friction, and its clearest formulation in the novel comes through wordplay rather than narrative event.

What the four examples I’ve discussed have in common is their making supplemental, salient meaning out of apparent flatness or “cruft.” The elements that have led so many critics to figure J R’s dialogue as vacuous—its constant interruption, overlap, malapropism, stumbling—all serve at times to create semantic content rather than, in Letzler’s word, dissolving it. Gaddis’s fractured dialogue isn’t just a device for dispersing information about narrative events, but develops moments of seeming disintegration into some of the novel’s most important argument.90

Though most critics treat J R’s dialogue as undifferentiated semantic flatness and uniform chronological flow, the structures by which Gaddis makes meaning within it reveal potential depth—in Chénetier’s sense of authorial conspicuousness and meaning-generative capacity—and potential friction too. As I’ve examined in both narration and dialogue, the novel’s sentences constantly seem set to mean one thing before the next word forces a reintegration of the whole, often by re-prioritizing secondary or tertiary meanings of words. This makes those hinge-words conspicuous within Letzler’s “avalanche,” interrupting its monolithic flow by forcing us to check, think, re-process. As Tabbi’s stress on supra-intentional meaning suggests, this interferes precisely with the promulgation of Testored Tailing by individual agents: defying first-order speech goals, these moments highlight internal frictions and contradictions within the ideology’s top-down dialogic flow. The organizing principles of systems aren’t objectively assessable by the agents who comprise the systems, on Tabbi’s reading: only from a reader’s perspective, with Letzler’s trained attention, are these frictions legible. But legible they are, and further framed as exploitable. The stylistic innovations I’ve examined clarify that the flattening instrumental speech of Testored Tailing harbours—in language’s systematic capacity to exceed speakers’ reductive efforts with counter- or supra-intentional meaning—the resources for its own obstruction.

These moments, then, are vehicles for what I’ll call ideological friction.91 They restore the possibility of competing meanings and perspectives to a world whose initial conditions seemed to eliminate these as anachronisms. This dynamic is another legacy of Gaddis’ corporate writing.

**

“Ideological friction” is a trope warranted by the way so much of Gaddis’ corporate work required him to assemble ideologically “smooth” and coherent documents out of an array of contradictory source materials pushed on him by institutional agents with competing interests. J R’s stylistic moves restore to its world the kind of friction and depth that Gaddis’ corporate work had trained him in eliminating, as in one of his earliest assignments for IBM—a 1963 brochure on their educational investment policies. The archive preserves three full and two partial drafts, which let us trace the eliminations step by step.

This was technically an internal document, but produced explicitly in order to be able to show to national audiences.92 The sources and ongoing feedback Gaddis was asked to synthesize were correspondingly incompatible, but all leave identifiable traces in his final draft. His basic problem was the need to balance “public relations dividends”93 with explicit discussion of how education funding served the “development” of IBM “resources.”94 Should “IBM” and “industry” be the agentive protagonists of the brochure, or should they appear only in service to “Education” and “society”? While his early drafts preserved overt conflict between industry and culture at the sentence level, the final version coherently subordinated them. His phrasing—for example on “American industry’s permanent obligation to education, as the source of its own talent and vitality”95—stresses an “obligation to education,” but leaves industry the basic value.96 Meanwhile, he dealt with IBM’s cutting down on PR-friendly “unrestricted” grants97—as their “contribution philosophy” “matur[ed] from one of ‘charity by reaction’ to one of ‘investment by direction’”98—by reframing the term to apply not to IBM’s money but to their abstract commitments, as in “unrestricted basic research with guaranteed freedom of inquiry…”99 He also resolved his supervisors’ contradictory advice about how to frame IBM’s decreasing funding to the humanities. After initial imperatives to stress funding for maths, science, and management training, the addition of a new supervisor after the first draft saw Gaddis suddenly asked to stress IBM’s commitment to humanistic education as a response to the space race, which demanded a reassertion of the difference between technologist communism and the “pluralist” “wide-ranging and free mind of the well-educated American.”100 Gaddis dealt with this by playing up IBM’s increased funding for mathematical study as an increase in commitment to the liberal arts, none of which beyond maths got a mention.101

The clearest example of Gaddis’ competence in the smoothing of ideological friction, however, comes on a topic where he made changes himself without top-down prompting. One supervisor wanted him to publicize IBM’s work on “projects to facilitate adjustment to automation.”102 Gaddis thus developed it into a significant theme in his first full draft, tying it closely to discussions of “human resources” and training future workers. The conflict between automation and the “human” led early drafts into philosophical confusions, which Gaddis’ notes suggest he was aware of. This was as ever a matter of the sources he was trying to reconcile. In documents for IBM audiences, the field of automation offers only “exciting prospects,” its fresh achievements are “newsworthy.”103 But in the public-facing sources, automation is a pending mystery that always collocates with “social change.”104 His initial-draft rhetoric was more in line with public worry than IBM celebration: treating automation as a “challenge” with unpredictable “ramifications” of which “the public becomes more aware,” and above all as a “problem” next to which IBM’s unspecified “positive solution”s seemed pretty unpersuasive.105 Where IBM had wanted the topic stressed in order to emphasize their interest in getting schoolchildren exposed early, Gaddis’s initial draft took a wider perspective on living “in a period of accelerating change,” anticipating J R’s concern with unrestricted expansion and things ramifying faster than the initiators can control.106

The subsequent first submitted draft removes all the wavering: Gaddis mentions automation only once, discussing IBM’s role in “a special teaching unit and film strip to familiarize junior high school students with computers and automation.”107 Automation here is no longer a contested novelty: it’s a given, to which kindly IBM helps the world get “familiarized.” Gaddis’ initial attempts to juggle the attitudes handed down to him produced something morally ambivalent, but the latter draft removes the moral question. He replaced most mentions of the abstract process of “automation” with emphasis on the content of classes about “science and technology.” Rather than problems of “adapting” to automation, he focuses on “revising career guidance services and educational approaches in the light of technological advance,” “advance” connoting a positivity and control absent from his initial focus on “accelerating change.”108 Gaddis made these changes before he got any external feedback, and the topic of automation required no explicit revisions in his final draft. Even on this very early project Gaddis could do the work of removing ideological friction and flattening competing discourses unprompted. This was true even when the very frictions he was removing were those he would later foreground in J R.

The crucial revelation here, then, is that the corporate work didn’t just give Gaddis a jargon to work with, but taught him exactly what that jargon was concealing and how because it was so often he who had to conceal it. The flat language of systemic business in J R is, as Gaddis knew from experience, a strenuously repressive construction, not just an emergent “postmodern” condition. Writing J R as a critique of the mindset he’d learned to work in, he could simply reverse the polarities and restore the ambivalences. He could highlight the ineliminable ideological faultlines within a discourse designed to deny them. If “Some Observations…” was Gaddis’ clearest first-person engagement with friction-problems and the limits of a testored-tailing mindset, his ventriloquous and anonymous documents gave him a training in removing ideological friction and veiling the language of bad faith, corporate self-interest, and straightforward hypocrisy. This helped him write a novel that mimics the smooth flatness and flow of those documents while consistently drawing judgmental attention to the ambivalences that they strove to elide. Once again, the practicalities of the corporate work help us understand the rhetorical resources of the fictive style.

On this reading of Gaddis’ “technical training,” he didn’t just recapitulate his corporate work through mimicry, but inverted it from the inside, finding ways to represent achievements of friction and its potentially paradigm-resistant work that, as I’ll show, finally move outward from language to affect the events of the novel’s narrative.

Style Guide ≠ Rhetoric Guide

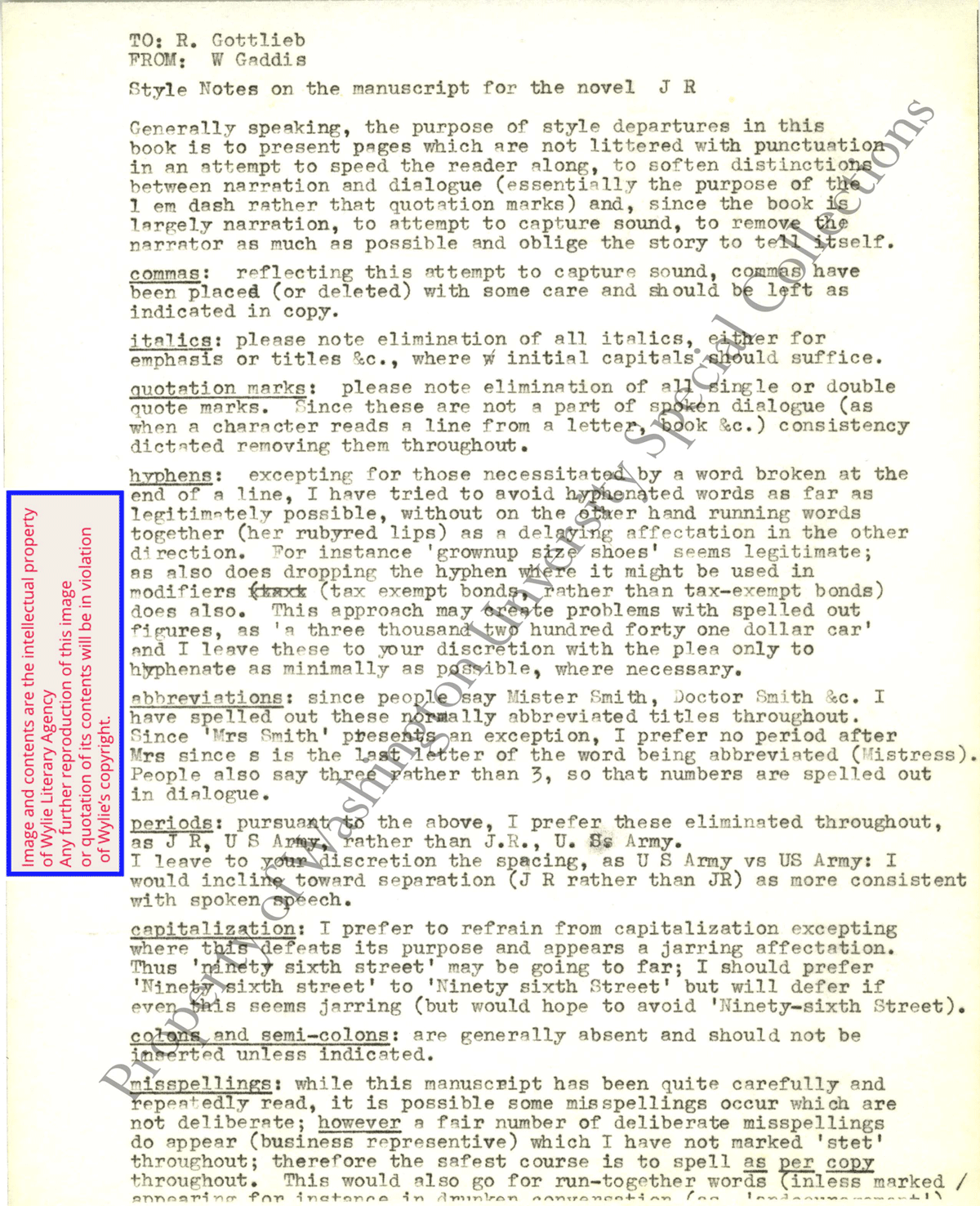

John Johnston argues that “J R intends neither compensation nor redemption; it is simply a demonstration, in the most rigorous terms imaginable, of one aspect of the ‘postmodern condition’ in which we now live.”109 Such purely mimetic approaches insist on a narrative as well as a stylistic flatness: J R can’t develop any perspective beyond the flatness and flow that characterize its basic form. The way it initially frames its world must be its entire rhetoric. Yet as I’ll show, major narrative developments—like the collapse of JR’s empire, Bast’s success and Gibbs’ failures in composition, or the switching relation to friction in Bast’s relationship to J R—correspond to stylistic modulations. A “demonstration” reading can’t attach rhetorical significance to these developments.110 Before I examine how the “redemptive” friction-reading I’ve derived from the corporate-work/novel relation migrates from the stylistic to the narrative, I’ll address the archive’s strongest support for a rhetorical-flatness approach: Gaddis’ “Style Notes on the Manuscript for the Novel J R,” which Sonia Johnson uncovered and discussed for 2012’s social media reading event “Occupy Gaddis” (See Figure 3).111

Gaddis tells his editor that J R’s distinguishing “style departures” function to

“present pages which are not littered with punctuation in an attempt to speed the reader along, to soften distinctions between narration and dialogue (essentially the purpose of the l em dash rather than quotation marks) and, since the book is largely narration, to attempt to capture sound, to remove the narrator as much as possible and to oblige the story to tell itself.”112

Though he doesn’t use the word itself, as he would in his later Paris Review interview,113 it’s clear that Gaddis’ stipulations focus almost entirely on generating the mimetic experience of “flow.”114 Removing obstacles to the inner ear and to the eye on the page, he aimed to create a textual world that would “sweep along” his readers as the dialogue of others so often sweeps Bast, Gibbs, or the lawyer Beaton, highlighting the struggle of what Karl called a “life outside what the flow determines.” Explicitly constructing flow, these notes make no mention of depth, of friction, of development: of anything, that is, that would suggest Gaddis’ stylistic departures left space for the representation of resistance.

It would be a mistake, though, to take these notes—which set out the overall grammar of the novel much like a newspaper’s style guide sets out its conventions of punctuation, abbreviation, and citation—as a guide to what the novel does within the terms of those conventions. For that very reason, it clarifies that the stylistic and narrative givens of J R’s world make a fait accompli of the eliminative efficiency-dream of “smooth” flatness and flow Gaddis warned against throughout his corporate career. The “Style Notes” show Gaddis excising forms of on-page friction to establish flow as the novel’s formal dominant. They don’t, however, tell us whether or how the novel goes about putting that dominant in question. Concerned only with the experience of eyes processing the page, this document addresses systems-thinking or economic postmodernity as little as it addresses friction or resistance. Its remit is narrow. “Style” here is a matter of removals,115 and the notes tell us nothing about interpretation or construal. As a guide for someone preparing the book, not for someone reading it, it offers little insight about rhetorical implication.116 Its separation from the kind of style-centric reading I’ve offered of specific passages reflects its separation from the question of the novel’s rhetorical development: this is what makes it a style-guide rather than a reading-guide.

If it takes a reader only a few pages to get to grips with the stylistic givens established by “Style Notes…,” then I don’t read the subsequent 700 as “flat” reiteration of those givens. I’ll show finally how the stylistic rhetoric I’ve derived from the corporate work’s correspondences with the novel—J R’s sentence-level resources for recuperating “human judgment,” resistant meaning, and ideological friction—influences events and the narrative’s overall shape. In Johnston’s terms, J R is precisely interested in the “redemption” of written-off human categories rather than mere “rigorous” “demonstration” of a supra-human “now,” and that redemption happens, eventually, in narrative action as well as stylistic implication.

Style, Events, and J R’s Rhetorical Arc

To understand the axis of style and narrative on which Bast and JR’s exchange of relations to friction takes place, we need to understand language’s role in the Testored Tailing that links the novel’s form to the corporate work’s insights. The corporate work insists on this connection, from defining “improved communication” in anti-judgment managerial terms in “A Better Way,” to echoing Agapē Agape’s preoccupation with the limits of “machine capabilities” in the late IBM software film’s discussion of “a language suited to the machine’s limited capabilities… which will enable it to function.”117 The models of efficiency promulgated in such work require that the psychological depths “in which decisions are made” conform to “management terms… management language.”118

If Testored Tailing is Gaddis’ stylistic rendering of how his characters get “conditioned” for “machine capabilities,” then he makes clear that “management,” its “terms,” and its “language” are active agents of that conditioning. J R, like the corporate work, frames the flattening flow of Testored Tailing as intentional, top-down, directed, and uni-directional.119 Consequently, the way aspects of language are transmitted from person to person tells us both how the system works, and where those “ideological friction” breakdowns can be identified and exploited.

Testored Tailing is not just a quirk of Whiteback’s personality and language: its top-down intentionality becomes clear as the novel gradually reveals more information about his place, as school principal, in a chain of command down which language and ideology flow. Below him, administering the punchcards that will set the norms, is school psychologist Dan DiCephalis, below whom, reading classroom scripts, are teachers like Bast and Gibbs. Immediately above Whiteback is Major Hyde, a military man employed by a subsidiary of Typhon International, the over-arching corporation run by Governor Cates, a politician and businessman who inspires JR early on in the novel. Cates is the clearest linguistic embodiment of the “management” ideology in the novel, the character whose speech most clearly folds decision and action into a single flow of performative sorting that can act in the world without recourse to unspoken deliberative depths, as in this passage in which he trouble-shoots issues raised by the lawyer Beaton:

First thing I want cleaned up’s these damned mining claims Beaton get Frank Black’s office find out if they’re worth the damn paper they’re written on this outfit’s in there on mineral exploration just to cut timber get hold of Monty, Interior serve them with an injunction maybe they’ll be ready to do business, when Broos calls get him onto that old sheep state… (433).

This flow of instrumental talk is the norm to which the rest of the world must be tailored: a norm transmitted to schoolchildren through Bast’s script, delivered to him by DiCephalis, who’s supervised by Whiteback, who’s employed by Hyde, who’s controlled through a variety of corporate functionaries who answer to Cates, whose corporation includes the manufacturers of the school’s TV equipment.120